Obama-GOP rift over Iran talks redefines partisan battles

- Share via

Reporting from Washington — President Obama’s hope of closing out his second term with legacy-shaping achievements on the world stage has invited the same bitter congressional opposition that has long thwarted his domestic agenda, producing a new power struggle that challenges the traditional limits of partisan battles in Washington.

The disclosure this week that Republican senators sent a letter to Iran about its nuclear program is the latest example of how Obama’s GOP critics have ignored the traditional deference to a commander in chief on foreign policy, while also reframing an issue of bipartisan concern in more starkly political terms.

The letter was released days after Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu warned at a rare joint meeting of Congress of the consequences of what he considered a “bad deal” with Iran.

Another point of contention is whether Congress should have a voice in approving any deal with Iran. Senate Republican leaders moved last week to start debate on bipartisan legislation subjecting any agreement to ratification by lawmakers, prompting Democrats to insist that the proposal be put on hold while talks proceed.

White House officials characterize the Republican strategy as reckless and partisan, designed to derail a foreign policy crafted by the Democratic president. They argue that the new level of attack on the president’s policy breaks with a decades-long practice of the U.S. speaking with one voice — the administration’s — on foreign policy.

“This letter sends a highly misleading signal to friend and foe alike that that our commander in chief cannot deliver on America’s commitments, a message that is as false as it is dangerous,” Vice President Joe Biden said in an unusual and lengthy statement, adding that he couldn’t recall senators writing to advise another country during his more than three decades in the Senate.

Republicans say their reaction is guided more by the president’s lack of respect for Congress’ constitutional prerogative to advise and consent in foreign affairs.

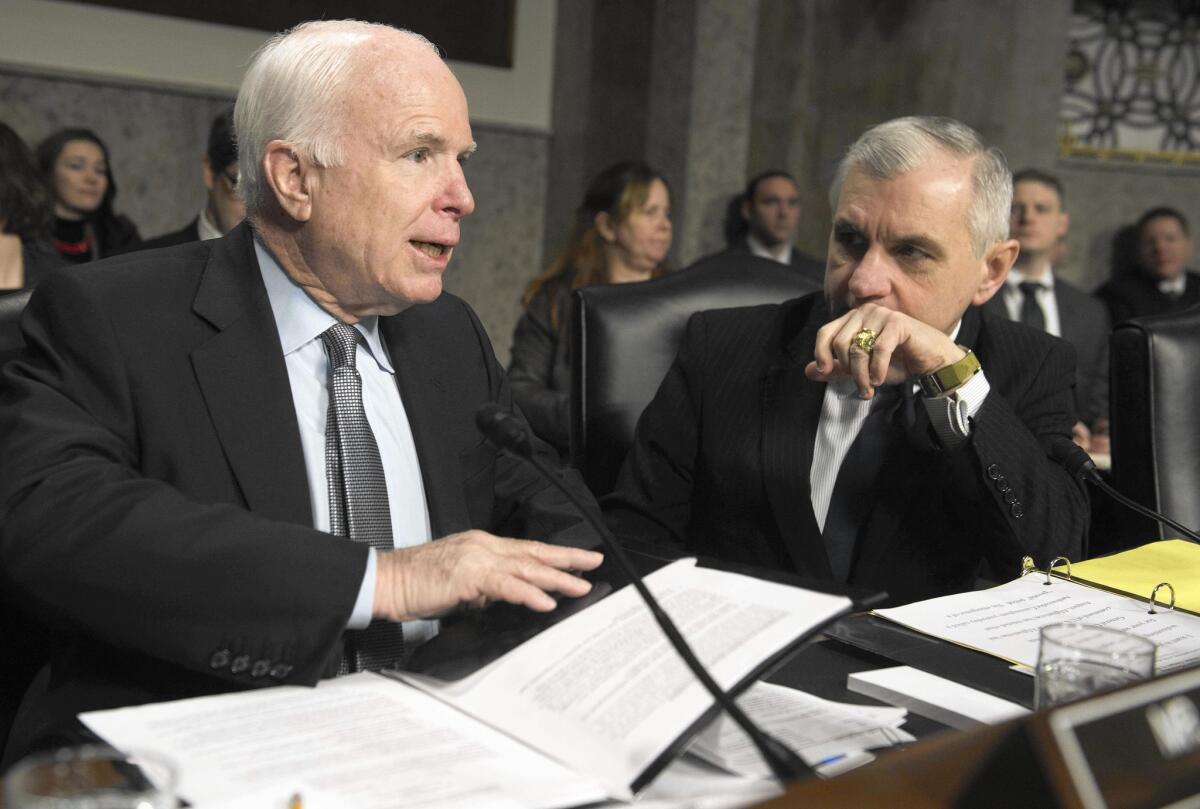

“I will take blame for maybe Republicans being pretty aggressive,” said Sen. John McCain (R-Ariz.). “But this president, unlike any other president I’ve ever known, is confrontational, noncommunicative, even to Democratic members of Congress. So you get a poisoned environment, almost the likes of which I’ve never seen.”

Party leaders view Obama, not Republicans, as controverting the post-World War II bipartisan tradition on foreign policy, one Republican aide said.

Public disputes between presidents and members of Congress over foreign policy are not new. Lawmakers have broadcast their contrary viewpoints repeatedly over the last century, on issues that include the formations of the League of Nations and the North Atlantic Treaty Organization alliance, and the Vietnam War and U.S. policy in Central America.

In 1987, Democratic House Speaker Jim Wright of Texas waded personally into peace talks involving Contra and Sandinista leaders in Nicaragua. In 2002, Democratic House members traveled to Iraq in an attempt to avert the American-led invasion.

And as President George W. Bush tried in 2007 to isolate Syrian President Bashar Assad, his administration sharply criticized Nancy Pelosi, the Democratic speaker of the House, for traveling to Damascus to meet with the embattled leader. The Bush administration said Syria failed to crack down on insurgents who used the country as a base for attacking Iraq and accused Assad of meddling in neighboring states.

Netanyahu was invited to speak last week by Republican House Speaker John A. Boehner of Ohio, a move that brought complaints from the Obama administration, which was not told of Boehner’s offer ahead of time, as is custom for a visit by an elected foreign leader. Netanyahu in effect took the position, unusual for a head of a foreign government, of leading the opposition to an American president’s agenda.

The dispute over Netanyahu represented a new height in congressional forays into U.S. foreign policy only in that lawmakers haven’t previously brought a foreign leader to challenge the president before Congress, said Anthony H. Cordesman, a national security analyst at the Center for Strategic and International Studies.

“You can use the word unprecedented,” said Cordesman, “but the question then is, ‘So what?’

“The effect isn’t particularly lasting,” he said. “He’s speaking as a politician more than as the voice of a nation, and that’s worth about as much as any floor speech.”

Talks between Iran and six world powers over its nuclear program face a June deadline, with the Obama administration aiming for a framework on a deal by the end of this month. Curbing Iran’s nuclear activities — a major U.S. security concern — has long been a goal of Obama’s.

Advisors to the president have skirted the question of how much of an effect the Republican-led strategy may have, but a White House spokesman suggested Tuesday that the U.S. is involved in a “complicated, sensitive negotiation” and that the letter from Republicans was “misguided.”

To be sure, Obama faces Democratic resistance as well. Sen. Robert Menendez (D-N.J.) cosponsored legislation that would seek to impose new sanctions on Iran in the event of a failed nuclear deal as well as the bill that could require congressional ratification of any agreement.

Democrats have said that if there is no progress by March 24 (a deadline somewhat at odds with the administration’s end-of-the-month goal to reach a framework agreement), they will renew their support for sanctions.

The White House has had to expend significant political capital to keep Democrats in line, the Republican aide noted, and may be nearing the limits of Obama’s ability to do so on Iran.

White House Press Secretary Josh Earnest said the president has always envisioned a role for Congress and consulted extensively with members on the negotiations. But “to essentially throw sand in the gears,” he added, was not “the role that our Founding Fathers envisioned for Congress to play when it comes to foreign policy.”

Inadvertently, the GOP’s willingness to cross boundaries has helped keep Democrats backing the president. On Tuesday, Senate Democrats echoed party leaders’ comments harshly criticizing Republicans’ recent actions.

“All these events of the last few weeks suggest the possibility, a sad possibility, of a Senate that will elevate partisan political division over careful and constructive deliberation even on the most critical security issues that affect the security of our country and the world,” Sen. Tim Kaine (D-Va.) said on the Senate floor.

The aggressive Republican moves on foreign policy have, however, provided a convenient rallying point for party leaders as their new congressional majorities have repeatedly stumbled in attempts to advance a domestic agenda.

The next question before them is when — and whether — lawmakers should vote to approve a deal with Iran.

Senate Foreign Relations Committee Chairman Bob Corker (R-Tenn.), who is sponsoring the legislation requiring congressional ratification of any Iran deal, is working to secure the 67 votes he would need to override a presidential veto. The bill would require Obama to submit any comprehensive agreement to Congress for a possible vote of approval or disapproval within 60 days. The president would be barred from waiving or suspending sanctions during that time.

“All of us should be suspicious of an administration that is so intent on keeping the elected representatives of the American people out of this deal,” Senate Majority Leader Mitch McConnell (R-Ky.) told reporters. “There’s only one conclusion you could reach, which is he intends to make a bad deal.”

Republicans also offered examples of areas in which Democrats showed little reluctance in challenging Bush’s foreign policy, particularly after winning majorities in both the House and Senate in his final two years.

It was after Democrats recaptured the House in 2007 that Boehner began his tenure as the top House Republican, and his immediate challenge was to sustain support among his increasingly wary colleagues for Bush’s foreign-policy approach.

“His first tough fights as Republican leader in the House were about Iraq funding, and basically fighting to make sure that Nancy Pelosi wasn’t able to end that war by defunding it,” Boehner spokesman Michael Steel said. “This has been an issue he has been heavily involved with.... And I think he’s genuinely frustrated by what he sees as missteps by the president.”

The Iraq war experience was formative for others too. After leaving a White House meeting with Bush officials in 2006 to discuss his recent trip to Iraq, one Democratic senator told reporters that he had made clear the areas on which he thought the administration needed to change course.

But “I shared with the president my hope that neither party uses national security issues as political clubs,” said the senator, Barack Obama of Illinois.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.