Her husband was killed in the Philippines drug war. No one would help her find answers

- Share via

Reporting from San Mateo, Philippines — Sheila Rivera’s nightmare began on June 20, when police burst into a subdivision and shot her husband to death. It continued when local officials refused to take her to his body, insisting that she go home and “get some rest.”

And it deepened when nobody — not even the wife of another man shot that night — agreed to support her quest for answers. Gradually, she began to feel that her country’s government, police and even the public were aligned against her — that if she wanted justice, she’d have to seek it alone.

“I knew that [the police] would just cover it up,” said Rivera, 31, speaking at her cramped home in San Mateo municipality near Manila. “And I’m still afraid we might get into trouble if we do something, if we ask too many questions.”

Although Belmonte was killed 10 days before Philippines President Rodrigo Duterte’s inauguration, the then-president elect had already urged police and members of the public to kill suspected drug dealers who resist arrest.

In the five weeks after he was elected on May 9, police shot and killed 40 suspected drug dealers, compared with 39 in the previous four months, National Police spokesman Wilben Mayor told Reuters.

I’m still afraid we might get into trouble if we do something, if we ask too many questions.

— Sheila Rivera

Since Duterte, 71, a tough-talking former mayor and prosecutor, took office on June 30, he has waged a brutal campaign against drugs and crime, vowing not to stop “until the last drug lord, the last financier and the last pusher have surrendered or put behind bars. Or below the ground if they so wish.”

His words have catalyzed a spike in extrajudicial killings. Approximately 1,800 suspected criminals have been slain since July 1, Philippine National Police Chief Ronald Dela Rosa announced on Monday -- 712 killed in police operations, and 1,067 by vigilantes. Few, if any, of the killings have been investigated, and many of the campaign’s victims and detractors have chosen to keep silent, bowed by a creeping climate of fear.

The families of victims have been “absolutely terrified into silence,” said Phelim Kine, a deputy director in Human Rights Watch’s Asia division. “There is such a daily deluge of horrific images of the victims of these killings, and a real sense of absolute impunity in terms of the perpetrators being brought to justice, that for many people, silence seems the safest and most prudent option.”

After United Nations human rights experts called on Duterte to stop the extrajudicial killings, the president threatened to pull the Philippines out of the U.N. “You know, United Nations, if you can say one bad thing about me, I can give you 10 [about you],” he said.

Duterte has rebuffed criticism of his campaign — he has repeatedly said that the police killings were lawful, as officers were acting in self-defense. He has denied allegations of involvement in vigilante killings.

And he has proven enormously popular, as many Filipinos see his strongman approach as a quick fix to the country’s long-running struggle with crime — he enjoys a 91% approval rating, according to the polling organization Pulse. Many of the country’s other top officials have scrambled to publicly endorse him.

On Aug. 16, Dela Rosa vowed to see Duterte’s campaign through to the end. “I will continue to motivate my men to exploit the momentum,” he said, according to the Philippine Inquirer. “The momentum is on our side. We don’t have to slow down.”

In a speech on Aug. 8, Manny Pacquiao, the Philippine senator and professional boxer, urged Congress to reinstate the death penalty in support of Duterte’s campaign. And at a press conference in July, the country’s Solicitor-General Jose Calida said that the killings have been “not enough.”

Meanwhile, many family members of victims, like Rivera, are left guessing about the reasons for their loved ones’ deaths.

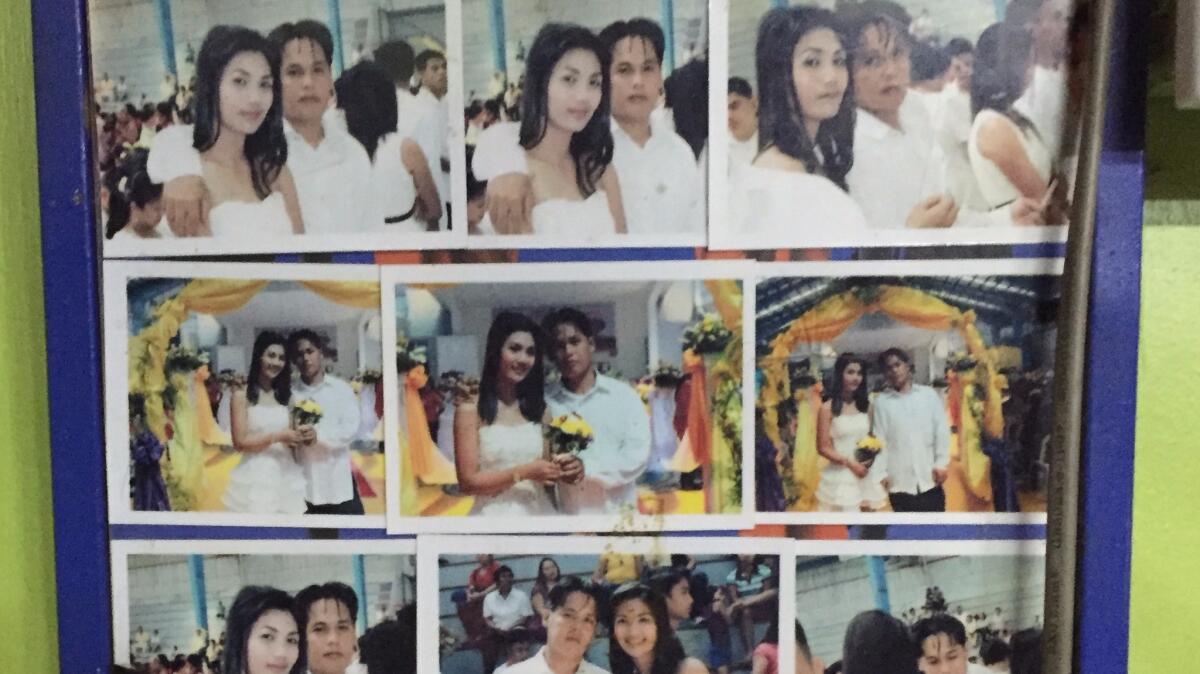

Letlet Belmonte, 31, was an auto-rickshaw driver with a passion for cooking, playing basketball, and breeding and racing doves, according to Rivera.

“We had a good marriage,” she said, as her 5-year-old daughter, Missy, nestled up against her, and her 9-year-old son, Reigan, looked on intently from across their tiny living room. “He was sweet and caring. He did everything for the family. And he was the one who cooked.”

Rivera, an unemployed former supermarket worker, said that Belmonte left the house at 8 p.m. on June 20 for his nightly shift on the auto-rickshaw. He usually came home by midnight, so when he hadn’t returned by 2 a.m., she went out to look for him. She noticed a “commotion” at a nearby subdivision — a line of auto-rickshaws, a throng of police — and then saw it: her husband’s auto-rickshaw, and a police officer pushing it away.

“I asked them where was the owner of the tricycle,” she recalled. “And they said that he’s not here now, he’s dead. A funeral parlor already has him.”

Local officials refused to take her to the funeral parlor, so she went home and flipped on the news. “I didn’t see him,” she said, “so I decided to go to the funeral parlor and check. Then I saw the body lying there, unclean, with gunshot wounds and covered in blood.”

Rivera says he never did drugs. She heard later from a local official that police had raided the subdivision seeking a suspected drug dealer. Belmonte was inside with six other people; police arrested four of them and shot three. Yet she still does not know what he was doing in the building, why he was shot, and specifically who shot him.

“There were killings, after the incident with Letlet,” she said. “Right after that, more killings happened in this area. I actually spoke with the wife of Roel, [another man who died in the shooting], and I encouraged her to speak [out] with me. And she was too afraid for her security.”

Amid the chorus of support for Duterte, dissenting voices have been few and far between.

Philippine Sen. Leila de Lima, a former justice secretary and perhaps the most high-profile critic of Duterte’s campaign, launched an official inquiry into the extrajudicial killings on Monday.

See the most-read stories in World News this hour »

“It’s pretty clear to me that these are state-inspired killings, at the very least,” she said in an interview. “Even citizens are being urged to kill. So what do you call it? People are being encouraged to kill, and they don’t seem to realize that, from a human rights perspective, if this remains unabated, then we’re looking at possible accountability for a crime against humanity.”

Yet she said that she has lost friends over her outspokenness, and that anonymous Internet users have targeted her in vicious online campaigns. Last week, Duterte himself attacked De Lima in a speech for “complaining” about his campaign, and accused her of having a a “driver and lover” who accepted money from drug lords.

“Any dissent now is being blocked, is being treated with a demolition job,” De Lima said. “Character assassination. And I’ve been a recipient of that.”

“We can discuss this for hours and hours, but the sad reality is Philippine society is, I don’t know what to call it,” she continued. “People are so desensitized to [the fact] that something’s wrong, but they don’t want to acknowledge it. Definitely, something is very wrong.”

Follow me on Twitter @JRKaiman

MORE WORLD NEWS

Welcome to France House, where Olympians dance, VIPs strut and the liquor flows freely

Turkey’s prime minister says only a transitional role for Syria’s Assad would be acceptable

Rarely subtle in criticisms, North Korea heaps scorn on diplomat defector

UPDATES:

Aug. 23, 7:21 a.m.: This article was updated with background information about the timing of the uptick in extrajudicial killings.

This article was originally published Aug. 22, 9:20 a.m.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.