As his daughter lay in a pool of blood in an El Paso Walmart, a pastor held fast to his faith

- Share via

EL PASO — The pastor had never prayed so fervently.

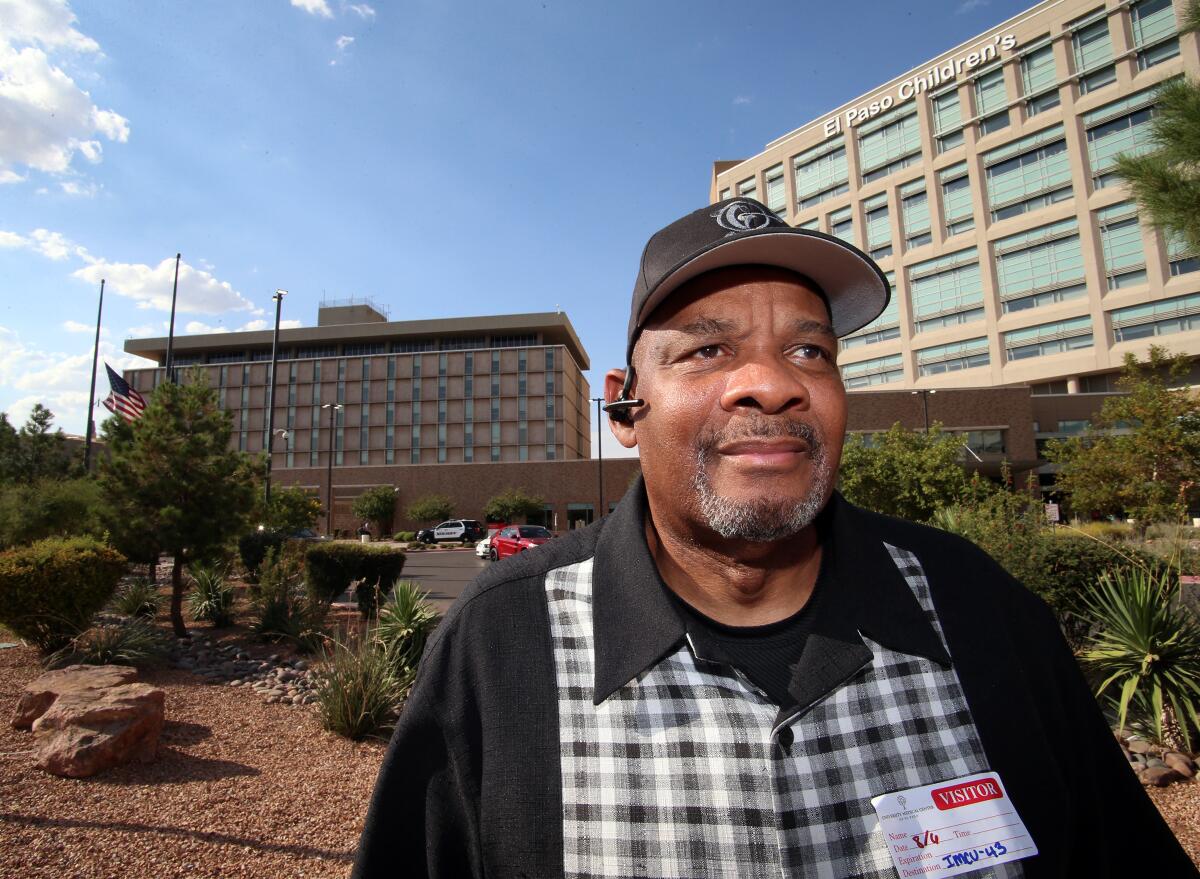

Michael Grady had just learned that his 33-year-old daughter was lying in a pool of blood at Walmart.

Shot three times, Michelle Grady had managed to dial her cellphone to call her mother, Jeneverlyn, who jumped in her car and kept her on the line until she reached the store.

His wife called him from the store, and Michael Grady raced to join them. The drive from his house to the Walmart normally takes about seven minutes. It felt longer.

When he finally arrived, the parking lot was already taped off. He saw his wife’s car by the theater next to the store. He parked. He ran.

But his 65-year-old body, which had endured a quadruple-bypass heart surgery a few years prior, couldn’t move nearly as fast as he would’ve liked.

Grady prayed.

“I was asking God to make sure Michelle isn’t in a lot of pain or was suffering,” he said. “That we would get through to her and find her. That was my prayer.”

When he saw her, it was bad. “I know she wasn’t OK, but I told her she was going to be OK.”

It wasn’t a lie. It was hope. The pastor doesn’t believe God fulfills prayer requests like Santa Claus.

There weren’t enough stretchers to move her out, so Grady and his wife lifted her body onto a Walmart shopping cart used for oversized items and wheeled her out to an ambulance.

They waited. Time felt both stretched and condensed. Things needed to move faster, Grady thought. After an emergency crew got Michelle into an ambulance, his wife rode with her. He ran — chest heaving — back to the car, then sped toward University Medical Center of El Paso.

The emergency room doctor told the pastor and his wife and two other daughters that a bullet had entered her right thigh and cracked her pelvis. Her middle finger had nearly been blown off. Her intestines were a mess.

He heard the words the doctor was telling him about his daughter — the one he called “Do-Wop” because she was short and always looked up to him — but understood only one thing: It was really bad.

They told him she needed surgery. Probably more than one. There were no guarantees. He prayed for the doctors to have wisdom. He prayed for courage for his daughter, himself and his family — no matter the outcome. He prayed for the families of the other victims.

Grady, a burly man with a deep voice, knew plenty about death. He’d buried a sister, two brothers and his mother.

When he was 17, he worked in a funeral home and had planned to become a mortician. But a few years later, the funeral home burned down, and he was out of a job. It was 1974 and he wasn’t entirely sure what he would do. He’d been preaching since he was 12 and thought maybe that would be his path.

Then one day he was walking home when he saw a military recruiting station. The U.S. Army was the first counter he saw and the man asked him if he’d like to travel. Grady said he didn’t even have a car. Besides, he figured on being a preacher. The recruiter told him he could be a chaplain.

He joined.

Grady was newly married and he and his wife were stationed in Greece, Italy, Turkey and Germany. Several spots in the United States too. They had three daughters and a son. He counseled veterans — people who had seen friends die. People who had seen marriages break up. People in despair asking him where God was when their tragedy hit.

Now he was sitting in the waiting room of a hospital, wondering whether he was going to lose his daughter.

“I wouldn’t try to make excuses for God,” he said. “God has a purpose, even in this. And he stands with you, and the people of God stand with you to cover you with love and grace and walk with you on this journey. It says ‘walk through the valley of the shadow of death,’ not ‘stop in the valley of the shadow of death.’”

The doctors came out of the surgery late in the afternoon Saturday and said her vitals were stable, but she’d need another surgery on Sunday.

The fears incited by the weekend’s shootings in El Paso and Dayton are still on the surface for many. Amid heightened fears, security experts debate protecting ‘soft targets’

Grady is pastor of Prince of Peace Christian Fellowship — a yellow-tan building less than 10 minutes from where the shooting occurred. With about 45 congregants, he needed to make sure the church was open. An assistant volunteered to preach for him.

On a normal Sunday, his daughters — including Michelle — would arrive a little after 10 a.m. and start warming up as a part of the church’s praise and worship team. Grady would prepare his sermon.

By 12:30 p.m., his wife and daughters would’ve left to go to his house for their weekly dinner. He would be the last to leave. “It’s not a megachurch, so I have to lock up,” he said.

Grady said they’d eat and play games. One Michelle mastered involved listening to loud music through headphones and reading lips. He can beat her at dominoes, though.

But this Sunday he was sitting in the hospital. By that afternoon, the doctors told Grady and his family that surgery had been successful. It was unclear if she’d keep her finger, though.

She remained heavily sedated, but when her family walked into the room, she blinked. The family prayed in her room.

El Paso, a mostly Latino and Democratic city, has long viewed Trump warily — and his most forceful statement since the massacre did little to change that.

On Monday, Grady was at the hospital when the breathing tube was removed. Michelle was hoarse and couldn’t speak. She was able to motion with her hands a little. He was grateful for that small gesture.

While Grady took a short break in a waiting room, his phone kept ringing. His friend, U.S. Rep. Veronica Escobar, whose district includes much of El Paso, and who the black pastor had worked with in El Paso on civil rights, called to get an update. So did Army buddies from South Korea and Italy.

He was touched by the outpouring. But he wanted to get back up to the ICU to see his daughter. After more than two days there, he knew his way around the byzantine hallways of the hospital. Up the elevator. Past two sets of double doors. Beyond the table strewn with empty pizza boxes and a roomful of people who were also waiting. The nurses smiled or nodded as he walked by. Tragedy had bred familiarity.

He wasn’t sure what her first words would be when she was finally able to talk. He hoped for, “Hi, Mommy. Hi, Daddy.” His eyes welled with tears.

Grady peeked his head through the door and around the curtain. Michelle was crying.

“We’ve been with her ever since she was shot. We’ve been here every day,” he said outside her room. “And we will be here to try to dry the tears and let her know it will all be OK.”

He took a breath and walked in.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.