I’m visiting all 600 L.A. spots on the National Register. Here are 10 you can’t miss

- Share via

I’m not a marathon runner. My bucket list mostly includes breweries and taco spots I haven’t tried. My calendar is rarely booked much more than a few weeks out, unless there’s a big metal show coming up. Point is: I’m not the kind of person you’d expect to commit to visiting 600 L.A. landmarks on the National Register of Historic Places. Yet here I am, with a blog and an Instagram account dedicated to this quixotic project.

How did I end up here? It’s September 2021, midpandemic. It’s year two of working remote, and I’m going stir-crazy from all this aimless … sitting I’ve been doing. So I decide to take a bike ride to this extravagant shrine at the cemetery next to the Burbank Airport. You know, the one with the scale model of the Columbia space shuttle mounted in front of it? Turns out, the structure has a fascinating history involving Burbank’s long involvement with the aviation industry, Churrigueresque-style architecture and D.W. Griffith’s infamous film “Intolerance.”

Planning your weekend?

Stay up to date on the best things to do, see and eat in L.A.

While I was reading about the shrine, officially called the Portal of the Folded Wings Shrine to Aviation, I noticed that it was on the National Register, a list of places across the country that are deemed significant by the National Park Service. If a lifelong Angeleno like me had never heard of this spot before, how many more landmarks must be hiding in plain sight?

Visiting that shrine flipped a switch in me. I used to spend most of my free time at record stores. Now I go to house museums and take photographs of 1920s bungalow courts. It’s kept me connected with my city during the pandemic, reignited my interest in architecture and introduced me to people and neighborhoods I didn’t know existed. It’s also been a great source of adventures for my family. While my 6-year-old daughter may not share my newfound love for clinker-brick retaining walls, she did make up a killer National Register theme song at the top of Angels Flight Railway.

So far I’ve visited 174 of the nearly 600 National Register sites in LA. Here are 10 that are well worth visiting, all for very different reasons.

One important PSA: Several of the below sites are private residences. So if you gawk, please respect the stewards of these historic homes and gawk from the sidewalk. Let’s not break any trespassing laws, mmkay? Happy landmarking.

Lummis Home (El Alisal)

Lummis built his home by hand over a period of 15 years, with the help of a constant stream of Indigenous kids from the Isleta Pueblo in New Mexico. The floors are all concrete so that they could be easily hosed down after one of the endless parties that Lummis threw at the house (he called them “noises”). Wander around the bountiful gardens and imagine what it must have been like to spend time here before the 110 Freeway was constructed, just steps away.

And did you know this? Embedded into the window frame in the living room are negatives from photographs that Lummis took during his travels around the Southwest.

Admission: The Lummis Home is open for free, self-guided tours from 10 a.m to 3 p.m. Saturday and Sunday. Docents from the Los Angeles Department of Recreation and Parks are usually there to answer questions.

Frank Lloyd Wright's Ennis, Freeman, Millard and Storer houses

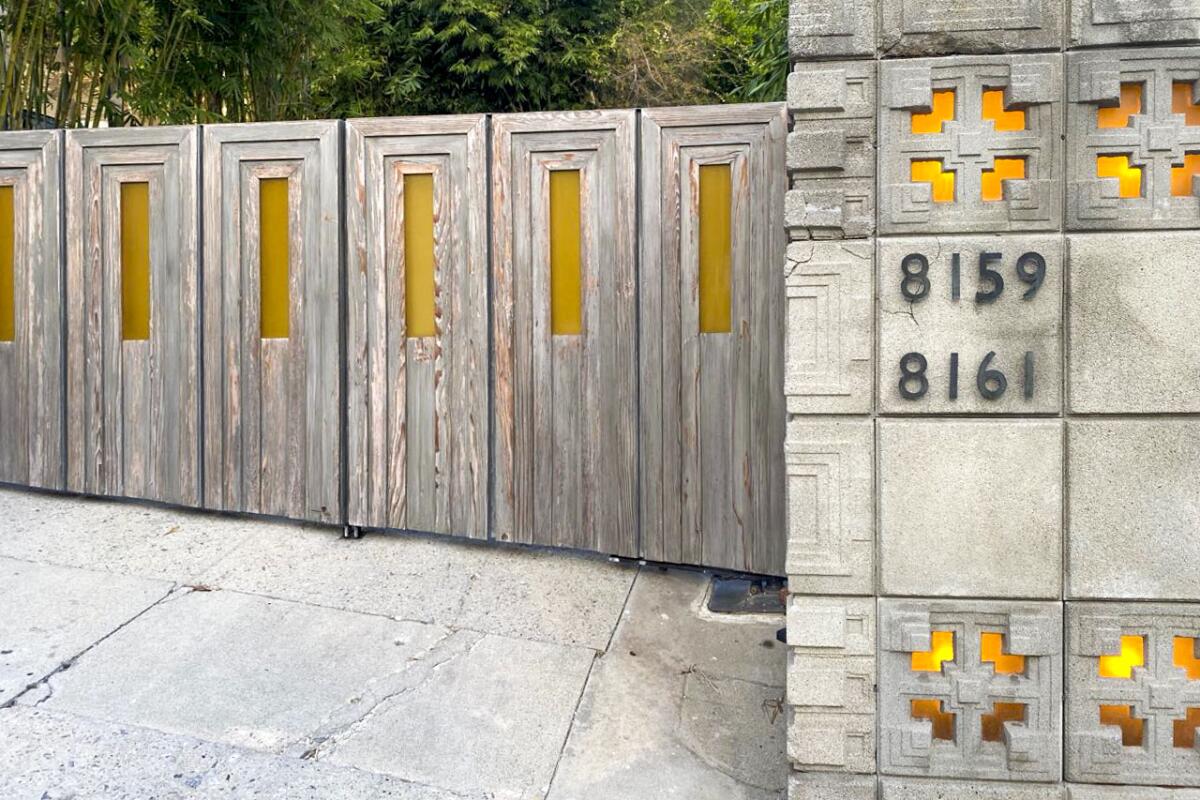

Though built of similar materials, these houses have distinct personalities. The Ennis is an imposing hilltop fortress with a Hollywood pedigree (“Bladerunner,” “The House on Haunted Hill,” etc.); the Storer is the sleek cliffside villa; the Millard is the lush jungle dwelling, especially as seen from the back gate. After decades of decay, the Freeman is just beginning a restoration by its new owner. They’re all worth visiting to see how Wright applied his ideas in different settings.

The marker on the map takes you to the Ennis House. Other addresses: Freeman House, 1962 Glencoe Way, Los Angeles; Millard House, 645 Prospect Crescent, Pasadena; and Storer House, 8161 Hollywood Blvd., Los Angeles. These houses are all privately owned. The Ennis offers periodic tours (visit ennishouse.com); when restored, the Freeman will occasionally open to the public as a condition of its easement with the L.A. Conservancy.

Did you know? Frank Lloyd Wright’s son, Lloyd Wright, was construction supervisor on all four houses and designed a detached studio for the Millard. Famed architects Rudolph Schindler, John Lautner and Gregory Ain all worked on the Freeman at various points.

Vasquez Rocks

Did you know? The Vasquez Rocks’ alien topography has made them a popular backdrop for film and TV shoots since the early days of Hollywood — most famously in the O.G. “Star Trek” series, also in “The Ten Commandments,” “The Muppet Movie,” “Blazing Saddles” and music videos by Radiohead, Rihanna and BTS.

La Laguna de San Gabriel

Did you know? La Laguna is a great example of community preservation efforts in action. When it faced demolition in 2006, a group of locals formed Friends of La Laguna to save it. They’ve since raised some $700,000 to restore and preserve the playground, piece by piece.

Park Place/Arroyo Terrace Historic District

In addition to the seven Greene & Greenes, you’ll find an English Tudor-style home designed by Pasadenan Sylvanus Marston (also known for the Fenyes Estate and the USC Pacific Asia Museum), and a lovely Colonial Revival joint by Myron Hunt (Rose Bowl, Huntington Library).

Contributing houses are on 368-440 Arroyo Terrace; 200-240 Grand Ave.; and 201-239 N. Orange Grove Blvd., Pasadena. All homes are privately owned but viewable from the street. Gamble House docents offer a regular Greene & Greene Neighborhood Walking Tour of the Arroyo Terrace neighborhood.

Did you know? This district includes homes that architects Charles Greene and Myron Hunt designed for themselves.

The Old Mill (El Molino Viejo)

For seven years, the mill provided food and resources to the mission, but it was abandoned when a more efficient mill was built not far away. Edward Kewen, first attorney general of California, lived here from 1859 to 1879. Then the Huntingtons came-a-buying in 1903 and converted it into a clubhouse for the golf course attached to their hotel. In the 1960s, Leslie Huntington Brehm willed the Old Mill to San Marino. It’s now operated by the nonprofit Old Mill Foundation, which keeps a small interpretive museum downstairs and hosts rotating art exhibits by the California Art Club upstairs. The landscaping is gorgeous too.

The Old Mill building is open 11 a.m. to 2 p.m. Tuesday through Sunday. Garden hours are 9 a.m. to 4 p.m. on those days.Closed onholidays. Admission is free.

Did you know? For decades the original millstones were thought lost, until a young George S. Patton rediscovered them on the grounds of the Huntington Library, years before his military career. They’re currently enjoying their retirement on the patio, as we all should.

27th Street Historic District

The 27th Street Historic District also offers an important reminder that well-designed, charming homes aren’t the exclusive province of the wealthy. Developed between 1895 and 1926, these houses were built for working-class folk, in all the favored styles of the day. You’ll see Queen Anne Victorians with gingerbread ornamentation; transitional Craftsmans, sheathed in clapboard; even a couple Colonial Revivals with porticos and Grecian columns.

Visiting the district: The 27th Street Historic District centers around the intersection of East 27th Street and Paloma Avenue. Some contributing buildings are further south on Paloma Avenue and east of Paloma on East 28th Street. The houses are privately owned and not open to the public. The 28th Street YMCA is now an apartment building offering affordable and transitional housing.

Did you know? The most significant building in this district is the 28th Street YMCA. This stately Spanish Colonial looker was designed in 1926 by Paul Revere Williams, the first Black American with an architecture license west of the Mississippi. Williams later designed private mansions for Hollywood’s elite, but early on he had a major impact on the built world of the Black community in L.A.

Angels Flight Railway

In 1996, a restored Angels Flight opened up just south of its old home, connecting California Plaza on Grand Avenue with the commercial corridor on Hill Street. There have been bumps on the track, including a 2001 accident that killed a tourist and a derailment in 2013 that led to a four-year closure. However, it’s been a smooth ride since Angels Flight reopened in 2017.

You can access Angels Flight from the Top Station at California Plaza (shown on this map) or the Lower Station (351 S. Hill Street, Los Angeles). It’s open every day from 6:45 a.m. to 10 p.m., including weekends and holidays. Fares are $1 each way, or $2 for a souvenir round-trip ticket.

Did you know? The Angels Flight cars are named Sinai and Olivet, after biblical hills. These same two cars have been in use since 1905.

Mission San Fernando Rey de España

Of course there was also a dark side to the mission enterprise. Franciscan priests brought thousands of Chumash, Tongva and Tataviam people here, often against their will, to be Christianized and acculturated, and to work on the vast farms and ranches owned by the missions. To its credit, the Catholic church has set up a museum in the convento, documenting the difficult daily lives of the natives who lived here.

This is a peaceful place of worship, a vitally important link to Los Angeles history and a site of deracination and enslavement. That complex, uncomfortable legacy is all the more reason to see it for yourself.

Did you know? The San Fernando Mission Cemetery is the final resting place for Bob Hope, Ritchie Valens, Ed Begley and many more.

Rockhaven Sanitarium

Rockhaven was one of the first American institutions run by and for women. Richards also embraced the novel idea that physical environment shapes behavior. She built a facility that felt serene and human in scale, full of single-story cottages, beautiful landscaping and meandering walkways to encourage her ladies to stay active.

Rockhaven closed in 2006 and was bought by the City of Glendale. In 2021, State Sen. Anthony Portantino secured $8 million to preserve it and turn it into a museum. Maybe by its 101st anniversary?

Did you know? Rockhaven’s residents included actress Billie Burke (Glinda the Good Witch in “The Wizard of Oz”) and Gladys Baker Eley, mother of Marilyn Monroe.