2017 was the year when North Korea became a threat to the U.S. mainland

- Share via

Reporting from Seoul — North Korea’s totalitarian leader, Kim Jong Un, began 2017 by announcing his intention to launch a long-range ballistic missile capable of reaching the United States.

The boast made headlines, but in one little noticed passage, the young leader Kim also admitted entering the year “anxious and remorseful” about his management.

“I am hardening my resolve to seek more tasks for the sake of the people this year and make redoubled, devoted efforts to this end,” said Kim, grandson of the country’s founder, Kim Il Sung.

As the year unfolded, Kim stuck to his resolution.

In 2017, Kim’s nation overcame technological hurdles to its long quest to build a modern nuclear weapons program, conducting a large underground detonation and test launching at least 17 ballistic missiles. All the while, Kim weathered international pressure and battled rhetorically with President Trump.

By year’s end, Kim had changed the threat perception in the United States and declared his nation close to having a “nuclear force,” a fact that would complicate efforts to confront his government.

“North Korea is no longer a threat [only] in its neighborhood,” said John Delury, an associate professor at Yonsei University in Seoul. “It now poses a threat to us, to the [U.S.] ‘homeland.’”

Following Kim’s speech, then President-elect Trump took notice, vowing that his administration wouldn’t allow the North to build an ICBM that could carry a warhead to the mainland. He tweeted: “It won’t happen!”

Kim remained mostly quiet for weeks. Then his military launched a solid-fuel missile, a significant milestone because such devices are easier to deploy and to conceal from enemies.

The following day, Kim Jong Nam, Kim Jong Un’s half brother, was assassinated at Kuala Lumpur airport, allegedly at the direction of North Korean agents.

Tensions began to rise and, as periodic reminders of the North’s illicit pursuit, the missiles continued to fly.

A month later, the North Koreans test-launched four at once, three of which traveled 600 miles into the Sea of Japan, also known as the East Sea, where many of its tests descend into the water. There were also public rocket engine tests.

It essentially ended debate about whether North Korea has the capability to deliver a nuclear weapon to the United States.

— David Wright of the Union of Concerned Scientists

Kim Jong Un’s scientists suffered setbacks, to be sure. At least four missiles exploded or fizzled shortly after launch during the spring. But while the missiles didn’t perform as planned, they delivered a message nonetheless.

A few launches appeared timed to coincide with key events. One came as President Trump was to meet with Chinese President Xi Jinping; another when Vice President Mike Pence was to arrive in South Korea.

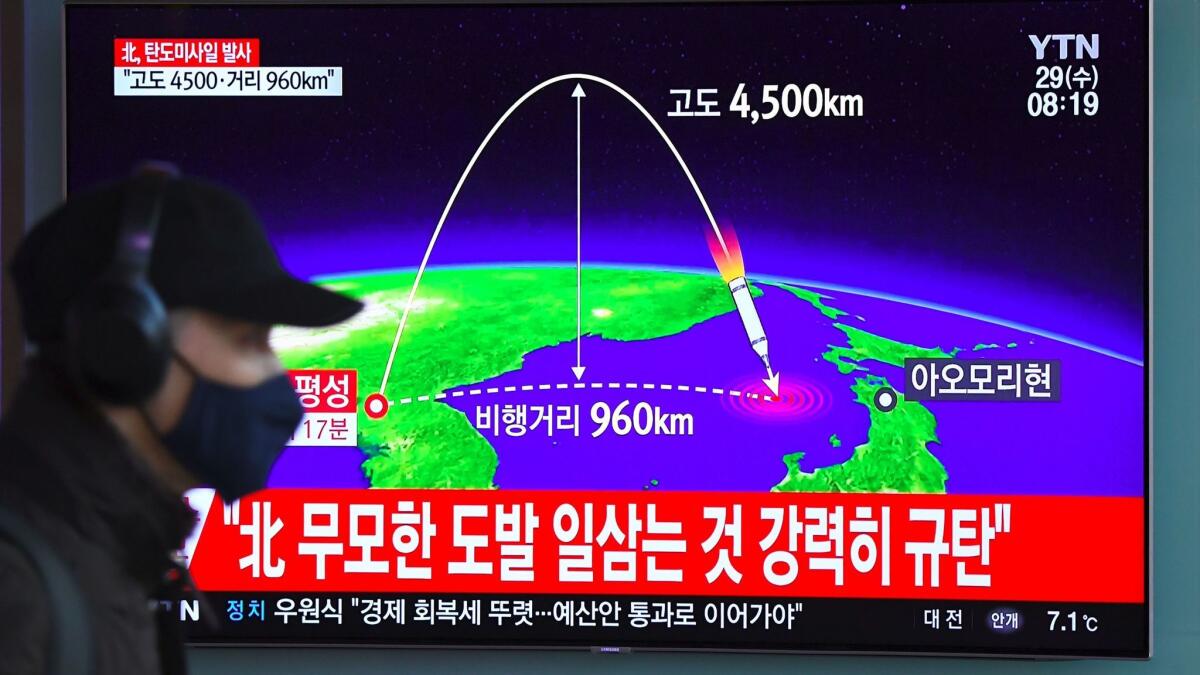

North Korea had a major breakthrough on July 4, another important date, launching its first intercontinental ballistic missile. It flew on a steep trajectory more than 1,700 miles into the space, for about 40 minutes, and landed in the waters east of the peninsula.

The accomplishment brought widespread concern and condemnation, but celebration by the North’s state media.

A few weeks later, the nation launched another ICBM that soared higher, flew longer and traveled farther. Experts believe that missile, on a flatter trajectory, could have reached Hawaii and Alaska.

This is when Trump and Kim started the rhetorical battle in earnest.

After the United Nations adopted a new round of economic sanctions in response to the tests, Trump boasted that the North might be met with “fire and fury.”

The North in turn suggested that it might target Guam, a United States territory in the Western Pacific, with an “encircling strike” to test its missiles.

This is perhaps when tensions were highest between the two countries, because North Korea made a direct threat to American national security, said Bong Youngshik, a research fellow with the Institute for North Korean Studies at Yonsei University in Seoul.

“The U.S. could have justified its military actions in response to the attack — had North Korea gone ahead — in the name of right to self-defense,” he said.

Guamanians braced for the worst, but Kim backed off the threat.

Meanwhile, the leaders kept trading taunts, and the North kept launching, including two tests over Japan that shocked leaders there.

The missiles fueled tensions all year, but it was the underground detonation of a hydrogen bomb in early September that could be Kim’s top achievement. Seismic tests backed the North’s contention that the device had “unprecedented power” compared with its previous efforts.

North Korean state television said the test was a “significant occasion” on its path to a state “nuclear force,” likely a reference to its desire to achieve military strength through modern nuclear capability.

Trump spoke to the United Nations not long after, saying he would “totally destroy” North Korea if it threatened the United States. Kim responded that “a frightened dog barks louder.” He also called Trump a “mentally deranged dotard.”

At times like these it seemed Kim and Trump were talking directly, albeit through the media.

Duyeon Kim, a visiting senior research fellow at the Korean Peninsula Future Forum in Seoul, said their exchanges were interesting but unfortunate. She would have preferred face-to-face talks between their two countries.

“The rhetorical battles were childish and unhelpful because they unnecessarily added to tensions,” she said.

Then, amid all the chatter, Kim Jong Un and his administration went largely quiet.

This pause in testing led some to hope that tensions might cool. Others believed the respite to be seasonal, not strategic.

The North refrained despite insults from Trump on Twitter, such as on Nov. 11: “Why would Kim Jong-un insult me by calling me ‘old,’ when I would NEVER call him ‘short and fat?’”

Then, in late November, the North Korean government launched its most-powerful intercontinental ballistic missile yet, a device capable of reaching Washington, D.C. The North said it flew with a heavy warhead to replicate a nuclear device, a hint that the nation was ready to cross Trump’s “won’t happen” red line.

“It essentially ended debate about whether North Korea has the capability to deliver a nuclear weapon to the United States,” said David Wright, co-director of the Global Security Program at the Union of Concerned Scientists.

At the end of the year, Kim’s “resolve” seemed as strong as ever, despite efforts by the Trump administration and other nations with an interest in curbing the North’s nuclear advancement.

In just the last few days, the North said relinquishing its nuclear weapons was a “pipe dream.” It said the latest United Nations sanctions, which cut fuel supplies, were “an act of war” violating its sovereignty.

After this year, Kim, who has long sought a nuclear armed missile as a deterrent, seems on an inevitable nuclear path that’s likely to shift the power dynamic in Asia.

“It was a great year for the Kim family’s regime security,” said Robert Kelly, a political science professor at Pusan National University. “The nukes now mean a United States attack on North Korea is extremely unlikely.”

Stiles is a special correspondent.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.