In Egypt, Hillary Clinton offers support for Islamist president

- Share via

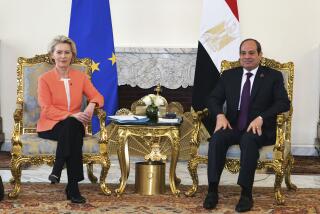

CAIRO — U.S. Secretary of State Hillary Rodham Clinton met for the first time Saturday with new President Mohamed Morsi in a fresh push to strengthen U.S.-Egyptian relations as the country enters an era of unpredictability in which an Islamist leader is clashing with a secular military over control of the nation.

Clinton’s talks with Morsi signaled a historic shift from the days when U.S. diplomats visited President Hosni Mubarak, a stalwart American partner on countering terrorism and preserving Egypt’s peace treaty with Israel. With Mubarak toppled by popular revolt last year, Washington is recalibrating its approach as it deals with a freely elected president suspicious of American designs on the Middle East.

Egypt’s intensifying power struggle threatens to upend its fledgling democracy, and the dilemma Clinton faced was starkly apparent: She showed her support for Morsi but on Sunday was expected to meet with Field Marshal Mohamed Hussein Tantawi, the country’s top military commander, who has rebuffed pressure to cede authority.

“I have come to Cairo to reaffirm the strong support of the United States for the Egyptian people and their democratic transition,” she said. “We want to be a good partner and we want to support the democracy that has been achieved by the courage and sacrifice of the Egyptian people.”

The trip by Clinton to the Arab world’s most populous state unfolds as the Obama administration is moving to keep pace with months of regional upheaval. Egypt has been a key to U.S. policy since the 1970s, but there is sharpening concern in Washington that new Islamist leaders in Tunisia and Egypt will gradually chart a different course even as they seek American aid and investment.

The pivotal moment was underscored when Clinton met Morsi, a U.S.-educated engineer who ran as a candidate for the Muslim Brotherhood, in the presidential palace. The Muslim Brotherhood had been outlawed by Mubarak for decades, and American officials had refused to publicly meet with its members.

Morsi told Clinton, “We are very, very keen to meet you and happy that you are here.”

Egypt is consumed with economic problems, and its foreign policy is not likely to change dramatically in the short term. Cairo has promised to respect its 1979 peace treaty with Israel, although Morsi has suggested it may be reevaluated later. The new president is under pressure from ultraconservative Islamists to improve ties with Palestinians and draw a harder line against Israel.

Clinton emphasized America’s support for the peace treaty. Egyptian Foreign Minister Mohamed Kamel Amr, who stood beside Clinton at a news conference, said, “Mohamed Morsi has repeatedly announced on all occasions that Egypt respects all peace treaties that Egypt is a party to as long as the other party also respects them.”

The battle between Morsi and the military has the United States in a predicament that critics say is rife with irony. Washington is urging a democratic transition and for Morsi’s vision of political Islam to respect civil liberties. At the same time, the U.S. is giving the Egyptian military, which has been subverting the nation’s democracy by disbanding the parliament and limiting Morsi’s powers, more than $1.3 billion in annual aid.

Clinton commended the military for “representing the Egyptian people” during the revolution, unlike the Syrian army’s daily assaults on civilians that have left thousands dead as President Bashar Assad clings to power.

“But there is more work ahead,” she said. “And I think the issues around the parliament, the constitution have to be resolved between and among Egyptians. I will look forward to discussing these issues tomorrow with Field Marshal Tantawi and in working to support the military’s return to a purely national security role.”

She added that the U.S. would forgive $1 billion in Egyptian debt and provide $280 million for economic development.

The strategic relationship between Cairo and Washington has been further complicated by the case of 16 American civil society workers accused of financial and other crimes over democracy-building programs in Egypt. The politically charged case, which began unfolding late last year, marked a low point in relations, especially after Egyptian authorities portrayed the Americans as spies.

The most recent Pew poll in the country found that 76% of Egyptians have an unfavorable view of the Obama administration. Many Egyptians see America as either an interloper or as a nation that promises democratic ideals until they interfere with U.S. national interests.

The same poll found that 60% of Egyptians want the laws of their government to “strictly” follow the Koran, another indication of America’s thinning influence. Protesters, including Christians, demonstrated in front of the U.S. Embassy and the presidential palace Saturday against closer relations between Washington and Morsi. Christians fear that an Islamist-controlled government would curtail civil liberties.

“We believe America shares a strategic relationship with Egypt, far outnumbering our differences,” Clinton said at the news conference.

Special correspondent Reem Abdellatif contributed to this report.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.