Clues from the mists of time

- Share via

Kuelap, Peru

The broken skeletons were scattered like random pottery shards, rediscovered where they had fallen centuries ago.

Were these ancient people cut down in some long-forgotten battle? Did European-introduced diseases cause their demise? Were they casualties of some apocalyptic reckoning at this great walled citadel?

The “cloud warriors” of ancient Peru are slowly offering up their secrets -- and more questions. Recent digs at this majestic site, once a stronghold of the Chachapoya civilization, have turned up scores of skeletons and thousands of artifacts, shedding new light on these myth-shrouded early Americans and one of the most remarkable, if least understood, of Peru’s pre-Columbian cultures.

Among the arresting findings: the practice of incorporating the dead into defensive walls; the use of stone missiles to repel invaders; the discovery of gargoyle-like stone carvings; and the civilization’s sudden collapse, possibly in a final, purifying conflagration.

Though almost everyone knows about the Inca and Machu Picchu, relatively few have heard of the Chachapoya or visited their domain, a vast swath of Amazon headlands and breathtaking cloud forests on the slopes of the Andes. This walled settlement, among the largest monuments of the ancient Americas, rivals the Incas’ Machu Picchu in scale and grandeur.

Getting here requires a lengthy, bone-crunching journey on roads less traveled, near-vertical jeep tracks featuring better-not-to-look drops of 1,000 yards or more. Kuelap is in the middle of nowhere, and there is no midday buffet, five-star hotel or luxury locomotive -- amenities found at Machu Picchu, 600 miles to the southeast.

“You have to have an adventurous spirit to come to Kuelap,” said Alice Cook, 25, a schoolteacher from Alaska who was hiking down after a day’s visit. “It’s not like just getting on the train and you’re here.”

The Chachapoya civilization is believed to have thrived from around 800 to about 1540, the last 70 years or so under the domination of their empire-minded neighbors, the Inca, and then the Spanish. The Chachapoya, historians say, were a loose confederation with settlements spread across a 25,000-square-mile swath of north-central Peru -- an area about the size of West Virginia -- and may have numbered 300,000 people or more at their height.

Serious scholars and swashbuckling, would-be Indiana Joneses alike have set out to find “lost cities” long reclaimed by forest and jungle, succumbing to the allure of a civilization that dominated for centuries, then mysteriously disappeared.

But dubious assertions about Chachapoya origins have sometimes trumped sober research. Colonial-era reports that the Chachapoya were somewhat lighter-skinned than other groups have fanned improbable theories about their origins.

“It’s a place plagued with ideas that it was colonized by everyone from blue-eyed Phoenicians to Irishmen paddling their cow-skin boats across the Atlantic,” said Keith Muscutt, a Santa Cruz-based explorer, academic and author who has written a book about the Chachapoya. “For a generation or two there have been absurdly sensational claims that have acted to the detriment of archaeology.”

Known from colonial chronicles as tall and fierce warriors who long resisted the Inca, the Chachapoya were also far-ranging merchants and powerful shamans.

Exotic plumage and intricate jewelry carved from seashells found here and elsewhere attest to their position as strategically placed traders who probably roamed from the Amazon jungle to the Pacific coast. Items bartered included prized coca leaves, feathers of tropical birds and hallucinogenic plants. Their archaeological legacy, however, points to something more profound than a mercantile society.

“Although the Chachapoya played a part in the greater Andean cultural sphere, their art and architecture convey a bold, independent spirit that distinguishes them from their neighbors,” wrote Adriana von Hagen, a Peruvian journalist and scholar.

The Chachapoya typically built on high ground, which offered defensive position and drainage in a region where enemies were abundant and rains torrential. Farmers terraced hillsides below for potatoes, maize, and other crops, sustaining large populations where few live today.

Though many stone-built Chachapoya sites have been found, and others probably remain concealed by lush vegetation, the citadel here, with walls approaching 60 feet in height, radiates an unsurpassed grandeur. The wall, which varies in height as it snakes along a verdant ridge, is composed of dozens of rows of limestone blocks of varying sizes and shapes, some weighing several tons, all precisely cut and wedged into place in an impressive feat of meticulous construction.

From a distance, Kuelap, at an altitude of 9,500 feet, appears like the prow of a behemoth ark that outlasted some primordial flood and was left perched on a hilltop, dominating the cloud forests, the misty realm between towering Andean peaks and the low-lying Amazon flood plain.

The existence of Kuelap has been publicly known for more than a century. But in contrast to Machu Picchu, which became an international sensation after a Yale explorer, Hiram Bingham, declared its “discovery” in the early 20th century, Kuelap’s isolation long thwarted serious research. Waves of determined looters and the curious carted off bones and other remnants.

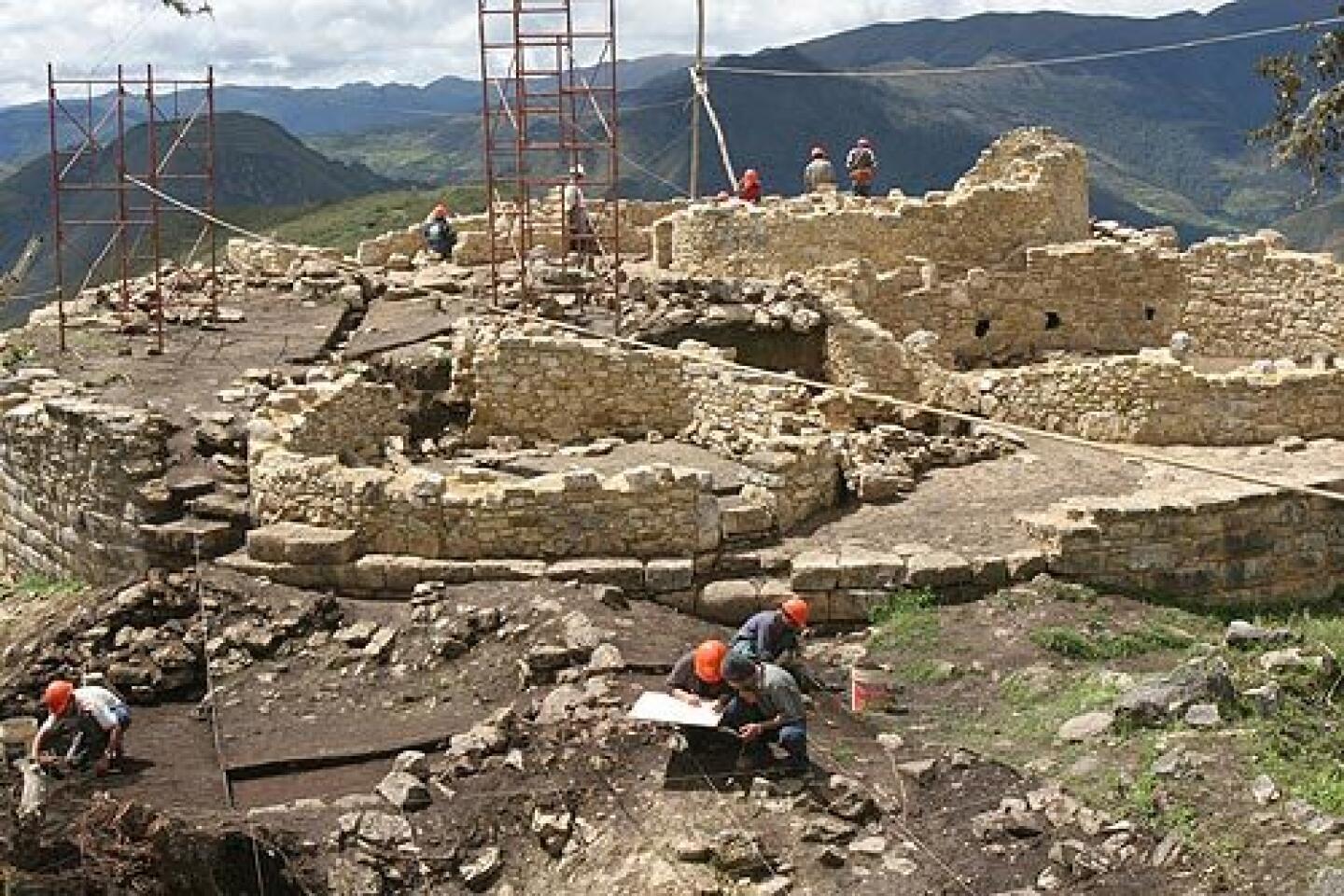

Now, Kuelap is slowly yielding its mysteries to the most rigorous scientific excavations to date, financed by the Peruvian government and the state of Amazonas.

Arriving in Kuelap on a recent day amid the frenzy of archaeological work provided a hint of how dynamic it must have been when several thousand people, possibly a priestly class, resided within the walled compound. Inside the 15-acre enclosure, which has the feel of a medieval fortress, researchers have found more than 500 structures, mostly round stone dwellings that once featured conical, thatched roofs.

Entry is via claustrophobic corridors, with space at some points for only a single person. Whether this was a defensive measure or a design conceit remains unclear. Worn into the smooth stone of one passage are the hoof prints of countless llamas, beasts of burden and a source of food.

Interior walls feature geometric friezes, sculptured serpents (the snake was a sacred symbol) and glaring stone faces -- eerie, unnerving visages from a lost era. The perpetual stares convey an enduring sense of reproach, as though disapproving of contemporary efforts to unearth the Chachapoya secrets.

Today, dozens of archaeologists and their assistants, armed with shovels, picks, brushes, pens and paper, endeavor to peel back the layers of dirt and debris and unlock the enigma. At roped-off digs, pieces of half-interred pottery and skeletal remains are clearly visible.

“We found these,” said a grizzled, orange-helmeted Modesto Velazquez, a laborer who is part of the archaeological team, bearing several ancient deer antlers that served a decorative and possibly utilitarian purpose, an ancient version of coat hooks.

Seated on the edge of a platform built atop the exterior walls, Tomasa La Torre, a conservationist, mapped a ceremonial site that has yielded bones and curious stone corrals where the Chachapoya kept cuy (guinea pigs), still a dietary staple in Peru. In the chasm below, workers strive to bolster the integrity of stone walls worn by time and storms.

Looming at the top is the so-called Plaza Mayor, a towering structure shaped like an inkwell that may have been the first construction here. Evidence such as bones, food offerings and a miniature condor carved from seashell point to a place where rituals were performed and offerings made to deities.

“We think this was the ceremonial heart of Kuelap,” said Julio Rodriguez, a supervising archaeologist.

There’s no denying the fortification motif. On a guard tower at the lush north end, where moss- and orchid-dripping trees provide a ghostly aura, archaeologists have unearthed thousands of stone missiles, apparently projectiles to be hurled down at intruders.

Recent evidence points to the central ritual significance of Kuelap, which was probably constructed over generations, testament to an elite’s ability to draw labor, likely to have been volunteer, for projects of communal interest. Even the massive walls served a funerary purpose in a culture that revered ancestors. Many bones and entire skeletons were embedded in the exterior ramparts. The Chachapoya dead enjoyed an active afterlife.

“You’re surrounded by your ancestors and they protect you,” said J. Marla Toyne, a Canadian physical anthropologist. “The idea may have been that people contributed a part of their lineage to the construction, to give the building life.”

The Chachapoya were indeed keen to keep their dead nearby: wedged into walls, buried beneath the floors of homes, placed in highly decorative mountain sarcophagi.

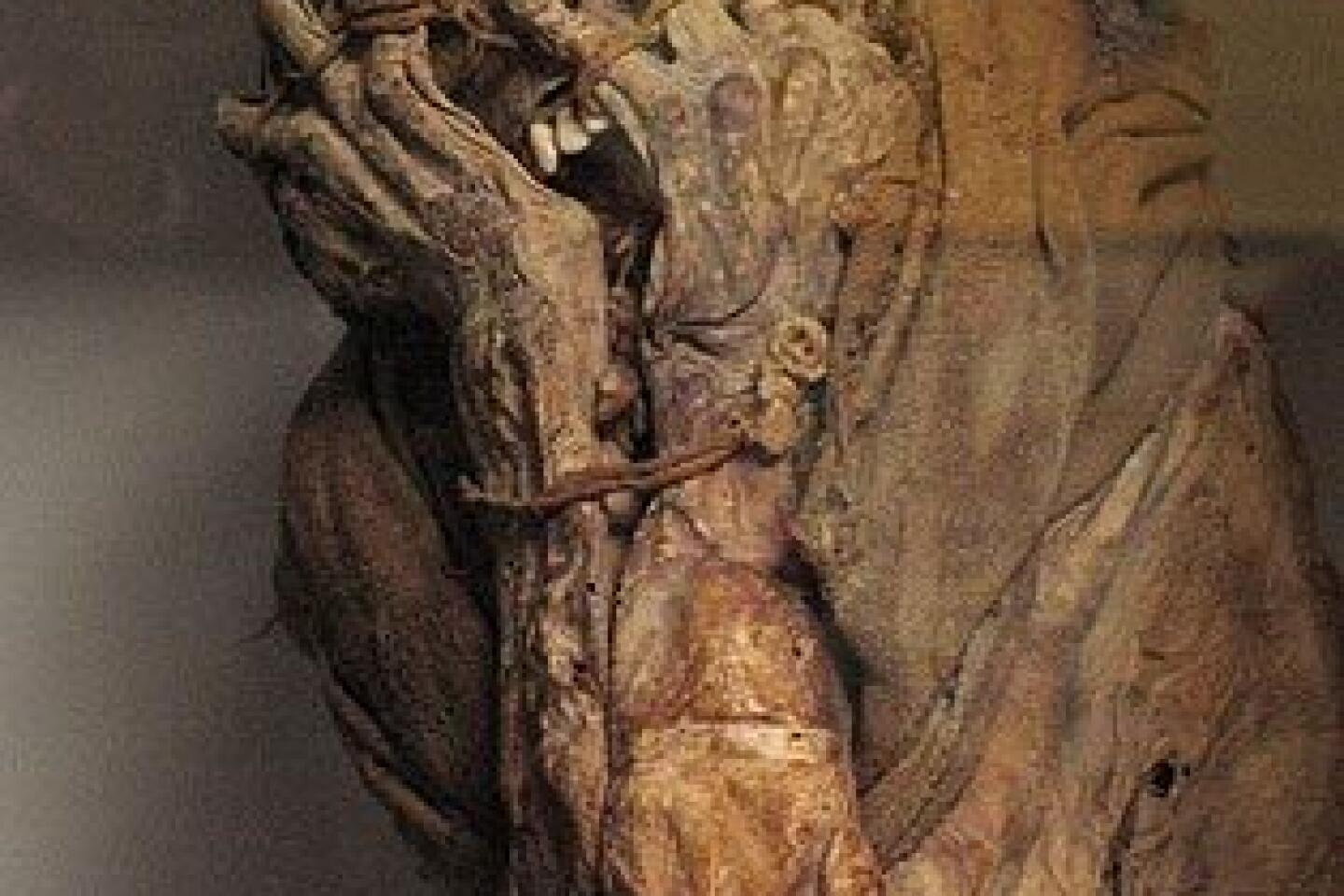

Most impressively, they practiced mummification: A breakthrough in Chachapoya scholarship was the recovery a decade ago of more than 200 well-preserved mummy bundles from a steep cliff above a sacred lake known as the Lagoon of the Condors.

One mummy, now unwrapped and on exhibit at a museum in nearby Leymebamba, was probably an Inca administrator, his pierced lobe that once held an ear ornament still evident, his still-bright teeth indicative of ample nutrition.

The Chachapoya apparently eschewed ear jewelry in favor of bone ornaments in their pierced noses. A mummified young girl displayed skull wounds possibly consistent with human sacrifice. A mummified wildcat was also found, an indication the feline may have been revered.

Along with fine textiles used to wrap the dead, the cliff burial site yielded some of the best examples of khipu, dyed and knotted strings that Inca administrators used to keep census data, records of tributes paid and other details.

The archaeological evidence is that the Chachapoya adapted to their Inca overlords, however much they may have resented them.

“The two groups seem to have eventually reached a kind of mutual accommodation,” said Sonia Guillen, a forensic anthropologist who is Peru’s foremost authority on mummies.

The apparently sudden decline of the Chachapoya in the first half of the 16th century, and their obliteration from the map, is a theme that has confounded experts. Today, the only trace of their language is in place names such as Kuelap, whereas Quechua, a version of the tongue spoken by the Inca, is widely used in Peru and Bolivia.

“The Chachapoya suffered a demographic catastrophe in a short period of time,” said chief archaeologist Alfredo Narvaez, noting that the population had probably dropped from several hundred thousand to perhaps 10,000 by the mid-16th century, after the arrival of the Spanish in Peru.

Scholars say the Chachapoya quickly allied themselves with the Spanish against their Inca overlords.

But whatever benefits collaboration brought were probably short-lived. European diseases decimated Andean and other New World populations lacking immunity.

Evidence of a possible final calamity at Kuelap has been found in a platform near the Plaza Mayor, where excavators discovered scores of randomly scattered skeletons, of all ages and both sexes, mixed amid daily utensils. This was a striking departure in a culture in which departed loved ones were treated with great care and ceremony.

“Why these remains were concentrated here and not properly interred is a big question,” said Edwin Blas, a supervising archaeologist standing over the platform.

Researchers are treating the site like an ancient crime scene. Some have speculated on a climactic battle. Or the remains could be of people who succumbed to disease.

The area also shows evidence of a great fire, Narvaez says. He speculates that it could have been deliberate destruction of the grand structure as it was abandoned, a kind of ritual purification found at other pre-Columbian monuments. It would have been a hallucinatory moment, and a somber one, the blazing conclusion of an epoch.

The bones and other artifacts newly unearthed are being collected, cleaned and cataloged. Local women have been hired to help. Seated at outdoor tables below plastic tarps, they use toothbrushes to scrape off centuries of dirt and grime from femurs, ribs, skulls and other remnants of a civilization that once reigned from the steamy valleys below to these dizzying heights.

“They had strong bones and good teeth -- much better than ours,” said Maria Huaman, 56, as she scrubbed a skull that featured a large hole, possible evidence of a crude form of ancient brain surgery. “I believe that our ancestors led very healthy lives.”

patrick.mcdonnell

@latimes.com

Photographer Liliana Nieto del Rio in Kuelap and Andrés D’Alessandro of The Times’ Buenos Aires Bureau contributed to this report.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.