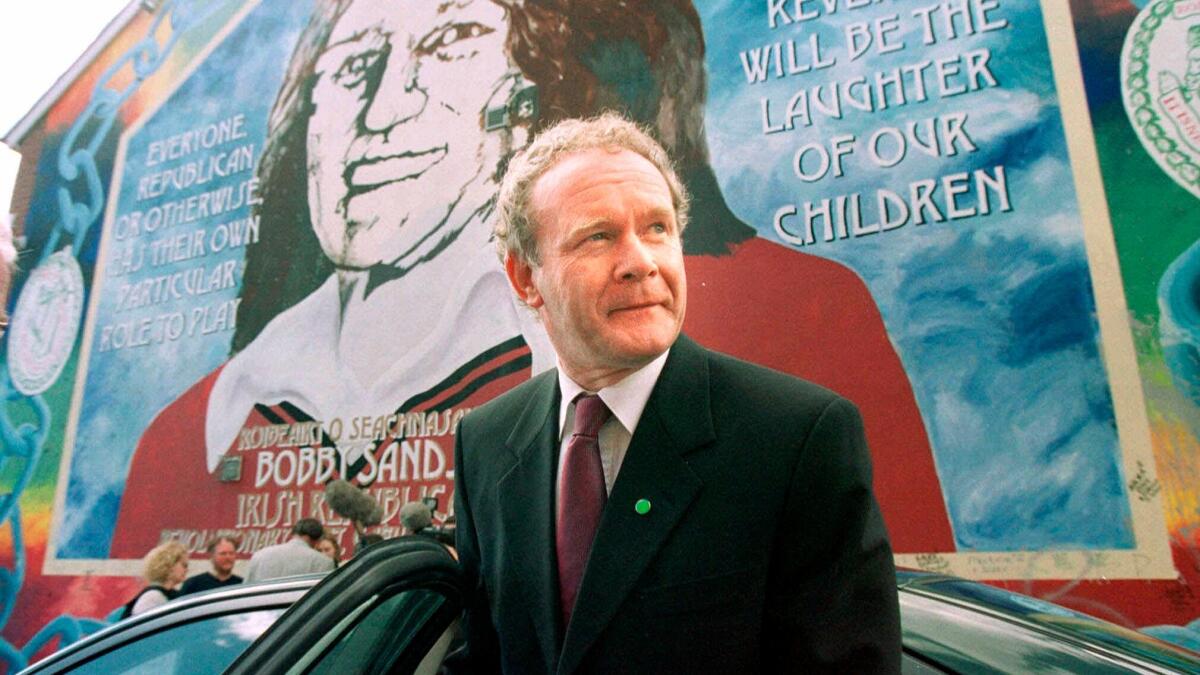

Martin McGuinness, ruthless IRA commander who traded his weapons for peace, dies at 66

- Share via

London — Martin McGuinness, the ruthless Irish Republican Army commander who traded his weapons for politics and later played a key role in the Northern Ireland peace process, has died, leaving behind a conflicted legacy.

Once described as “Britain’s number one terrorist,” the die-hard Irish rebel was accused of overseeing some of the most deadly and devastating attacks on British and Irish soil during the height of the violence between Protestant and Roman Catholic forces.

He took up arms against British soldiers with the stated intention of bringing about the reunification of Ireland through force, and spent several stints behind bars for his links to the paramilitary group.

But after dedicating years to the pursuit of conflict, he chose instead to achieve his goals through diplomacy.

“My war is over,” he said in 2008. “My job as a political leader is to prevent that war and I feel very passionate about it.”

How much blood might be on McGuinness’ hands was unclear, though the IRA killed at least 1,780 people during the height of its violence, making his transformation from combatant to peacemaker all the more remarkable.

Working alongside Sinn Fein’s Gerry Adams, who led the political wing of the IRA, and then-British Prime Minister Tony Blair, McGuinness helped facilitate the historic Good Friday Agreement, which was signed in 1998, bringing peace to the two sides.

Paying tribute to McGuinness Tuesday, Blair said he possessed a “steel” and “determination” which made him an invaluable ally in the peacemaking process.

“The quality of strength and determination that made him such a formidable foe during the armed struggle was also what made him such a formidable peacemaker later,” Blair told the BBC. Former U.S. President Bill Clinton also said that McGuinness’ “integrity and willingness to engage in principled compromise were invaluable” in securing the peace accord.

But news of his death was also met with condemnation and shrugs of indifference from those whose lives were scarred by the IRA during those bloody years.

Lord Tebbit, whose wife was paralyzed by the IRA’s 1984 bombing of the Grand Hotel in Brighton, England, described him as “a coward, a murderer.”

Tebbit said he only hoped that McGuinness was now “parked in a particularly hot and unpleasant corner of hell.”

Colin Parry, whose 12-year-old son, Tim, died in an IRA bombing in Warrington, England, in 1993 also refused to forgive the actions of either McGuiness or the IRA, but did concede that he was a man who sincerely hoped to bring about peace.

“I think he deserved great credit for his most recent life, rather more than his earlier life, for which I don’t think anything in his most recent life can atone.”

Born May 23, 1950, McGuinness grew up in Londonderry, and joined the IRA after dropping out of high school and working as an apprentice butcher in the late 1960s. The Catholic civil rights movement faced increasing conflict with the province’s Protestant government and police; McGuinness said he was drawn to the IRA by the senseless deaths and discrimination he witnessed.

He rose to become Derry’s deputy IRA commander by age 21. McGuinness appeared unmasked at early Provisional IRA news conferences, and the BBC filmed him walking through his Bogside base discussing the IRA command structure.

In 1972, during Northern Ireland’s bloodiest year, McGuinness joined Adams in a six-man IRA delegation flown by the British government to London for secret face-to-face negotiations during a brief truce. Those talks went nowhere. McGuinness went back on the run until his arrest in the Republic of Ireland near a car loaded with 250 pounds of explosives and 4,750 rounds of ammunition.

His later transition into politics was a bitter pill for some members of his own community to swallow, and he faced threats from dissident republicans. Still, he managed to forge a way forward, working at the heart of the new Irish power-sharing government, serving as education minister and later deputy first minister.

There he built a strong, yet unlikely, friendship with First Minister Ian Paisley of the Democratic Unionist Party and their obvious bond earned them the nickname “the Chuckle Brothers.” When Paisley died in 2014, McGuinness offered a warm tribute.

“Past history shows that we were political opponents, but on this day I think I can say without fear of contradiction that I have lost a friend.”

In 2012, McGuinness also famously shook hands with Queen Elizabeth II during her visit to Northern Ireland — a symbolic political gesture that would have seemed inconceivable decades earlier. Two years later he also gave a toast to the queen during a banquet at Windsor Castle.

The queen sent a personal condolence letter to McGuinness’ wife on Tuesday, and British Prime Minister Theresa May said that although she could never “condone the path he took in the earlier part of his life,” McGuinness had played a “defining role in leading the republican movement away from violence”.

McGuinness spent the majority of his life in the spotlight and only withdrew from politics two months ago, announcing he would not stand for reelection to the Northern Ireland Assembly. He gave a tearful farewell speech where he told supporters that he was physically unable to continue his role.

“It breaks my heart,” he confessed.

In recent weeks, there had been press reports that his health had deteriorated, and it was confirmed Tuesday that he died at the age of 66 in his hometown of Londonderry of a rare genetic disease.

He is survived by his wife, Bernadette, two daughters and two sons.

Boyle is a special Times correspondent based in London.

The Associated Press contributed to this story.

ALSO

Robert Silvers, founding editor of the New York Review of Books, dies at 87

Billionaire philanthropist David Rockefeller dies at age 101

Jimmy Breslin, legendary New York City columnist, dies at 88

UPDATES:

3:15 p.m.: This article has been updated with Times reporting.

9:59 a.m.: This article was updated with additional details, background and reaction.

This article was originally published at 12:05 a.m.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.