‘Black spider memos’ lay bare Prince Charles’ musings, misgivings

A copy of the letter that

- Share via

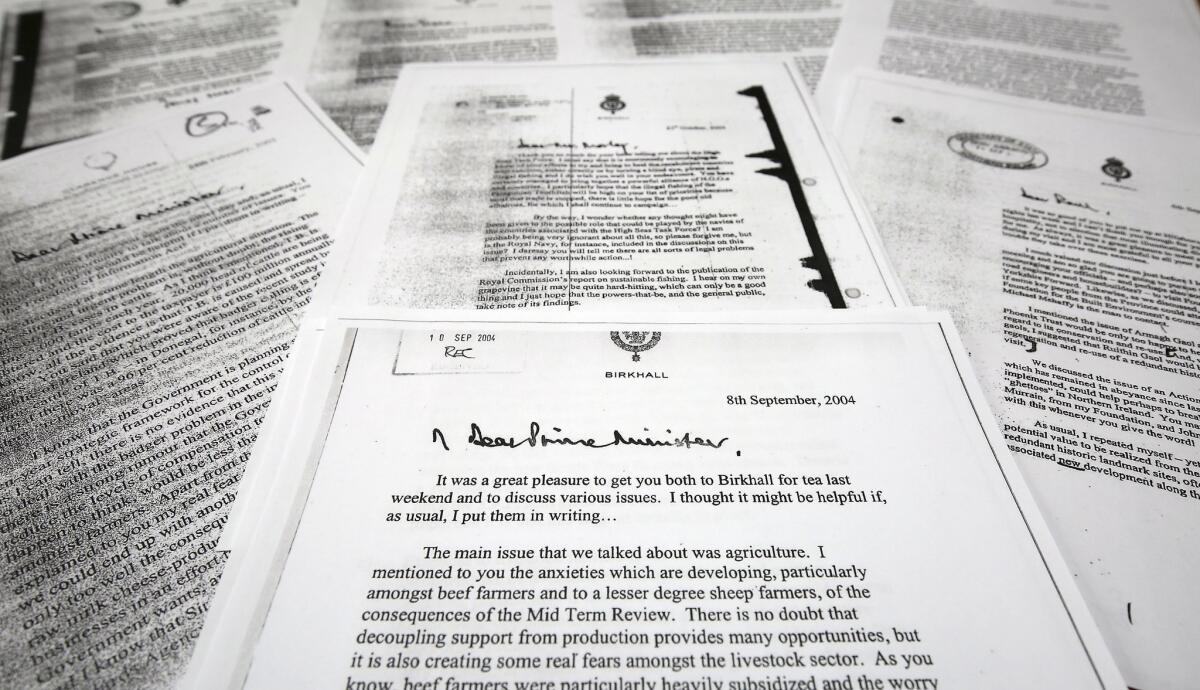

Reporting from London — Private letters Prince Charles wrote to government ministers have been released after a lengthy legal battle that went to the highest court in Britain.

The so-called “black spider memos” were made public Wednesday and lay bare the heir to the throne’s opinion on a diverse range of issues including resources for the armed forces, beef and sheep farming, reforms of the EU’s Common Agricultural Policy and even badger culling.

Supporters say the letters show a passionate, deeply knowledgeable prince who cares about the nation. Detractors argue he is abusing his position of authority, especially since as a future king he is supposed to be constitutionally impartial.

There are 27 letters, 10 from the Prince of Wales, 14 from ministers and three from private secretaries written between September 2004 and March 2005. They were released after a 10-year legal battle between the palace and the Guardian newspaper, which argued that there was a strong public interest in knowing what Prince Charles was writing to government ministers.

The request was initially vetoed by then-Atty. Gen. Dominic Grieve, who argued their disclosure might undermine Charles’ “position of political neutrality.” The fight went to the Court of Appeal, where that veto was declared unlawful, a decision upheld by the Supreme Court in March.

The letters were published on the Cabinet Office website and cover seven government departments while Tony Blair was prime minister.

They are called black spider memos because of Prince Charles’ messy scrawl, but in reality the letters are all typed.

Correspondence from the monarch and the heir to the throne are typically exempt from freedom of information requests, and restrictions have been tightened further since this legal fight, meaning it is unlikely royal correspondence of this nature will be released again.

As the memos were released, the palace issued a strongly worded statement expressing dismay that the letters were made public.

“The publication of private letters can only inhibit his [Prince Charles’] ability to express the concerns and suggestions which have been put to him in the course of his travels and meetings.” The statement asserts that the prince “cares deeply about this country, and tries to use his unique position to help others.”

Perhaps the most controversial letter is written to Blair after he and his wife, Cherie, had visited Charles on a weekend for tea. It details the prince’s concerns about the challenges the armed forces were facing in Iraq, especially the poor performance of Lynx helicopters.

Charles writes that the procurement of new aircraft to replace the Lynx is “subject to further delays and uncertainty due to significant pressure on the defense budget.” He adds: “I fear this is just one more example of where our armed forces are being asked to do an extremely challenging job (particularly in Iraq) without the necessary resources.”

It was written in September 2004 at a sensitive time in the deployment of British troops in Iraq.

The bulk of the letters cover issues in which the prince is known to have a deep interest. They include architecture, schools, and even Patagonian toothfish and albatrosses.

He also talks about how New Zealand Prime Minister Helen Clark lobbied him to address overseas funding to restore huts in the Antarctic used by explorers Robert Scott and Ernest Shackleton.

“I promised Helen Clark I would raise this issues with you - so I have!” he wrote in a 2005 letter to Tessa Jowell, who was then the secretary of state for culture.

His input appeared to have the desired effect: A few years later, the government gave about $400,000 toward their restoration.

Boyle is a special correspondent

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.