HIV among black women in 6 cities far exceeds national average

- Share via

African American women in six U.S. cities are becoming infected with HIV at a rate five times the national average for black women, and closer to the rates of some African countries, according to a new study.

Researchers at Johns Hopkins University and around the country who made the findings suspected the rates were relatively high in these “hot spots” that have battled the epidemic for decades, but the numbers still came as a surprise in a field that tends to focus more on black and gay men.

The researchers found that in Baltimore; Atlanta; Newark, N.J.; New York City; Raleigh-Durham, N.C.; and Washington, the annual rate of infection was 24 per 10,000 black women. Nationally, the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention reports that black women become infected at a rate of 5 per 10,000.

The rate in Congo is 28 per 10,000.

The study was conducted with funding from the National Institutes of Health by researchers who are part of a national consortium called the HIV Prevention Trials Network. The data were presented March 8 at the 19th annual Conference on Retroviruses and Opportunistic Infections in Seattle.

Baltimore declared HIV a public health emergency in 2002, but the numbers of infected people continue to rise, particularly among at-risk groups, including IV drug users and gay and bisexual men.

Dr. Patrick Chaulk, assistant commissioner for HIV and STD services in the Baltimore Health Department, said a large share of the city’s resources to combat HIV go to men because they make up two-thirds of new cases in the city. Nationally it’s about three-quarters, according to the CDC.

But the city and partners at the state and in academic and nonprofit circles haven’t forgotten the women, Chaulk said. He cited programs aimed at drug users and sex workers, among others.

Every week, one city project sends a van with health workers to the Block, Baltimore’s red-light district. The workers have built trust among the people there, and not only test for HIV and other sexually transmitted diseases but also offer reproductive health services, needle exchanges and assistance in securing health insurance and housing.

Through the program, the city reported testing 4,660 women last year for HIV, including 3,362 African American women. About seven were found to be positive for infection and referred for treatment.

The new study underscores the urgency in addressing the problem, said Dr. William A. Blattner, chairman of the City’s Commission on HIV/AIDS Prevention and Treatment, which developed the Baltimore plan to reduce infections.

About the black women in particular, he said, “HIV continues to impact our most vulnerable and marginalized, in particular economically disadvantaged women whose risk is compounded by gender inequality and potential barriers to substance-abuse interventions.”

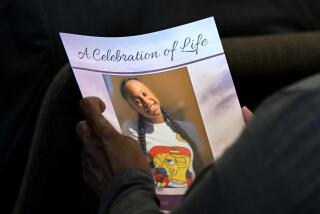

Reaching those women won’t be easy, said Patrice Henry, a patient advocate at Johns Hopkins who was diagnosed with HIV in 1995.

Many women put off being tested because of the stigma still associated with HIV and AIDS, Henry said. They fear telling family and partners. Many don’t have insurance.

“Women also tend not to put their medical concerns first,” she said. “They either think this won’t happen to them or they still find it a sensitive issue to discuss.”

A single 59-year-old living in Baltimore, Henry tells her story to women newly diagnosed with HIV who come to Hopkins for treatment. She shows them they don’t have to be scared of dying, or of living with the virus.

She tells them how she was a professional who never used drugs and was particular about the men she dated. It was nearly impossible for her to believe her diagnosis.

By the time she learned that she had been exposed to HIV, she had already developed AIDS and lost much of her body weight. She was given just a few months to live. Her mother was sitting in the city clinic’s waiting room, and Henry’s first thought was how she would tell her.

But Henry had the doctors explain her treatment to her and her mother. She stuck with the drug regimen, adopted a better diet and has been healthy for 17 years.

Now, she said, she hopes this new study will show how big the problem has become, and maybe persuade more women to get tested and treated.

“We as women need to look after ourselves,” Henry said.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.