Obama’s summit will take place without most Persian Gulf leaders

- Share via

Reporting from WASHINGTON — Between the lines of a bland communique issued last week by six Persian Gulf states was a warning: If Washington won’t help us roll back aggressive moves from Iran and its allies, we will do it ourselves.

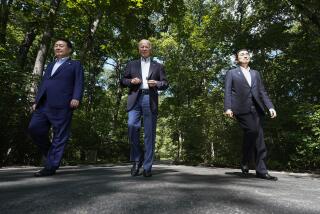

That blunt message will be central to a two-day summit this week between President Obama and the six members of the Gulf Cooperation Council, a gathering that both sides say could yield a historic strengthening of defense ties.

The United States and its oil-rich gulf partners, who have fought as allies in multiple wars, have drifted apart amid the deepening chaos of the Middle East and anxieties over the growing regional influence of their historic rival, Iran.

As the leaders prepare to meet at the White House on Tuesday and at the presidential retreat at Camp David on Wednesday, analysts say senior officials will be satisfied with a partial repair of their fraying diplomatic and security bonds.

“They’re not expecting to settle all issues: They know that’s not going to happen,” said Hussein Ibish, a senior resident scholar at the Arab Gulf States Institute in Washington. “If they can get 70% of the way there, that will feel like 100%.”

In one possible sign of the tensions between the allies, Saudi Arabia announced Sunday that King Salman would not be attending the summit, the official Saudi news agency reported.

Only last week, White House officials said Salman would be present. Although administration officials insisted this was not a sign of the king’s unhappiness with the new commitment the United States is offering, analysts have been warning for some time that Salman could decline to make the trip to signal his dissatisfaction with Washington.

Salman, 79, is in poor health and does not travel frequently. The Saudis will instead send Crown Prince Mohammad ibn Nayif, the interior minister, who has warm relations with U.S. officials.

The leaders of the United Arab Emirates, Oman and Bahrain have also decided to send subordinates, Arab news agencies reported. Sultan Qaboos bin Said of Oman and Sheikh Khalifa bin Zayed al Nahyan, the UAE president, have been ill, and analysts had been predicting that they would send others in their place.

Recent published reports have suggested that the Obama administration would deliver a bounty of cutting-edge weapons such as the stealthy new F-35 fighter jet, and guarantee the gulf states’ safety with a treaty pledging to defend the gulf with U.S. nuclear weapons if necessary.

That’s not going to happen, U.S. officials say.

Instead, the administration will offer to better integrate U.S. support for antimissile, maritime, border and counter-terrorism defenses in the gulf, officials say.

Obama will offer a written pledge reaffirming America’s commitment to defend its gulf allies: Saudi Arabia, Kuwait, Bahrain, the United Arab Emirates, Qatar and Oman. But it won’t be in the form of a legally binding treaty.

In the four years of turmoil that have followed the “Arab Spring” uprisings, the two sides have developed differing perspectives on major issues between them. And they have different goals for the summit.

The Obama administration wants to convince the six states that it remains committed to their security despite its attempts to reach a nuclear deal with Iran that, the White House argues, will ease a major threat and reduce tensions with Tehran.

It wants to show that the gulf states “won’t be sacrificed on the altar of entente with Iran,” Martin Indyk, a former top administration envoy to the Middle East, said last week at a conference sponsored by the Atlantic Council think tank.

The administration wants to mute gulf states’ public criticism of the politically sensitive nuclear deal, which the United States and five other world powers — Britain, France, Germany, Russia and China — hope to complete by June 30.

The six-country diplomatic bloc is offering to ease economic sanctions on Iran if Tehran accepts restrictions aimed at preventing it from obtaining a nuclear weapon.

The gulf states, which have been pushing for a top-level summit with Washington for four years, have different goals.

Beyond the arms and security affirmations, they want to push the United States to do more to roll back Iran’s incursions in Syria, Yemen, Iraq and Lebanon.

They want the administration to do more to unseat Syrian President Bashar Assad, an Iranian ally; to push harder against Shiite Muslim militias in Iran; and to step up efforts against Iranian-sponsored terrorism and the flow of Iranian arms in the region.

They believe Iran is on the march, through allies and proxies. They fear that the nuclear deal will give Iran new legitimacy and boost its support of allied militias by giving it access to more than $100 billion that has been frozen under international sanctions.

In Obama’s unwillingness to bomb Syria two years ago for its use of chemical weapons, his strategic “pivot” to Asia and the Western Pacific and his carefully tailored military campaign against Islamic State, the gulf states see a scaling-back of Washington’s commitment to them.

Some gulf officials continue to press for an upgrade of guarantees such as those extended to the United States’ North Atlantic Treaty Organization partners.

“We are looking for some form of security guarantee, given the rise of Iran in the region,” Yousef Otaiba, the UAE’s ambassador to the United States, said at the Atlantic Council meeting. “We need something in writing … we need something institutional.”

Obama, however, remains adamant about setting limits on U.S. military involvement.

Though he may incrementally increase U.S. efforts in these conflicts, “it won’t be enough for the gulf states,” said a congressional expert, who asked to remain anonymous because of staff rules. “So I expect them to leave dissatisfied.”

The administration and gulf officials are likely to remain divided on another vital subject that will be on the table: how to preserve the gulf states’ stability.

Obama believes the greatest threat to the gulf states is from the swelling population of unemployed and uneducated young people, who may turn to violent extremism and try to topple governments if they can’t find jobs.

“This is a conversation we welcome — in private,” Otaiba said. But the conservative states aren’t expected to accept enough political reform to satisfy the White House.

Partly as a result, the gulf states are signaling that they are ready to lean more on others and to do more by themselves.

French President Francois Hollande was a surprise guest at a meeting of the gulf states Wednesday in Riyadh, the Saudi capital. His invitation was a message of appreciation of France as the Western country that has been the most ready to use force in the Middle East and for its pushing Iran hardest in the nuclear negotiations.

“France, in other words, is the Western state that is closest in thinking to the gulf states, and especially Saudi Arabia — in implicit contrast to the Americans,” Ibish wrote last week on his blog.

France is upgrading its security ties with the gulf states and signing more defense contracts, including a $7-billion sale of 24 Rafale fighter jets to Qatar.

At the Riyadh meeting, the gulf states gave an implicit blessing to Saudi Arabia’s more assertive and interventionist foreign policy.

The new approach, set by King Salman since his accession in January, has been seen most dramatically in Saudi Arabia’s military intervention in Yemen. It is another source of U.S.-gulf friction that will be high on the agenda at Camp David.

Though Washington is providing logistical and intelligence support, it is uncomfortable with the high casualties and what it sees as unrealistic Saudi objectives. U.S. officials have pressured Riyadh to halt attacks on the Iranian-supported Houthi militias and instead seek a diplomatic solution before the conflict widens.

On the eve of a planned humanitarian pause in the fighting, Saudi-led airstrikes targeting weapons storage sites set off a series of loud explosions in Yemen’s capital, Sana, on Monday. Residents streamed from the heavily-populated area, as dark smoke billowed and flames lit up the night sky.

Saudi Arabia has offered to suspend strikes for five days beginning Tuesday to facilitate the delivery of aid to civilians trapped in the fighting. Houthi leaders have agreed to respect the cease-fire.

The Obama administration also has pushed its Mideast allies to do more in their own defense and take the lead in joint military operations — a process that U.S. officials call “offshore engagement” and that critics disparage as “leading from behind.”

But some U.S. officials acknowledge that it’s tough to get America’s Arab allies to do more, without having them go too far.

One Arab official acknowledged the dilemma.

“We’re facing the most serious threats,” said the official, who declined to be identified because of the diplomatic sensitivity of the subject. “If others won’t take care of them, we will have to.”

Staff writer Brian Bennett in Washington and special correspondent Zaid al-Alayaa in Sana, Yemen, contributed to this report.

Twitter: @richtpau

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.