Yakutsk is one of the coldest cities on Earth. It’s producing some of Russia’s hottest punk rock

- Share via

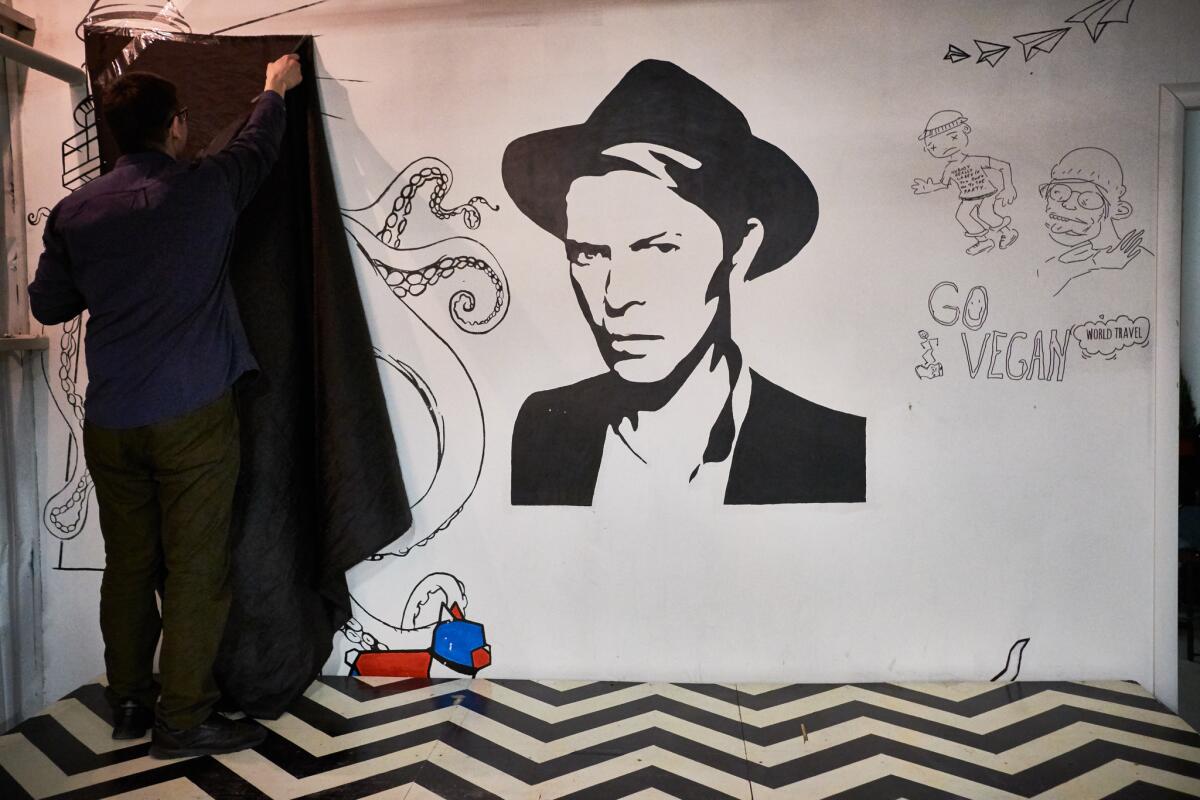

Reporting from Yakutsk, Russia — Vlad Sleptsov stepped onto the small stage of a back-alley bar in deepest Siberia. Stage lights illuminated his spiky, bleached-blond hair.

Shirtless and with his back to the audience, Sleptsov began warming up his guitar with the first chords of Black Sabbath’s “Iron Man.” Slowly, he turned to face the crowd, revealing tattoos scattered across his chest, arms and stomach. The crowd pushed toward the stage.

Outside it was 5 degrees — early spring in this city just below the Arctic Circle. But it was warm inside the Grunge Bar, a converted metal garage once used as a carwash, where Sleptsov and his band, the Name of Your Ex Girlfriend, blasted out songs to a young, sweaty crowd.

Yakutsk is remote, cold and isolated from just about everything else in Russia. The city is some 5,000 miles east of Moscow in the Yakutia region, so wide it stretches across three of Russia’s 11 time zones. The eastern Siberian region is best known for diamonds, gold, oil and permafrost. The first three have contributed substantial revenue to the Russian budget for decades.

Now Yakutsk is becoming known for something else: underground punk bands.

The Name of Your Ex-Girlfriend and half a dozen other Yakutsk punk bands record under their own label, Yunost Severa, or Youth of the North. In recent years, the bands have emerged with a fervor onto Russia’s underground music scene.

“These bands aren’t particularly talented or good,” said Maxim Dinkevich, the founder of Russia’s most widespread underground music fanzine, Sadwave. “But they play raw, like artists who play just for art’s sake. There’s definitely something unique about their … abrasive, violent, weird sounds.”

Sadwave’s website recently ran a review of the bands that rapidly spread across social media sites dedicated to Russia’s underground punk scene.

Isolation and harsh climates, it turns out, are an inspiration for musicians.

“It makes you desperate,” Sleptsov said. “We use that desperation in our songs about life here.”

Cold and remote

Life is difficult in Yakutsk. It’s been recorded as the second-coldest permanently inhabited city in the world. (The coldest is a tiny port city north of Yakutsk called Verkhoyansk.) In the short summers, temperatures can reach 100 degrees. Last summer, a wave of severe forest fires filled the dry, hot air with choking smoke.

It’s not just the harsh climate that makes life in Yakutsk hard for young people, said Katya Mamina, 23, the lead singer of the band Katya’s Tears. It’s the isolation. The great Trans-Siberian Railway across Russia doesn’t go this far north. Plane tickets to Moscow or St. Petersburg, or even Vladivostok on the Pacific Coast, are upwards of $500. In the winter, cars can ply the frozen Lena River like a road. In the summer, the regional roads heave with thawing earth and become muddy and impassible.

Touring isn’t really an option for Yakutsk’s punk bands. “After getting as far as Moscow, there’s usually no money left to go to another city,” Mamina said.

There also aren’t many work prospects for young, restless Yakutians who don’t want to go to the mines or gas fields. Unemployment among people ages 20 to 24 is 74%, according to government statistics. Perhaps not surprisingly, drinking is a pastime. Alcoholism is enough of a problem that the government restricts the sale of alcohol and beer in stores to between the hours of 2 p.m. and 8 p.m.

These bands aren’t particularly talented or good. There’s definitely something unique about their … abrasive, violent, weird sounds.

— Maxim Dinkevich, the founder of Russia’s most widespread underground music fanzine, Sadwave.

50 below

Sleptsov’s band opened with “Touristic Mirage,” a song about an endless drinking binge. It was one of several songs that evening about getting drunk, fighting with loneliness and wanting to escape your hometown when it’s minus 50 degrees outside.

When Katya’s Tears played, Mamina crouched over her tightly held microphone with a yellow baseball cap worn backward and belted out lyrics about passing out in a snowbank.

Crispy Newspaper’s Igor Tsoi sang in a low, garbled voice in the local Yakut language, chastising the authorities for the poverty Yakutian people endure.

To leave or stay

Beneath the angst and the struggle to be an individual are the roots of despair in a country where the government sometimes rewrites history and suppresses dissenting voices.

In the last year, the Kremlin has cracked down on music popular with the country’s youth. Police have shut down concerts under the guise of protecting children or claiming that the performers were violating Russia’s law against “gay propaganda.”

Ignat Barchakov, who started the Name of Your Ex-Girlfriend, said Yakutsk’s bands have stayed off authorities’ radar because their songs aren’t political. At most, they touch on the politics of the day subtly, he said.

“It’s not about Russia; it’s not about the world,” he said. “It’s about ourselves and our experience living in Yakutia.”

Siberian punk bands have a history of stirring the ire of authorities. In the late 1980s, when perestroika, or reconstruction, was opening up some parts of Soviet life, bands such as Civil Defense, from Omsk, became popular across the country. But they paid a price for their anti-establishment lyrics and nonconformist lifestyles. Far away from the big cities of Moscow and Leningrad, Soviet punk bands were targeted by the KGB. Civil Defense’s lead singer, Yegor Letov, an icon of early Russian punk, was sent to a mental hospital.

“The Soviet state wasn’t ready for this kind of pressure, especially from the youth,” said Alexander Herbert, a specialist in late Soviet history and the author of “What About Tomorrow?: An Oral History of Russian Punk from the Soviet Era to Pussy Riot.”

Crispy Newspaper’s lead singer, the 27-year-old Tsoi, said he believes punk shouldn’t just be about the opposite sex or getting drunk. His band performs in the Yakut language to make a statement, he said.

“Real Yakutia starts 60 miles from Yakutsk,” he said. “There is poverty everywhere that you don’t see here.”

Tsoi is from Mayya, a small settlement of about 8,000 people about 45 miles east across the Lena River. In Yakutsk, Tsoi rents a garage on the outskirts of the city with a space heater, a mattress, some speakers and a drum set for when the band comes over.

While the region is part of the Russian Federation, many Yakutians, like Tsoi, see Russia as a foreign country.

“I’ve never even been to Russia,” Tsoi said.

‘A collective of friends’

The Name of Your Ex-Girlfriend started four years ago when Sleptsov, a high school dropout who couldn’t get into music college, and Barchakov met at a party. The pair eventually met up with Tolya Chirayev after rotating through a series of drummers and bassists.

Chirayev, 28, is the drummer in at least four other punk bands. He’s also the vice principal of the Yakutsk City National Gymnasium, where a small, cramped sound room has become the Youth of the North’s recording studio. Chirayev is the label’s de facto producer, manager and mentor to many of the younger players.

“We’re not so much a recording label as we are a collective of friends,” Chirayev said.

The internet has allowed Youth of the North bands to distribute their music online and gain a following through social media.

Last year, members of the Name of Your Ex-Girlfriend and Katya’s Tears went to Moscow and played in some small venues to packed crowds.

“I wouldn’t call them bars, they were more like practice spaces,” Mamina said. “But people knew who we were. That was really a surprise for us.”

It wasn’t like playing at home, though, Sleptsov said.

“When bands in the provinces go play Moscow, they don’t have as much fun as they do at home because all the kids in Moscow are just standing there with their arms crossed and watching the band,” said Herbert, who’s traveled around Russia to find punk scenes. “But in the provincial cities, people are dancing and having fun and the energy is both in the crowd and on the stage.”

“It makes you desperate. We use that desperation in our songs about life here.”

— Vlad Sleptsov, singer with the Name of Your Ex-Girlfriend, on living in Siberia

Inevitably, some of the Yakutsk punks move on. Katya Mamina now lives in St. Petersburg, where she is studying mass communications. After graduation, she wants to make a go at becoming a successful musician. She left behind three members of her band to pursue her dreams.

She loves the adventure of seeing something new, something bigger than Yakutia. But there are days in St. Petersburg, the former home of the czars, when Mamina said she finds herself questioning what it means to be Yakutian and where she belongs. She misses the camaraderie of the Youth of the North collective. She’s still drawn to the artistic inspiration she gets from the hardships here, which have helped shape a unique Yakutian punk identity in an increasingly nationalistic Russia.

“The situation about national identity is really changing now for young people here,” she said. “For me, this is a hard question. I don’t feel Russian, but I don’t feel not Russian.”

It may be a question she continues to ask herself for the rest of her life, she said.

ALSO:

Long before U.S. hipsters discovered it, kombucha was a staple in Russia. It’s making a comeback

Russians are dancing the winter away, often in their underwear. There’s a reason for that

There’s a museum in Russia honoring Boris Yeltsin. Team Putin doesn’t like it

Twitter: @sabraayres

Ayres is a special correspondent.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.