A leftist populist could be Mexico’s next president — in part because of corruption allegations against a rival

- Share via

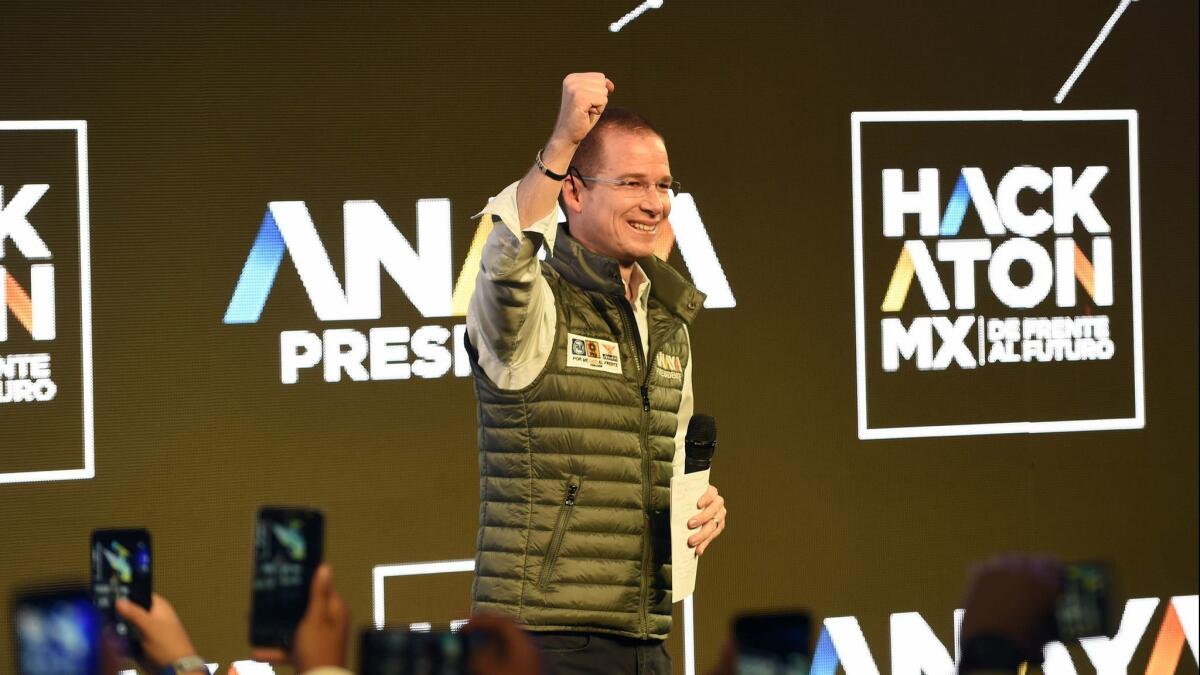

Reporting from Mexico City — Standing before a roaring crowd in Mexico City at the official launch of his presidential campaign, candidate Ricardo Anaya seethed with anger.

“In the last weeks … there have been all kinds of lies,” he said. “From here on we tell the government and the authors of this dirty war that the more resistance we face, the more force we’ll take off with.”

Mexico’s election campaign officially opens this weekend, freeing the four candidates who have qualified for the July 1 ballot to register with the government and start spending heavily on advertisements. But the race — and the drama — have been heating up for months.

Back in November, polls had Anaya tied for first place with leftist populist Andres Manuel Lopez Obrador, a three-time presidential candidate and former mayor of Mexico City who is one of the country’s best-known political figures. Trailing them were Margarita Zavala, the wife of former president Felipe Calderon, and José Antonio Meade, from Mexican President Enrique Peña Nieto’s Institutional Revolutionary Party.

Anaya, a bespectacled former senator from the center-right National Action Party, had ascended quickly, thanks in part to his scathing criticism of Peña Nieto and his risky pledge to investigate allegations of graft by the president and his party.

Until the smear campaign began.

In February, Mexico’s attorney-general, a Peña Nieto appointee, announced he was investigating a property deal involving Anaya, saying the candidate was suspected of laundering money.

Independent investigations into the deal have concluded Anaya likely broke no laws when he bought and sold a plot of land in an industrial park in his home state of Querétaro. A group of public intellectuals — not all of whom are Anaya supporters — signed a letter imploring the government to stop politicizing law enforcement.

But the investigation has continued, staining Anaya’s image as an anti-corruption crusader and significantly reshaping the race. As support for Anaya has slipped from 30% down to 24%, Lopez Obrador has surged. He now has a double-digit lead over Anaya, with 42%.

The impact of the investigation on Anaya’s campaign shows what an important issue corruption is for many Mexican voters, who are incensed after a seemingly unending string of corruption scandals involving governors, cabinet ministers and other allies of Peña Nieto. A recent poll by the Reforma newspaper found that 47% of voters “would never vote” for his PRI party or its candidate, Meade.

Analysts believe Lopez Obrador has surged in part because voters view him as a clean candidate who has not been targeted by corruption allegations. They have flocked to him in large numbers despite warnings from the right that his economic proposals could lead Mexico toward a fate akin to Venezuela’s.

While his opponents have sought to paint Lopez Obrador as a reincarnated Hugo Chavez, the socialist who ruled Venezuela autocratically until his death in 2013, his politics look more like those of former U.S. presidential candidate Bernie Sanders.

Lopez Obrador has proposed rolling back or modifying efforts pushed by Peña Nieto to open the energy sector to foreign investment, and he has criticized the North American Free Trade Agreement, which is currently being renegotiated with the United States and Canada.

While Mexican markets have greeted his rise warily, many voters appear happy to risk uncertainty, said Carlos Bravo Regidor, a political analyst and a professor at CIDE, a public research center in Mexico City.

“Mexicans want change, and anger is trumping fear,” Bravo said. “This election is not about platforms, or issues, or even experience. This is about who has the credibility to make change.”

Bravo said Lopez Obrador has been softening some of his more controversial stances, which also helps.

“I guess he has learned,” Bravo said. “He’s clearly coming to terms with the fact that Mexican voters are more conservative than he would like.”

One place where Lopez Obrador has been tamer this time around is on the issue of corruption. In a recent interview, he said he would tackle corruption, but would not spend energy prosecuting Peña Nieto or his allies. “I am not going to put the president in jail,” he said.

Those kinds of promises have led some to question whether Peña Nieto’s party targeted Anaya in part because it fears him more than Lopez Obrador. Some have even suggested that there may be an alliance between Lopez Obrador and the PRI.

Bravo said he thinks Lopez Obrador is just playing it safe.

“As a candidate, he has more to lose than to win,” Bravo said. “Maybe Peña Nieto and Lopez Obrador just realized they don’t have a lot to gain in fighting each other.”

Lopez Obrador has not spoken out against the investigation into Anaya, even as the attorney general in the investigation, Alberto Elías Beltrán, has come under fire.

The Anaya case isn’t the first time Beltrán has been accused of acting more like a political operative than a prosecutor.

In March, Beltrán opted not to file money-laundering and tax fraud charges against César Duarte, a former PRI governor from the state of Chihuahua, despite ample evidence that Duarte had diverted state funds.

Last year, Beltrán fired the investigator looking into suspected bribes paid to the Brazilian construction firm Odebrecht by Emilio Lozoya, a Peña Nieto ally who worked on his 2012 presidential campaign. A federal judge recently suspended the inquiry.

To read this article in Spanish, click here

Twitter: @katelinthicum

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.