The rise and fall of Zimbabwe’s longtime leader: Robert Mugabe

- Share via

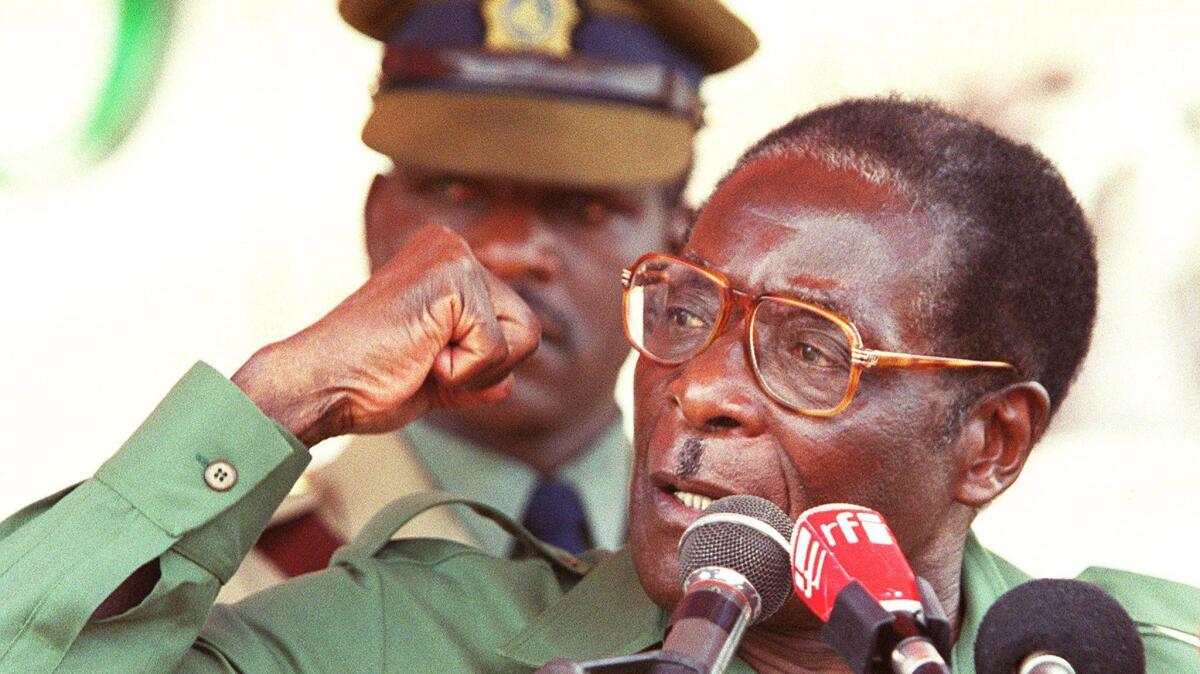

The rule of Robert Mugabe, a once-respected liberation leader turned feared dictator and international pariah, came to an unflattering end Tuesday when the Zimbabwean president was forced to relinquish his 37-year hold on power in the face of possible impeachment.

The future of the 93-year-old Mugabe, the world’s oldest head of state, now hangs in the balance. But his past paints a portrait of the disheartening decline of a man once viewed as one of Africa’s most promising statesmen.

Here’s a look at the life and legacy of Robert Mugabe:

He was born Robert Gabriel Mugabe in 1924 to a poor family in a town called Kutama in what was then known as Southern Rhodesia, a British colony.

Educated at Kutama College and at the University of Fort Hare in South Africa’s Eastern Cape, Mugabe studied history and English literature. He worked as a schoolteacher after graduating in the early 1950s.

Mugabe is said to have seven academic degrees covering a range of disciplines, including education and law, six of which were earned through correspondence courses and two earned while in prison for sedition against the colonial government, according to various news reports.

His early career as an educator took him to what was then Northern Rhodesia, now Zambia, where he worked at a teacher training college between 1955 and 1958, and then Ghana, where he undertook similar work. It was in Ghana where Mugabe met his first wife, Sally Hayfron, who died in 1992.

It was also in Ghana, the first African nation to gain independence from European colonialism, where Mugabe reportedly became inspired by African nationalism and Marxism.

In 1960, Mugabe returned to his home country, where his opposition to white minority rule exploded as he joined calls for independence and black-majority rule.

He embraced the Zimbabwe African National Union, later to become the Zimbabwe African National Union Patriotic Front, or ZANU-PF. His antigovernment rhetoric landed him in jail from late 1963 to 1974, after being convicted of sedition.

Once released, Mugabe fled to neighboring Mozambique from where he led a guerrilla war to end British rule. Defeat of the colonialists eventually came in a negotiated settlement. And in 1980, Mugabe defeated rival liberation leaders to become prime minister of the new Zimbabwe.

In a move to quash perceived dissent and consolidate power, Mugabe ordered a crackdown in the Matabeleland stronghold of his political rival, Joshua Nkomo, in which thousands of people were massacred.

As prime minister between 1980 and 1987, Mugabe called for national unity and preached racial reconciliation but his focus became the betterment of the country’s poor and downtrodden black majority. He introduced free education and healthcare, built new roads and opened the doors to black citizens in areas of business that were formerly reserved for whites.

Such policies won him praise as a father figure and a respected statesman, and he became a darling on the international stage.

But that would not last.

In 1987, Zimbabwe’s parliament rewrote the country’s independence constitution allowing Mugabe to become president shortly thereafter. The all-powerful position gave him the authority to dissolve parliament, institute martial law and run for as many terms as desired — essentially giving Mugabe the potential to become president for life, propped up by his ruling ZANU-PF party.

White parliamentary representation was abolished and the government was allowed to nominate 20% of the 120 members of parliament. Critics cringed that the country appeared to have created a monarchy.

In the early 1990s, the Zimbabwean government passed an amendment allowing the expropriation of about half of all white-owned land with the aim of resettling black families. The policy gained traction in the early 2000s, when Mugabe sanctioned the takeover of white-owned farms by veterans of the liberation struggle. The controversial plan met with backlash from the international community that threatened to withhold foreign aid to Zimbabwe and by white farmers who warned that appropriating their commercial farms would spell economic disaster.

Mugabe refused to abandon the plan and Zimbabwe’s economy soon began to tank.

The Zimbabwean dollar crashed, with inflation at one stage soaring to 500 billion percent. Unemployment skyrocketed, gasoline shortages became the norm and there were food riots.

With his political survival at stake, Mugabe turned to two main weapons: land and race.

Mugabe blamed white Zimbabweans and his political rivals, whom he accused of being colonial puppets, for the grinding poverty and financial free-fall. Critics said his government was largely to blame. Investigations by news outlets and civil rights groups found that some of the expropriated land was awarded to Mugabe’s ministers and cronies and not used to relieve the overcrowding of black citizens, who were crammed onto a tiny percentage of land.

The violence that erupted in the early 2000s when black liberation war veterans occupied and seized white-owned farms left scores dead, among them farmers, farm laborers and members of the political opposition.

In October 2000, efforts of opposition members of Zimbabwe’s parliament to impeach Mugabe failed. That same year, the country’s constitution was amended to force Britain to pay reparations for the land it had seized from blacks during colonial rule.

In 2002, the British Commonwealth suspended Zimbabwe from the intergovernmental organization made up mostly of former territories of the British Empire, and Zimbabwe withdrew the next year. The European Union imposed sanctions, such as a travel ban and the freezing of assets, on dozens of members of Zimbabwe’s leadership as punishment for not being allowed to observe the country’s 2002 presidential vote. The United States imposed similar restrictions.

Mugabe lost the first round of presidential elections in March 2008 to Morgan Tsvangirai, leader of the opposition Movement for Democratic Change, but the longtime leader would not cede power. Instead he launched a campaign of violence in which scores were killed. Tsvangirai ultimately withdrew from the second round of voting, but later agreed to a power sharing deal with Mugabe, and became the country’s prime minister. But by 2011, Tsvangirai declared the agreement a failure.

In 2013, Mugabe won another term in office amid widespread allegations of election fraud. By then, his second wife, Grace, a former state house typist he married in 1996 following an affair, had her eyes set on succeeding her increasingly frail husband.

That did not sit well with ruling party veterans of the liberation struggle, who turned on Mugabe.

The curtain began a fast fall on Mugabe’s reign when on Nov. 6 he fired his once-trusted deputy Emmerson Mnangagwa, who was considered Grace’s main rival to succeed Mugabe.

On Nov. 15, the military said it had taken control of the country, putting Mugabe and his wife in custody. Though urged to resign, the longtime leader continued to cling to power for almost a week — until Tuesday, when the threat of impeachment gave him little choice.

For more on global development news, see our Global Development Watch page, and follow me @AMSimmons1 on Twitter

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.