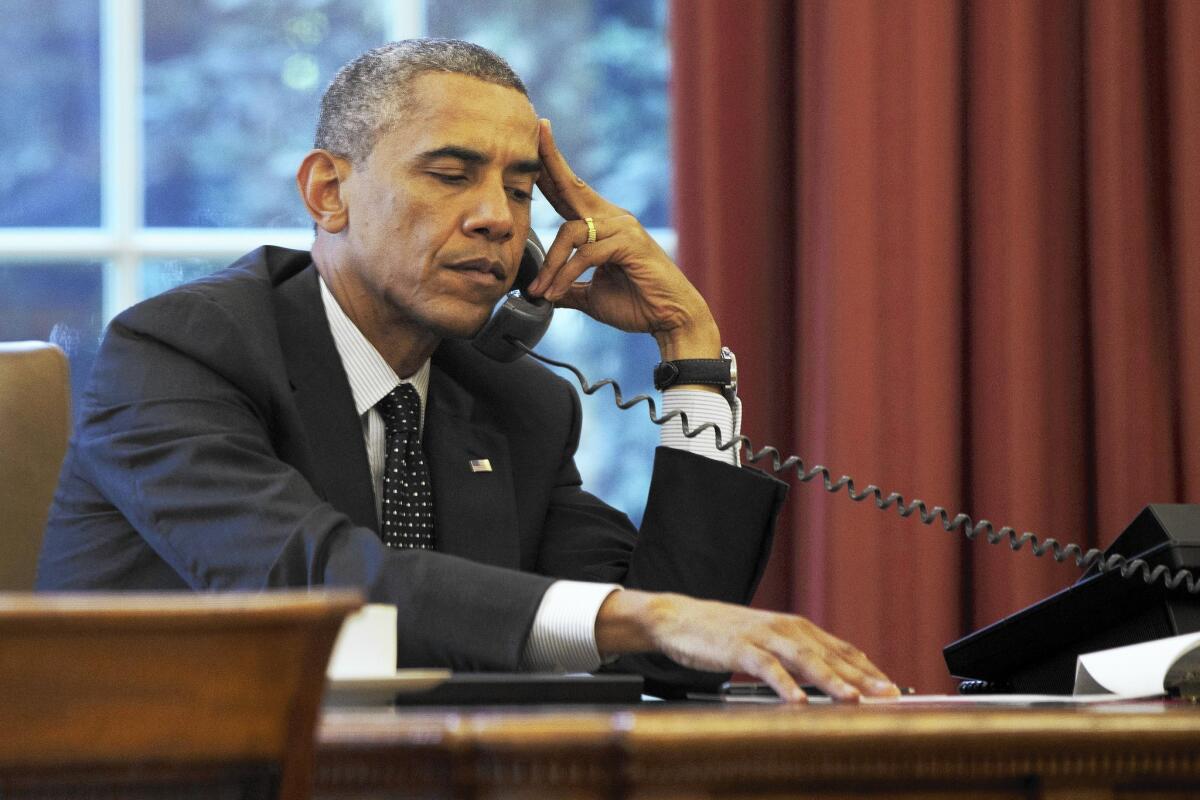

Analysis: Obama returns to the quagmire he exited in Iraq

- Share via

Reporting from Washington — For three years, President Obama has declared himself the man who closed the door on a dark decade of U.S. war in Iraq. Now he has opened the door again.

Other than insisting no U.S. combat troops will return to Iraq, Obama’s advisors outlined few clear limits and no definitive end to America’s latest military mission, which began Friday with airstrikes against Sunni militants and drops of humanitarian aid. Given Obama’s stated reluctance to use military force in Syria and other hot spots, the White House faced pressure to explain why Iraq was different, what airstrikes would achieve and whether Obama was launching a new phase of an old war.

“I see this as a watershed event,” said retired Army Lt. Gen. David W. Barno, the top commander in Afghanistan from 2003 to 2005. “Now that we are using lethal force in Iraq, that’s a huge bridge to cross, and it’s very difficult to get back across once you are over it.”

The president for months resisted taking that step. In June, Obama began sending hundreds of advisors to Iraq to help train and supply government security forces under siege from the Al Qaeda offshoot known as Islamic State. Obama opted against airstrikes, aides said at the time, at least until Prime Minister Nouri Maliki’s authoritarian government instituted democratic reforms.

Behind the scenes, however, the U.S. factories that produce Hellfire missiles began “working seven days a week in order to meet the need and push them out to Iraq,” a senior administration official said. Both manned and unmanned surveillance aircraft and satellites provided near round-the-clock intelligence on Irbil, the Kurdish regional capital, and other key areas.

Then last Saturday, Islamic State fighters launched what U.S. officials called a sophisticated and multipronged attack with armored vehicles and artillery across a broad swath of northern Iraq. By Wednesday night, the militants launched assaults that raised fears of a siege on Irbil and the White House was prepared to act.

The U.S. is flying armed drones and fighter jets over the approaches to Irbil, looking for targets to hit, officials said. As long as the militants can be kept out of major cities, the air campaign can degrade their strength with targeted strikes against vehicles and heavy weapons that are relatively easy to hit in the open, military officials said. That would give Kurdish fighters in the north, and the Iraqi army closer to Baghdad, time to regain their footing.

But the militants are likely to respond by dispersing forces to avoid the U.S. bombs. If they start losing equipment and taking casualties, they may pull back. At a minimum, U.S. officials say, continued airstrikes will delay or deter further advances.

Douglas Ollivant, a retired Army officer who served in Iraq and a former National Security Council official under Obama, said keeping the U.S. military involvement limited was possible because the Islamic State had shown little capability to take control of Irbil or Baghdad. Others weren’t so sure. Some critics said the White House could have simply ordered Americans to leave Irbil, rather than launch airstrikes, just as it evacuated the U.S. Embassy in Tripoli, Libya, last month as fighting surged there.

Some experts warned that “targeted strikes” would prove ineffective. Stephen Biddle, a defense expert at the Council on Foreign Relations, said pinprick bombings have “zero meaningful chance” of ending the widening sectarian war in Iraq. Absent a clear defeat of the militants, Obama may face pressure to do more and more. “The mission creep and quagmire risk is very real,” he said.

If the militants, who are believed to have thousands of fighters, continue to make gains on the ground or shift to another part of Iraq, the U.S. could face pressure to widen the air campaign, or even to put U.S. personnel with Iraqi or Kurdish units on the ground, to call in more precise airstrikes and advise them on tactics, Barno said.

In the past, Obama has been determined to keep limits on a Pentagon that often pushes to extend military operations. He now is invested personally in the Iraq conflict as he was not before. He may wind up confirming a lesson that Iraq already proved once: Starting a war is easy. Ending one is much harder.

Obama already has faced criticism from Republicans, some of whom urged him to use more firepower.

“Frankly the threat posed by [the Islamic State] requires a more fulsome response and a more comprehensive plan than has thus far been put forward by the administration,” House Majority Leader Kevin McCarthy (R-Bakersfield) said in a statement Friday. “We shouldn’t wait until terrorists are at the doorstep of U.S. personnel or are threatening thousands of civilians with death on a mountaintop to confront this threat.”

Such criticism could wear on Obama’s already sliding approval ratings, particularly on foreign policy. But White House aides were more concerned with reassuring Americans, particularly in the Democratic base, that the president was not embarking on another war in Iraq.

The White House offered repeated assurances Friday. White House spokesman Josh Earnest declared a “specific presidential commitment” to avoid a prolonged campaign.

But senior administration officials put no time frame on the bombing and offered no definition of success. In a conference call with reporters, they said U.S. warplanes could bomb around Baghdad or anywhere else in Iraq where American personnel and facilities are at risk from advancing militants.

About 5,000 Americans are stationed at the U.S. Embassy in Baghdad, including about 200 U.S. military personnel who guard the facility and work with Iraqi forces at a joint operations center. An additional 500 U.S. troops are at the airport, coordinating delivery of military assistance. “This is actually open wide to an expansion,” Barno said. “There should be some concern that there really aren’t any legitimate limits on what we might do.”

The risks of an open-ended air war were shown when Obama agreed to intervene in Libya in 2011. The U.S. joined what was initially called a limited international effort to halt attacks on civilians. The bombing campaign dragged on for months before rebels overthrew Libyan dictator Moamar Kadafi. The country is again torn by violence today.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.