Great Read: In China, clans’ fortress homes abandoned for modern amenities

- Share via

Reporting From Tianzhong, China — From the sky, some are shaped like doughnuts. Others take the form of squares and ovals. The structures are so strange and fantastic that American intelligence officers analyzing satellite images during the Cold War initially suspected they were missile silos or part of a nuclear complex.

Seen from the ground here in southeastern China, though, it’s clear these fortresses — with thick walls and a single, heavily fortified entrance — were designed not for offense, but for defense. And they’re hardly modern technology.

------------

FOR THE RECORD

Jan. 9, 2015: This article quoted Dana Wu, whose family has launched a program to conserve one of the buildings, as saying the effort was a “profit-losing corporation.” Wu said it was a “profit-losing operation.”

------------

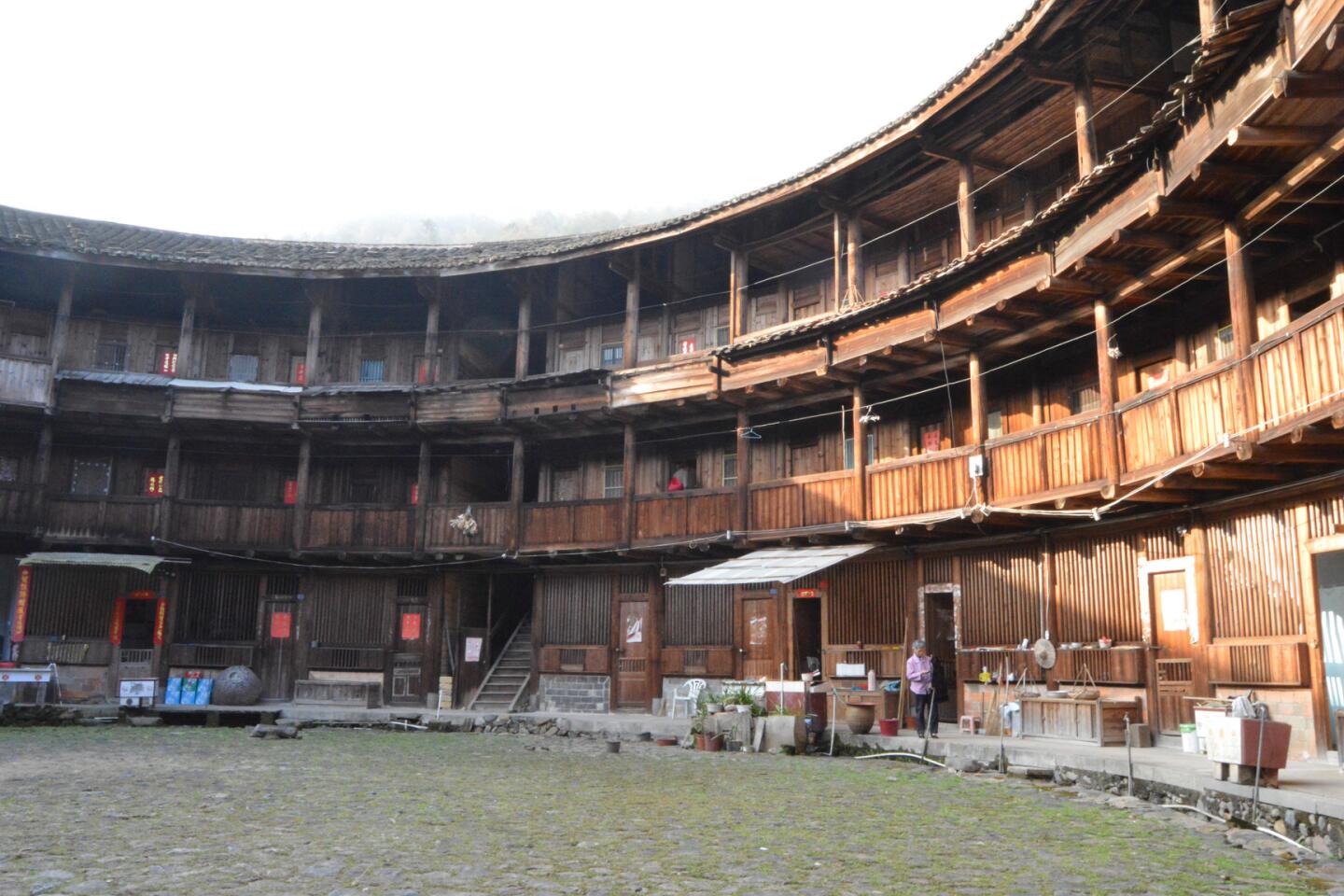

Since the 12th century, the Hakka and Minnan people in Fujian province have concealed and protected themselves inside tulou, rammed-earth apartment complexes lined with wood-framed rooms facing a communal courtyard. Each clan would build its own tulou over a period of years; some are small, housing only a few dozen people, others can hold more than 500.

Traditionally, everyone living in the tulou would share a family name, with the building providing both a haven from bandits and a sense of community.

But that’s unraveling. Amid rising incomes and expectations, residents — especially young couples with children — are abandoning the tulou way of life.

They’re building boxy concrete homes with more privacy and modern amenities such as indoor plumbing and air conditioning, emptying some tulou entirely and turning others into de facto senior citizens’ homes.

“China’s traditional tulou will eventually become museums, maybe even within the next generation,” said Fang Yong, a professor at Peking University’s School of Archaeology and Museology who has studied the structures extensively. “They’re inconvenient and cannot satisfy the demands of contemporary people.”

In 2008, UNESCO listed 46 of the most spectacular tulou on the World Heritage List. The United Nations designation has brought a wave of tourists to this largely agricultural region, where residents now hawk tea, tobacco, herbs and handicrafts to urban visitors, or charging them about $1 to poke their heads into their homes.

But academics, preservation groups and residents say the clock is ticking on tulou as living, breathing communities.

Figuring out a way to preserve both the physical structures and the intangible cultural and social heritage imbued in buildings inhabited by sprawling clans over centuries is a major challenge.

Five years ago, the Palo Alto-based Global Heritage Fund initiated a tulou preservation project, but its efforts stalled amid a dearth of strong local partners. The organization hopes to revive the effort next year.

“The ideal situation is to have people still live in them, but how do you convince people to live in a five-story mud house?” said Vincent Michael, the group’s executive director. “It doesn’t have as much cachet these days.”

::

A spray of lime green and tangerine fireworks whistled over Tianzhong on a brisk Saturday night last month, fired into the sky by a local family celebrating its move into modernity.

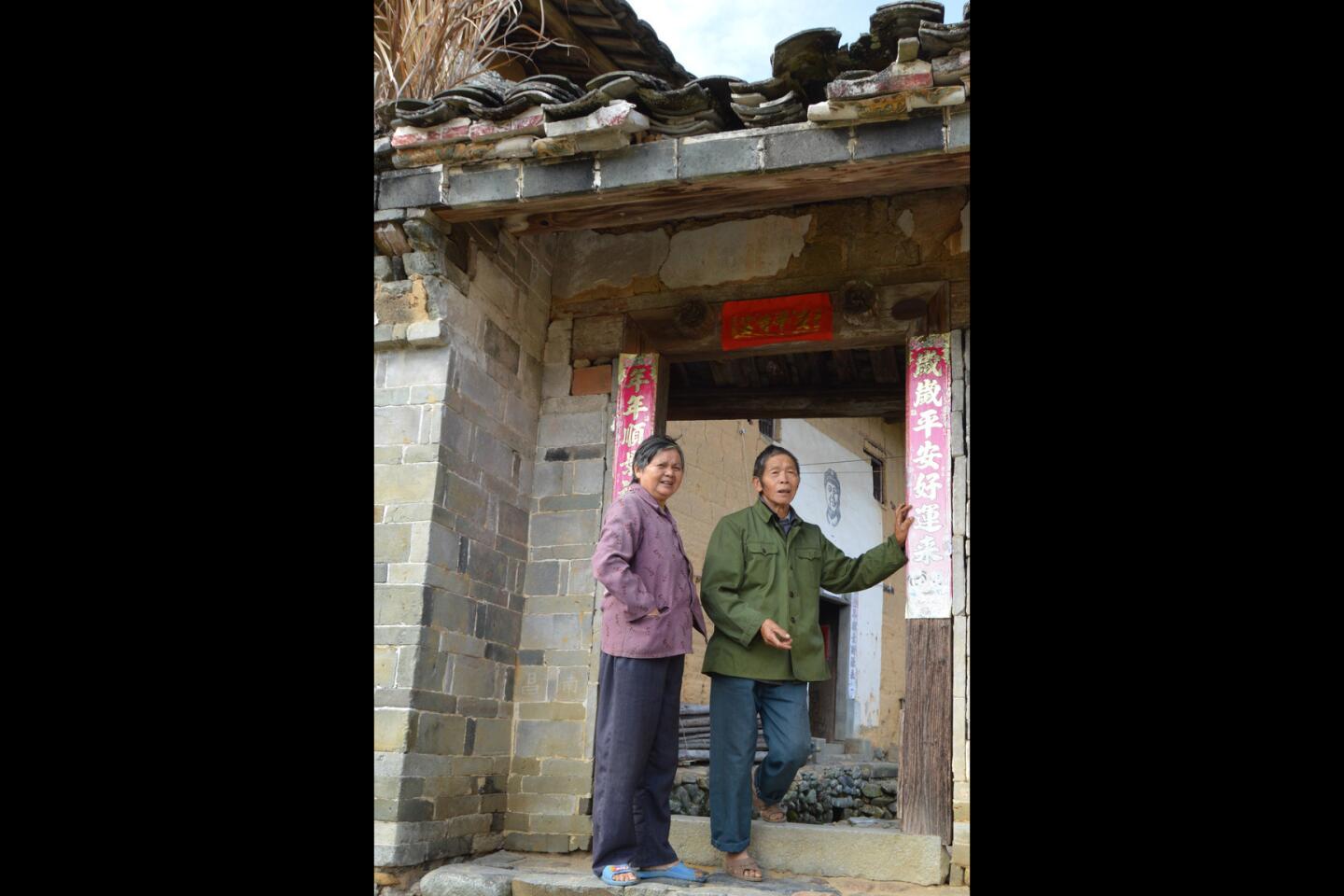

A few hundred feet uphill from the pyrotechnic show that celebrated construction of the village’s newest house, Huang Maoyou, 67, and Xiao Dashi, 73, cling to the simple life in their 400-year-old tulou. They’re the only residents left in the two-story building, which has more than a dozen rooms.

Many tulou proudly bear appellations over their doorways such as Dragon’s Den or Five Phoenixes, but the entryway of the aging couple’s home is adorned with a smiling portrait of Mao Tse-tung. The sun has bleached the chairman’s once-red sun halo to a faint shade of peach.

Just inside the threshold of the fortress, a rough-hewn timber and stone gristmill is covered with dust. In the cobblestoned courtyard, Huang drew water from a well lined with green fern fronds and put a kettle on her outdoor stove. A group of foreigners on a bicycle tour had dropped by, and Xiao was eager to pour them some local tea from his pink Mickey Mouse thermos.

“My sons and daughter have all moved to the city, but I can’t stand to live there,” said Xiao, who refuses money from his visitors. “I can’t read, and I prefer to stay here and work in the fields.”

Xiao thinks that he and his wife will be the last inhabitants of his tulou, but he’s unperturbed. “It’s just the way life is,” he said, shrugging.

Xiao was born in a nearby tulou that’s now abandoned. Fujian’s lush and aggressive tropical foliage has wasted no time moving in and is quickly swallowing the structure.

Around the bend, a tulou called Qingxing made a bold move aimed at avoiding a similar fate. In 2008, the 30 largely inter-related families who jointly owned the structure agreed to lease it long-term to a Seattle-based Chinese American family. During Mao’s 1966-76 Cultural Revolution, the U.S. family’s patriarch, then a teenager, had been sent to work in Tianzhong and developed close ties with residents of the tulou.

“Ever year, my family would go back to visit and see there were fewer and fewer people to maintain it. My mother, who studied architecture and is sort of a sustainable buildings advisor, had the idea to try to preserve it,” said Dana Wu, 26, an architecture student at Harvard. “My mom thought we could keep the building alive by reusing it.”

The dozen or so mostly elderly residents still living in the building — erected between 1950 and 1961 — were allowed to stay on. Wu’s parents repaired some of the wood in the tulou and added modern bathrooms on each floor.

Creating a nonprofit called Friends of Tulou, the family now invites small groups of scholars and students to stay from time to time in about 50 guest rooms. The tulou has also hosted company retreats and theatrical performances; visitors make donations to contribute to the upkeep.

Travelers are free to explore the building’s ancestral hall (which doubles as a bike parking zone), ramble through its wooden corridors and chat with its resident grandmothers as they work in their courtyard kitchens.

But even with its updates, Qingxing can appeal to only a certain set of travelers: the ones who find charm in the screech of Chinese opera blaring from a resident’s TV and tolerate the odor of chamber pots, still favored by the tulou regulars over contemporary commodes.

“We’re a nonprofit but so far, it’s probably more accurate to say we’re a profit-losing corporation,” Wu said. “We have people there every few months, but we’re deliberately moving slowly because we don’t want to overwhelm the community.”

Even the more business-minded say repurposing tulou is financially challenging.

Jian Xuezhen converted the Wind Cloud tulou in Kanxia village more than a year ago into a hotel, spending several hundred thousand dollars to add bathrooms, hot water and even Wi-Fi. He charges $15 to $20 a night for a room, but hasn’t seen many guests outside peak holiday times such as National Day in October and Chinese New Year.

“I’ve lost some money already,” Jian said.

Some nights, the only person in the building is an 89-year-old woman whom Jian allowed to stay on when he acquired the building.

::

One man who’s making a go of things is Stephen Lin, a sixth-generation inhabitant of the Fuyu tulou in Hongkeng village, 14 miles from Tianzhong, near a cluster of UNESCO-registered buildings. Lin’s 134-year-old building has 160 rooms; one wing with 19 rooms has been converted into a hotel, and 50 other clan members occupy the rest of the structure.

Lin’s family got into the innkeeper business about 12 years ago, and his clientele is now about 40% foreigners and 60% Chinese. The structure’s architecture, he noted, keeps visitors and permanent residents relatively separate, but guests like the idea of staying not in a “hotel-hotel, but a real living tulou.”

Bruce Foreman, who runs a cycling tour group called Bikeaways and has visited the region more than a dozen times this year, agrees.

“I really like to see authentic tulou with people still living in them, that human connection to the past,” he said. “If you want to see that, you’ve got to get there within the next 10 years and you’ve got to get off the beaten track. Don’t follow the bus route.”

But in some ways, Foreman said, outsiders shouldn’t fixate on the idea that the abandonment of some tulou and the commercialization of others — including a cameo in a new Chinese period film by director Jiang Wen, “Gone With the Bullets” — amount to a cultural travesty. The UNESCO designation, at least, is protecting some amazing structures that otherwise might vanish.

Fujian provincial tourism authorities hailed the inclusion of the Yongding area tulou in Jiang’s film, saying they hoped it would attract more visitors to the region. They staged a ceremony with the director for a “cooperation agreement” and presented him with a little model of a tulou.

“The clans themselves endure and they are finding new ways to keep the clan alive outside of the tulou,” Foreman said. “They see the clan as important; they don’t see the tulou as important. They don’t have that sentimentality, so should we?”

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.