Ireland is voting on whether to lift its abortion ban — and the fight has been bitter

- Share via

Reporting from Dublin, Ireland — Abortion, long a taboo subject here, now dominates the public airwaves and conversations on the street as Ireland prepares to vote on whether to scrap a constitutional amendment that bans the procedure.

Women are sharing their stories about traveling for “job interviews” to England, where the procedure is legal, or being forced to carry a child to term when it has no chance of survival.

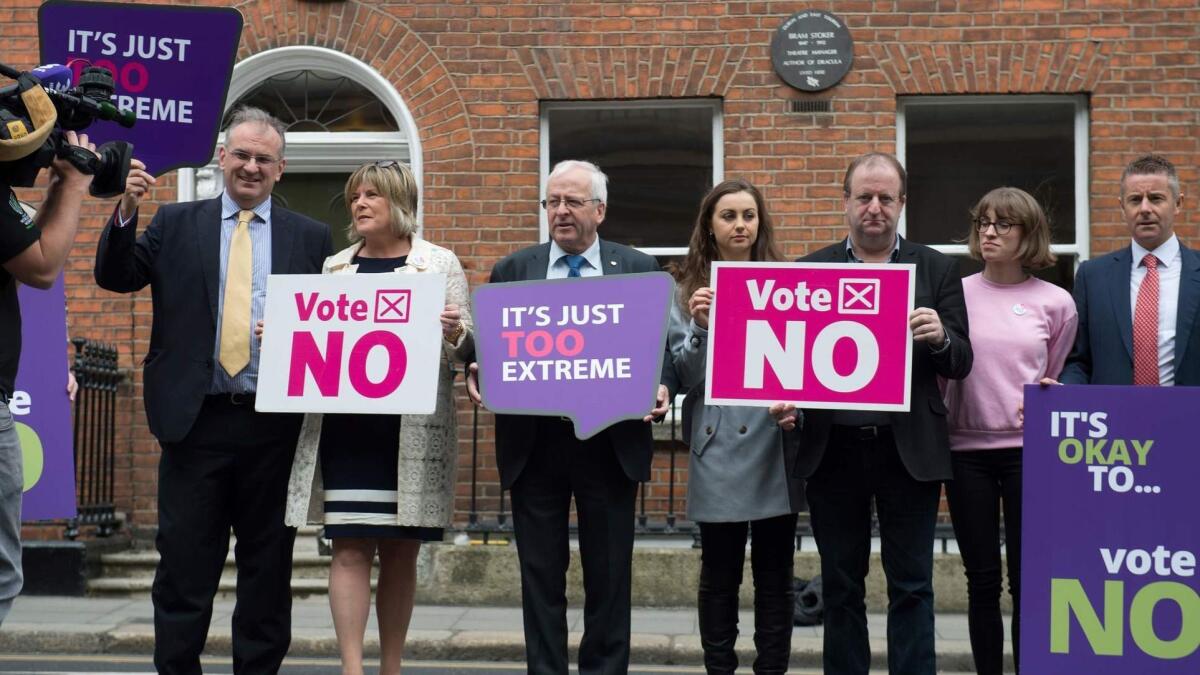

Posters for or against the proposed repeal compete for space on lampposts across the country.

“I am 9 weeks old,” says a “No” campaign advertisement featuring an ultrasound of a fetus. “I can yawn and kick. Don’t repeal me.”

“Sometimes a private matter needs public support,” says a “Yes” poster.

The referendum Friday is being portrayed as a once-in-a-generation vote. It will determine whether Ireland keeps the 8th Amendment, which grants equal rights to the life of the mother and the unborn and is the basis for some of the strictest antiabortion laws in the world.

The procedure is illegal even in cases of rape, incest and fatal birth defects.

The government has promised that if the amendment is repealed, it will bring its laws in line with those in several other European countries to allow abortions at up to 12 weeks of pregnancy or any time in cases of fatal fetal abnormalities.

“We cannot change the status quo in Ireland as long as the 8th Amendment remains in our constitution,” said Health Minister Simon Harris, who supports abortion rights.

Abortion has always been illegal in Ireland, but the amendment — passed in a 1983 referendum with two-thirds of the vote and the backing of the powerful Catholic Church — was seen as a guarantee on that ban. The Irish Constitution can be changed only by popular vote.

Attitudes have changed. A poll published by the Irish Times last week found 44% of potential voters supported the “Yes” campaign and 32% planned to vote “No,” with 17% undecided and 7% abstaining or declining to say.

“I grew up in an Ireland which wasn’t just a different country, it was another planet,” said Ailbhe Smyth, an abortion rights campaigner and veteran of the 1983 referendum battle.

One big difference between then and now is that the church, dogged by sexual abuse scandals, has far less influence.

Another major influence on the shift is the case of Savita Halappanavar, an Indian national who died of a bloodstream infection known as septicemia in 2012 after an Irish hospital denied her a medical abortion as she was experiencing a miscarriage.

The case, which energized abortion rights activists and led to major demonstrations, resulted in passage of a law in 2013 that created a rare exception to the ban by allowing abortions in cases when three doctors agree that a mother’s life is in danger.

Halappanavar’s face now appears on posters for the “Yes” campaign.

Proponents of repealing the amendment argue that abortion is already common — each day nine women travel to England for the procedure and three more use illegal abortion pills without medical supervision, according to Irish government — and that lifting the ban would make it safer.

Harris called the 8th Amendment a “failed experiment.”

But antiabortion activists argue the constitution is correct to uphold the sanctity of unborn life and say the government has twisted the debate by highlighting cases such as Halappanavar’s.

“What’s at stake is whether unborn babies are being protected or whether they’ll be killed,” said Niamh Ui Bhriain, who heads the Save the 8th campaign.

“Right now in Ireland we have a culture and a constitution that protects the right to life of both mother and baby, and that serves us very well,” she said.

“Abortion on demand fills me with horror,” said Rosemary Lennon-Maher, a volunteer handing out glossy red “No” pamphlets this week in Dublin.

“I hold life as sacred and I think it’s a basic human right for every human being that they get the gift of life,” she said.

Emotions on the issue run so high that many Irish citizens living abroad have returned to vote in the referendum. On one Facebook group, members have donated at least 200 flights to supporters of the “Yes” campaign.

Noncitizens have also joined the debate.

Members of Students for Life of Michigan, an antiabortion group, has been traveling around Ireland for two weeks spreading its message.

“I’ve been surprised at how many people are happy we’re here,” said Nicole Hocott, a student at the University of Michigan and president of the group.

Facebook announced this month that it would stop publishing all foreign-funded ads related to the referendum, heeding Irish laws that prohibit donations to political groups by noncitizens. Google followed suit with a similar ban.

Transparent Referendum Initiative, an independent group that has monitored online ads during the campaign, said those efforts have failed to stop influence by foreigners and unnamed lobbyists.

“What we have seen is that essentially our democracy is up for sale to the highest bidder and that bidder can remain anonymous and get around attempts at self-regulation,” it concluded in a report.

Whatever the outcome of Friday’s referendum, the dueling campaigns have largely removed the stigma of discussing experiences with abortion.

“I don’t want an abortion, but I need one, and I’m about to get one,” Tara Flynn, an Irish actor and comedian told a Dublin audience at a recent performance of her one-woman show, which weaves personal experience, reflection and song into a journey through sex, history and religion.

She went on to describe herself in the waiting room of a Dutch abortion clinic in 2006, frightened and alone, but undeterred.

Casey is a special correspondent.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.