Inside India’s epic effort to bring electricity to millions of people for the first time

- Share via

Anita Chauhan crouched over a flame in the semi-darkness, flipping rotis by the pale yellow light of a kerosene lamp. Smoke filled the shed and wafted into the cool, moonlit forest.

Chauhan hated the lamp. The fuel was expensive, and adjusting the glass singed her hands. Combined with the burning wood, the risk of fire was great. But her husband, Ganpath Singh Chauhan, didn’t like her cooking in the dark.

“What if insects crawl into our food?” he worried.

POWERING INDIA: The appliance that could set back India's climate goals »

After dinner she sat at the foot of the bed holding their 2-year-old daughter. Ganpath Singh studied a day-old newspaper by the cold white beam of a flashlight, charged from the family’s weak solar battery.

They fell asleep early, as farmers do in these rugged hills in northern India. But as Chauhan closed her eyes, she felt a glimmer of excitement.

The next day, they would get electricity.

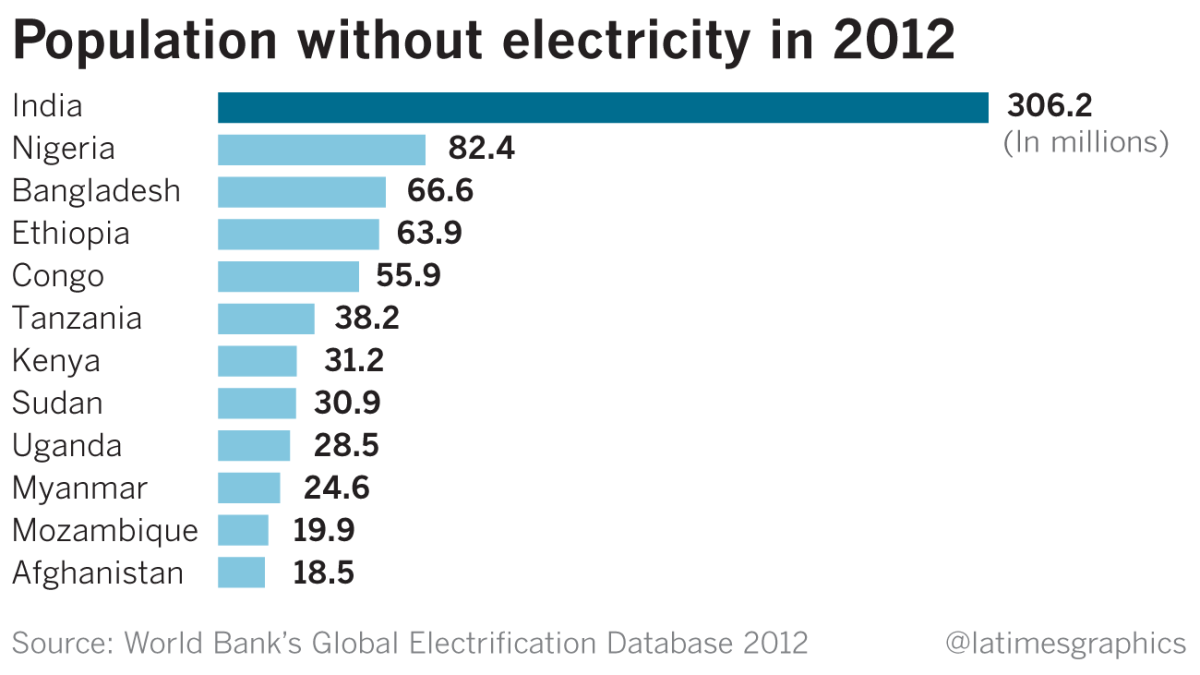

Seventy years after independence, India is racing to connect thousands of villages to power grids for the first time, a mammoth undertaking that aims to reach more than a quarter of a billion people who lack electricity and accelerate the country’s rise into the ranks of the world’s great economies.

The rural electrification drive also seeks to solve one of India’s most vexing contradictions: A country known for producing armadas of engineers and high-tech hubs that serve Fortune 500 companies still includes a vast hinterland where children study by flickering lamps, women hike long distances to collect firewood and men send their cellphones miles away to be charged.

In Barnali, an apple-growing community perched on a wooded slope in the Himalayan foothills, farmers had petitioned government departments for two decades asking to be connected to the power grid.

Solar batteries were unreliable, and difficult to charge between summer monsoons and winter storms. Families effectively lived only half their days, their movements all but frozen once the sun dipped below the rugged peaks to the west.

One day last year, a group of technicians drove into the village along the winding mountain road, armed with fancier smartphones than the Chauhans were accustomed to seeing. They snapped photos of the steep terrain and took down everyone’s names.

A few months later, a team of men in hard hats guided a 300-pound metal pole down the hillside and planted it on a patch of dirt below the apple orchard where two Chauhan brothers live with their families. The workers strung a cable through the beams of their long concrete house and hammered an electric meter into the wall.

The morning that the power was to go on, a half-dozen members of the Chauhan clan stood on their veranda under a cloudless sky. Talk turned to a heady future filled with appliances, and soon a debate broke out.

What kind of stove should they buy? How many lamps? Should they get an iron or an electric flour mill? Would the family’s older children, studying in a distant town, come home more often if they had a TV?

Anita Chauhan was nearly 40. Such a transformation at this stage of her life was hard to imagine.

“I really think that light will change everything,” she said.

Americans think nothing of plugging a cord into a wall at home and being rewarded with a beam of light or the whir of a machine. It was not always that way: It took the Rural Electrification Act in the 1930s to bring power to most farmhouses.

In India at the dawn of the 21st century, electricity was far from a given in many cities.

Schoolchildren endured year-end exams without fans or air conditioners, soaking their test sheets in pools of sweat. Women lit gas stoves with matches and families slept with windows open in the summer to let in the slightest breeze.

In rural areas, India’s central planners had focused on providing electricity for agricultural production, but powering households was not a priority. As India’s economy boomed, its predominantly state-run electricity companies struggled to meet the demands of cities while villages fell further behind.

The World Bank reported in 2015 that 311 million Indians — one-quarter of the population — lacked reliable power, nearly all in the countryside. India, which has four times the population of the United States, can produce one-quarter as much electricity: about 330,000 megawatts, more than half of which comes from coal.

As studies have underlined the benefits of universal electricity access — better educational outcomes for children, greater school attendance for girls, lower risk of respiratory illnesses brought on by kerosene use, and increased security — successive Indian governments have promised to bring power to all.

In 2005, India introduced a rural electrification plan that included free connections for its poorest citizens and better transmission lines in rural areas. A decade later, with more than 18,000 villages still lacking electricity, newly elected Prime Minister Narendra Modi rebranded the program and pledged $5 billion as part of a push to modernize India’s economy.

But since 2015, only 1,200 villages have seen all households joined to the grid. Officials say the slow pace reflects the difficulty of the task.

“It’s one of the biggest public sector undertakings India has ever done,” said Dinesh Arora, a former head of the state-run Rural Electrification Corp. who now leads NITI Aayog, a government think tank.

“The remaining villages are really the toughest to access. They are on mountaintops, deep in the forests, in insecure areas. In some cases we are the first central government department to reach these places.”

::

From Dehradun, the capital of Uttarakhand state, Barnali is 50 miles away as the crow flies — a distance that takes nearly eight hours to cover by road. It begins in a dusty valley and twists skyward through green carpets of farmland, babbling streams, thick pine groves and hamlets marked by desolate tea stalls.

The center of Barnali was electrified in the 1980s, but power was not extended to about two dozen houses in the hills above the village, where the Chauhans have farmed a one-acre plot for generations. Ganpath Singh, his brothers and their wives spent carefully and did the toughest work themselves. Their apple crop now fetches $30,000 in a good year, a decent income by Indian standards.

But the lack of electricity belied that success.

When her daughter Mannat awoke hungry in the middle of the night, Anita Chauhan, a slender woman with a beaked nose, fumbled in the dark for a flashlight or lantern. In the mornings, to fortify the family for a day’s work in the fields, she mixed lassis — Indian smoothies of yogurt, sugar and spices — by hand until her forearms ached.

At night she milked their cows and — with no water heater — took a cold shower before spending an hour cooking dinner in the smoky wooden kitchen shed.

Her elder sister-in-law, Manmala, a primary school teacher in a nearby village, sometimes showed up to work only to find a last-minute holiday had been declared. Her students watched television at home and stumped her with questions about the news.

“If there’s a bus crash and they ask, ‘How did it happen, how many people died?’ I shouldn’t have to ask someone else,” said Manmala, a stern, broad-shouldered 40-year-old. “As a teacher I should have better interactions with the children.”

Raised 10 miles away in a village that had electricity, Manmala struggled to adjust after she married Ganpath Singh’s older brother, Bijender Singh, and moved to Barnali. Her two sons attended college in Dehradun and came home only once a year.

“There is nothing here for them, no way to study for exams or relax in front of the TV,” she said. “They call every day, asking, ‘Has light arrived?’”

Several years ago, basic cellular coverage reached the village, but the phones proved more trouble than they were worth. The signal was spotty, and to recharge a battery usually required trudging 20 minutes down into Barnali to plug into a socket.

“There is no point in raising a family here,” said Anupa Rawat, a 45-year-old mother of two who lives below the Chauhans. Her sons worked outside the state for much of the year and, when they returned in summers to help with the apple harvest, spent nights in the village with friends, falling asleep to cricket matches on TV.

“I’ll be relieved when light comes,” Rawat said. “Someone looking at this place from far away wouldn’t even know there was life here. It’s like we don’t exist — until now.”

A technician climbed up a silver-and-yellow electrical pole above the Chauhans’ farm, his polo shirt flapping in the wind. He fixed one last piece of high-tension cable, allowing current from a power station 20 miles away to reach the houses along the hillside.

Gulshan Kumar, 24, watched from below and tapped out notes on a cellphone app. As one of 400 rural engineers hired under the Modi government’s electrification plan, Kumar had traveled to more than 70 villages to track the establishment of power connections.

Walking miles in his beat-up Pumas, he showed off cellphone pictures of his work like trophies: leaping across a stream with his jeans pulled up to his knees, scaling a sheer cliff with a dog trailing behind him. It was not the standard engineer’s job he expected when he joined the Rural Electrification Corp. in 2014, but it was part of the agency’s fresh approach, deploying young staffers like humanitarian aid workers and developing an app to track progress village by village.

“My job is like an NGO, to provide help to the people … to give them electricity and their basic needs,” Kumar said.

A few hours later, as the sun dipped below the hills, Ganpath Singh trudged in from the apple orchard. Anita was in the shed, cooking potatoes.

“Is the power on?” he asked.

“I don’t know,” she shrugged. “I didn’t switch on the light because I thought it would attract mosquitoes.”

He wiped his hands on his trousers and scooped up his daughter, pulling a wadded-up light bulb wrapper from her hands. He found the panel on the wall where the bulb was installed and hit the switch, flinching for an instant as it bathed the veranda in a warm yellow glow.

Life over the next several months was different, though it wasn’t exactly the revolution Anita Chauhan had expected.

The family bought a few simple appliances — a hand mixer, an iron, a small electric stove with one burner. It took less than half an hour to make dinner now that she didn’t have to collect wood or start a fire.

Their solar battery, housed in a plastic case the size of a toolbox, conked out yet again and for once they didn’t bother having it fixed.

Bijender Singh sped up work on a new family house on an outcropping above their current dwelling, drilling power sockets into the concrete walls in each of the three rooms. Instead of dirt floors he installed tiles, the builders’ mechanical saw buzzing as it shaped the pieces.

But they did not buy a TV or the water heater they had hoped for. A surprise hailstorm killed off half the apple crop, erasing most of their profits.

Over time, they saw the electricity supply could be just as unpredictable.

During heavy rains in July and August, the power sometimes went out for days. In September, they spent more than two weeks in the dark. Arun Kant, an official with the state power company, said a fallen tree knocked out a transformer in the forest during the rough weather.

The Chauhans went back to using firewood and kerosene, but their supplies nearly ran out after rockslides blocked the roads. Frustrated, the youngest Chauhan brother, Bharat Singh, threatened to lead villagers on a march to the local utility officer’s house.

Then one day, their lights worked again.

“These electricity officials are extremely corrupt and incompetent,” Bijender Singh said. “In the cities, there are big requirements for power. Here we just want to watch TV or read under a lamp.”

The frustrations in Barnali point to a challenge at the heart of India’s electrification drive: Poor villagers consume little electricity and generate hardly any revenue for utility companies, so companies see little incentive to make rural service more consistent.

“Utilities feel there is no financial case for extending the grid to areas where the ability to pay for electricity doesn’t exist,” said Karthik Ganesan, a research fellow at the Council on Energy, Environment and Water, a New Delhi-based research organization.

“But many surveys indicate rural India does have an appetite to pay for it, because they pay more for services like kerosene. So the question is, are you able to deliver a system that is reliable enough that I am willing to pay.”

Still, even patchy electricity has brought villagers closer.

Many evenings, the Chauhan brothers gather in the clapboard bedroom of their neighbors, the Rawats, to watch TV. The $130 analog model had been the Rawats’ first purchase after the power came.

Anupa Rawat bought a small mixer to make chutneys. Some nights she stays up late knitting by the light of a lone bulb above their doorway.

“We don’t need much more than this for now,” she said. “We managed without machines for all this time.”

The happiest change, she said, was that her two sons now slept at home, in the room next to their parents.

“It’s nice that the whole family stays here,” she said. “In today’s world, who doesn’t want light?”

This story was reported with a grant from the United Nations Foundation.

Follow @SBengali on Twitter for more news from South Asia

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.