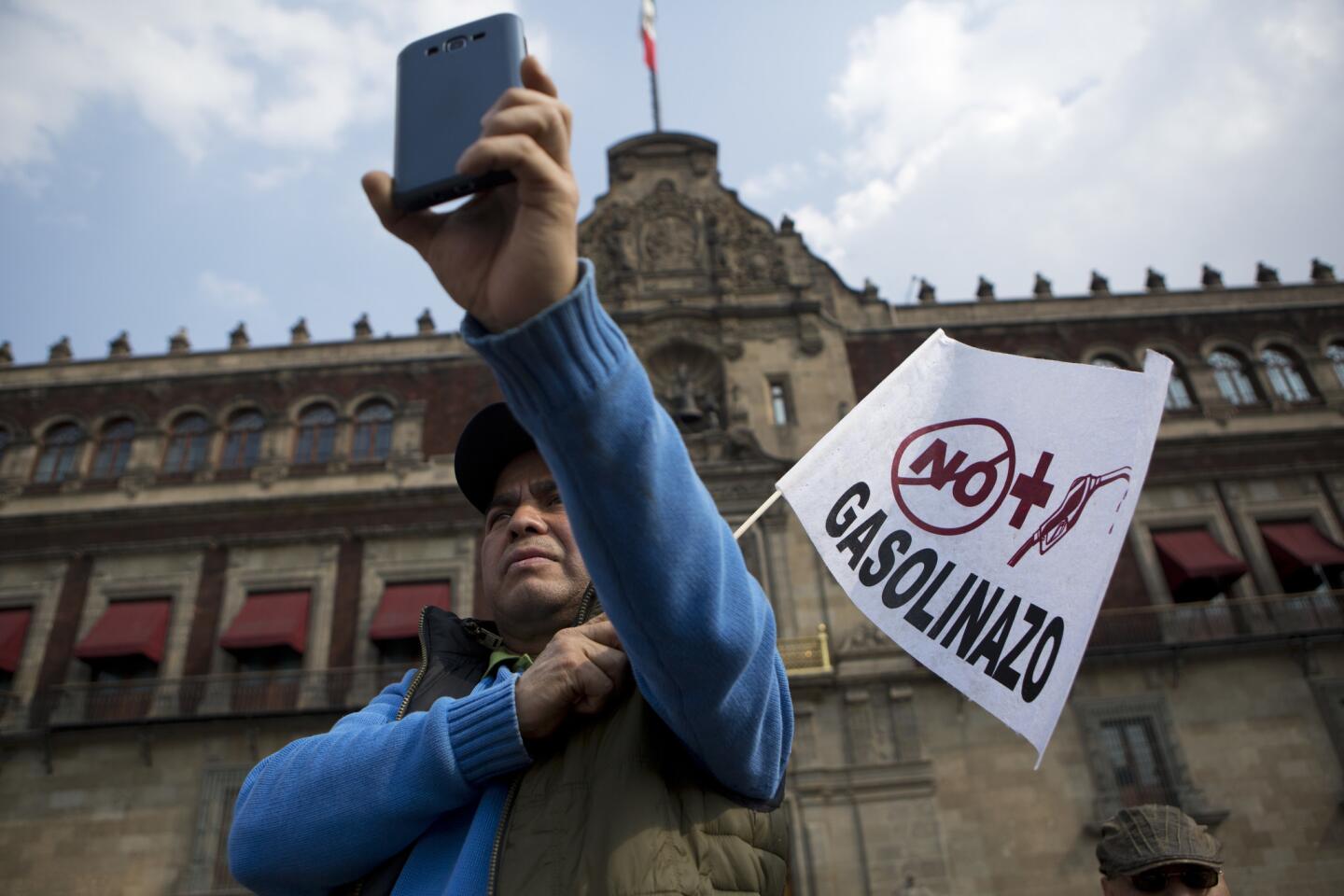

Protests erupt across Mexico over a sudden spike in gasoline prices

On Dec. 31, a gallon of standard-grade unleaded fuel cost roughly $2.60. On New Year’s Day, as a new policy took effect, it jumped more than 14% to about $2.95.

- Share via

Reporting from Mexico City — The bus packed with holiday travelers ground to a halt. Up the highway, on the outskirts of Mexico City, protesters were blocking the lanes, brandishing sticks, burning debris and waving banners that read: “Enough!”

“It’s chaos,” said the bus driver, looking out at a traffic jam that extended as far as he could see.

An hour passed, then five. Passengers were getting hungry. From the windows, they could see travelers who had abandoned their vehicles and were dragging luggage along the dark highway.

The blockade — one of at least 21 that brought traffic to a halt across Mexico on Monday — was staged in response to a sudden hike in gasoline prices brought on by a new government policy of deregulation.

On Dec. 31, a gallon of standard-grade unleaded fuel cost roughly $2.60. On New Year’s Day, as a new policy took effect, it jumped more than 14% to about $2.95. The price of premium fuel rose by as much as 20%.

The protests began after Jesus Zambrano of the leftist Democratic Revolution Party and other opposition leaders called on Mexicans to oppose the hikes by staging a “peaceful revolution.”

On Tuesday, blockades were still snarling traffic on some highways, and authorities were on the hunt for several people accused of hijacking a fuel tanker near Mexico City and siphoning off gasoline.

The state oil giant Pemex called on the organizers of the blockades to cease their activities, warning in a statement Tuesday that “if these blockades and aggressions continue, the supply of gasoline and diesel to the population will be seriously affected.”

For decades, the government had set fuel prices, often kicking in a healthy subsidy. Pemex was nationalized in 1938 and was long a symbol of Mexican pride and autonomy. But it has become a source of scandal in recent years, with some Pemex officials facing charges of corruption.

Deregulation of gas prices, which was announced Dec. 27, is part of a larger effort by President Enrique Peña Nieto to end the state monopoly of the oil industry. The overhaul allows foreign companies to begin oil exploration in Mexico, and later start importing and distributing gasoline there.

The president promised at the beginning of the energy sector overhaul that fuel prices would go down, not up.

Many economists say they believe deregulation will benefit the economy and consumers in the long run. But the sudden change in gas price policy comes at a difficult moment, coinciding with rising world oil prices and the peak holiday travel season as well as rising inflation, a steep decline of the value of the peso against the dollar and U.S. President-elect Donald Trump’s threats to pull out of trade deals and slap taxes on imports from Mexico. Some economists suggested the deregulation was timed to give the Mexican government a much needed infusion of cash.

The Mexican economy took another hit Tuesday as Ford announced it is cancelling plans to build a new $1.6-billion factory in Mexico, investing $700 million in Michigan instead.

“It’s a perfect storm,” said Jorge Piñon, an energy expert at the University of Texas in Austin. “When you compare the cost of gasoline with the average salary in Mexico, versus in the U.S., it costs a lot more, so the increase in cost has a much a higher impact on them.”

A Bloomberg study of 59 countries found that Mexicans, along with South Africans, spend the largest portion of their incomes on gasoline — and nearly twice as much as Americans.

Structural problems with Mexico’s oil refinery and distribution system have compounded the problems, leading to fuel shortages at some gas stations in recent days and spawning a black market for fuel in some states, Piñon said.

“They don’t have the capacity to meet demand,” he said.

Pemex, which has been forced to import oil because its refineries cannot process Mexican crude oil quickly enough, has seen its oil imports from other countries bottlenecked at crowded Mexican ports.

Mexico’s oil pipelines have also been hit by an increase in thefts. More than $1 billion in gasoline is stolen by criminal networks each year, the government has estimated.

Some political analysts speculated that the controversy could benefit the opposition parties hoping to take the presidency in the 2018 elections.

Ricardo Anaya, president of the National Action Party, used the controversy to criticize Peña’s energy reforms for coming too late. He blamed a “lack of investment in strategic areas that today make it necessary to import most of the gasolines we consume in the country.”

Many Mexicans are worried that rising transportation costs will drive up the cost of everything, including food. Even those stranded by the blockades on Monday night were sympathetic to the cause. On the bus stranded on the way to Mexico City, the driver lamented Mexico’s economic fortunes as passengers shared loaves of bread and passed around a single bottle of Coke.

“Everything is going up, the price of tortillas, the price of beans, and it’s going to rise even more,” he said.

“They just better not touch the price of beer!” someone in back responded.

“President Peña,” one woman cried out. “Where are you?”

Cecilia Sanchez in the Times Mexico City bureau contributed to this report.

Twitter: @katelinthicum

ALSO

Ford cancels Mexico factory and will invest in Michigan in ‘vote of confidence’ for Trump plans

Quake swarm near the California-Mexico border gets scientists’ attention

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.