Tobacco companies see Africa as fertile ground

- Share via

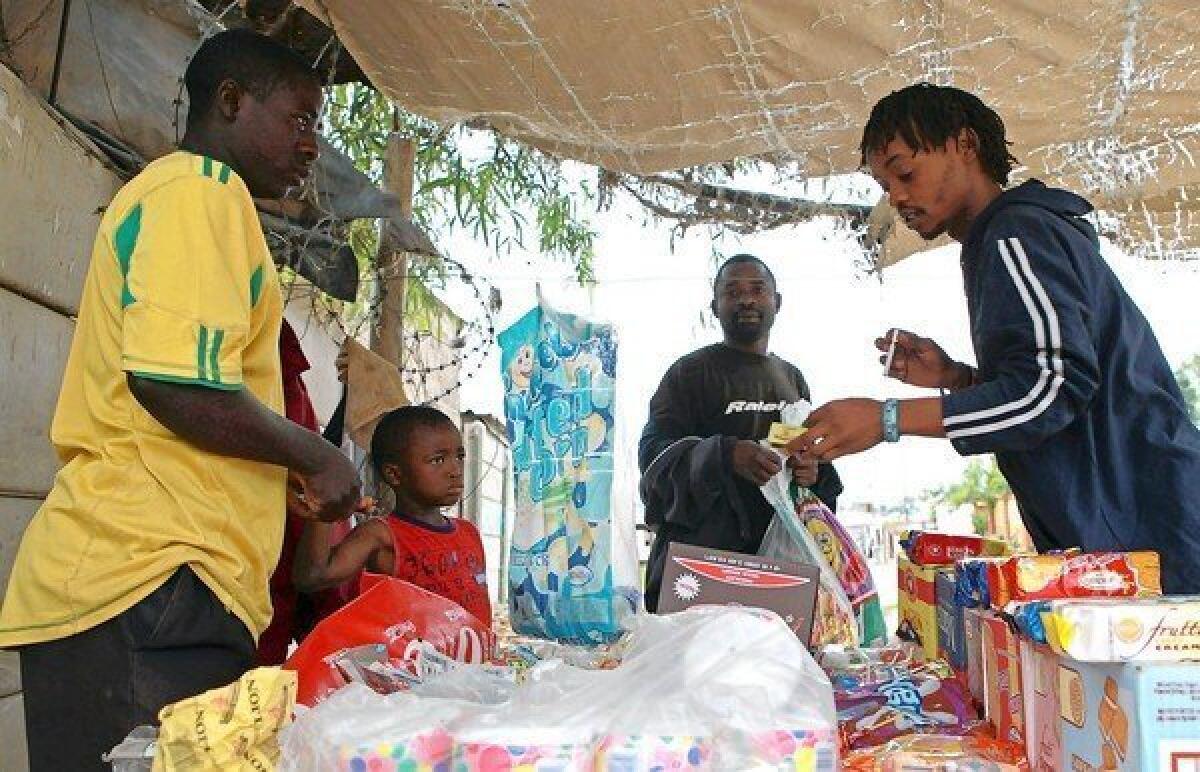

DIEPSLOOT, South Africa — On the sunny side of a dusty township street, next to the metal gates of a school, Lucas Moyana’s little shop is just a board propped on four plastic crates like a child’s lemonade stand. For a couple of coins, he sells being cool, sells being free.

A schoolboy in uniform hurries up, barely glancing at the cookie packets, lollipops and candies, grabs a Dunhill cigarette from a red box, puts a match to it and drops 22 cents on the table before hurrying away.

Moyana is at his stand, just a few yards from the school gates, most days from 5 a.m. to 7 p.m.

Asked why he set up next to the school, he looks awkward. “I just decided this was a good spot,” he says vaguely, basking in the hot spring sun. Every few minutes, a customer tosses some change onto his table, plucks a cigarette, lights it.

Africa is Big Tobacco’s last frontier, and companies are conquering the continent stick by stick. Even a child can afford the cost of a single cigarette, 16 cents for Moyana’s cheapest brand.

South Africa has some of the toughest regulations on the continent. Unlike in the United States, though, where the sale of packs with fewer than 20 cigarettes is prohibited, selling cigarettes single, or “one-one,” is not specifically banned here.

It’s twice as profitable for Moyana to sell cigarettes one-one. He doesn’t even bother to display sealed packs. And although it is illegal here to sell cigarettes to anyone younger than 18, he doesn’t turn them away.

Tobacco use is declining in the developed world. It’s reached a plateau in the strongest market, Asia. But it is growing in Africa, because of the continent’s booming population and rapidly expanding middle class.

“This is a major battleground,” says Yussuf Saloojee of South Africa’s National Council Against Smoking. “The African population is very young. If they can hook customers now, they’ve got customers for the next 40 or 50 years. So the prospects of an increasing market share are very good.”

***

In Diepsloot, there’s a way of walking that shows you almost own the township. Johnnie Thobejane’s pace is quiet but powerful, and so slow that time seems trapped in every step.

At 20, he and his friends are still making their way through school, and they buy lollipops sometimes, when they don’t mind looking like kids. But a cigarette costs the same as a lollipop, so when they have a few dimes, they mostly buy cigarettes from Moyana’s stall.

Thobejane has been smoking since he was 13 and says all his male school friends do as well.

“All of them, they smoke,” he says with a laugh. “It’s like the smoking department.”

In South Africa, tobacco advertising is banned, but Thobejane and his friends don’t need a TV commercial.

“It keeps me rollin’, keeps me walkin’. It’s cool,” says Thobejane, speaking like an American hip-hop artist.

He goes through six cigarettes a day, because that’s what he can afford.

Across the continent, young men like Thobejane are at the heart of tobacco companies’ campaign to capture the African smoker. Few African women smoke, but 20% to 30% of men in many African countries do, more than half of them younger than 35, according to a 2011 World Health Organization report. In South Africa, 35% of men smoke, one of the highest rates in sub-Saharan Africa.

African activists’ battle to protect the young echoes those fought and won in the United States and Europe decades ago. The tobacco industry went to South Africa’s top court recently to defend its constitutional right to advertise cigarettes, and lost.

“The market is so severely restricted that you can’t really aggressively market the product. Restrictions are getting more and more strict, right across the continent,” says Francois van der Merwe, chairman of the Tobacco Institute of Southern Africa.

The potential market in Africa is large, says Evan Blecher, an economist with the American Cancer Society’s International Tobacco Control Research Program.

“You don’t have a lot of smokers now, which means there’s a lot of growth potential,” he said. “In Africa, population growth is rapid. Over the next 20 years, the one region where smoking prevalence is going to rise under any circumstances is Africa.”

A 2011 study by the University of Michigan found that without more action by African nations to discourage smoking, the percentage of smokers will rise from an average 16% to 22% by 2030, a massive increase given U.N. predictions that sub-Saharan Africa’s population will rise by half a billion, to 1.3 billion, by then.

“Twenty years ago, the industry wasn’t interested in Africa because they were still seeing considerable growth in other markets. As they’ve been pushed out of America, Australia, Europe, they’re moving on to the next lowest-hanging fruit,” Blecher says. “With the resources that they have and the experience they have, they will be successful if nothing’s done.”

South Africa saw a significant decline in smoking from the mid-1990s until the early 2000s, when tobacco taxes increased. But since then, activist Saloojee says, efforts to cut smoking have stalled, partly because taxes have not risen significantly since then. A 2009 WHO report said South African taxes on cigarettes were 45%, compared with 55% in Kenya and 70% or 80% in many developed countries.

Despite the statistics showing a long-term decline in smoking, sellers in Diepsloot say the number of buyers in the neighborhood is steadily growing, including among teenage boys, the group most likely to give up smoking when prices rise, analysts say. Tobacco industry representatives say their surveys show a steady increase in smoking in South Africa, mainly because of cheap illicit cigarettes.

Saloojee says the South African government, unlike those of many other countries on the continent, has imposed exemplary regulations limiting tobacco use. But he says it has failed to spend money to educate the population about the dangers of smoking.

The reason Africans have traditionally smoked less is because they have less disposable income, Saloojee says. “That makes a very rosy picture for the tobacco industry. As we get economic prosperity in Africa and disposable income rises, the ability of low-income people to increase smoking is there.”

In South Africa, smoking will soon be banned inside public places and within five yards of any doorway, but in Diepsloot’s bars and home taverns, known as shebeens, no one expects it to make a lot of difference. Tobacco companies and free-market advocates say the law will be impossible to police.

***

Diepsloot is an old township of about 350,000 people, many living in tin shacks, not far from one of Johannesburg’s newer walled communities of expensive homes.

Between the township’s box-like brick houses and higgledy-piggledy shacks, bright little street cafes promise the best food on the block. Dented commuter minibuses ply the streets constantly, music blaring from their windows.

A butcher in red overalls strides up to Moyana’s stand, in a snatched break from cutting up animal carcasses.

Eyes darting around, he grabs a couple of locally made Sharp cigarettes at 16 cents apiece, lights up and inhales deeply, eyes half closed.

“I buy Sharp because it’s cheap,” he says, hurrying back to the butchery.

Moyana, the cigarette seller, has never tried smoking. But his one-one sales feed his wife and two children.

“I don’t feel so good about selling cigarettes, but after all, I need to eat,” he says. “And unfortunately, cigarettes sell. I think the number of people smoking has gone up. The way I see it, most people do smoke. People are constantly buying cigarettes.”

Johnnie Thobejane, with his six cigarettes a day, has all the breezy optimism of a young smoker. He says plenty of township children emulate him and his friends.

“These days, they start smoking at 10 or 12,” he says. “They see us smoking. They all want to be like us.”

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.