Leave it to Cory Doctorow to imagine a post-apocalyptic Utopia

Author Cory Doctorow tells us about a great book he has read this year and why he thinks dystopias are more popular in fiction than utopias. (Video by Gary Coronado / Los Angeles Times)

- Share via

What’s it like after our system collapses? After the climate spins out of control, the middle class diminishes to an infinitesimal speck, the very rich grab all the wealth and resources, traditional employment disappears, factories sit empty and hundreds of thousands opt out of society altogether? To Cory Doctorow, it’s not that far from where we are now, and not so bad after all.

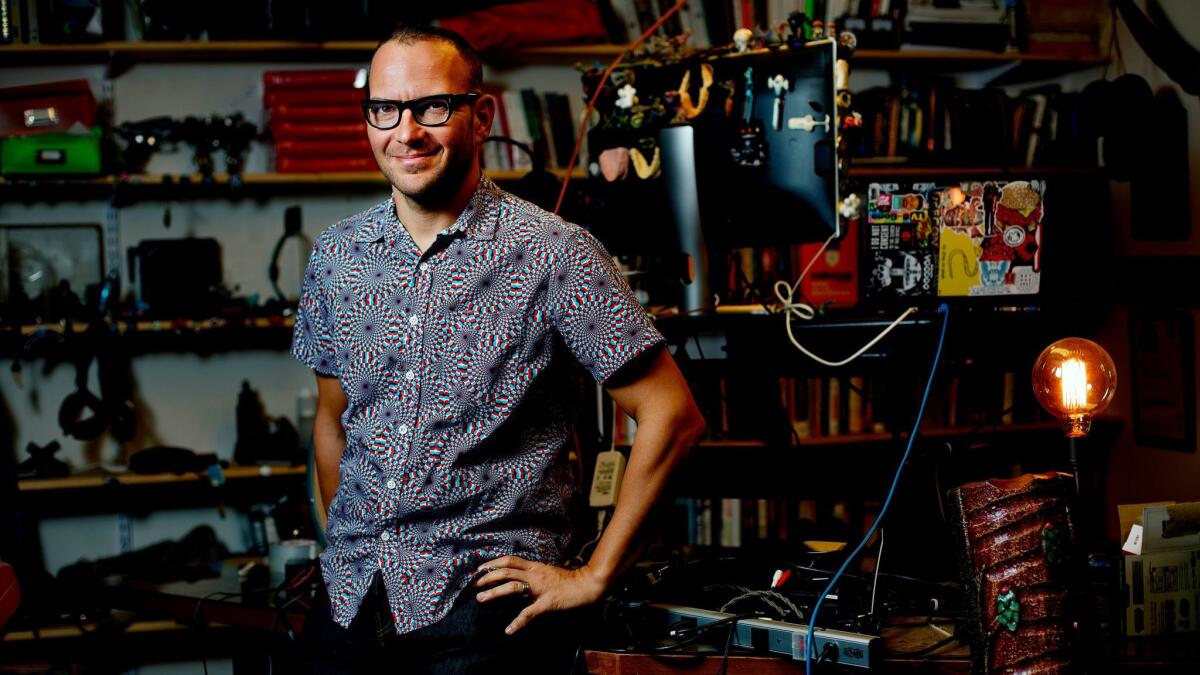

“I’ve hewed to what really happens in disasters,” says Doctorow of his latest book, the novel “Walkaway” (Tor, $26.99). Sitting in his Burbank backyard that includes a chrome-colored yurt, basketball hoop and surfboard converted into a coffee table, he continues, “This is one of the first disaster novels that says, ‘Disasters are the places where we put our differences aside to help each other but you still find things you can’t agree on.’ How do we dig out of the rubble?” Author Neal Stephenson and dissident Edward Snowden have offered their praise.

Doctorow, 45, is well aware of the line of novels — science fiction and otherwise — that see geologic or economic or political catastrophe as events to unleash our true nature as selfish thieves, furtive hoarders, zero-sum competitors, tribal antagonists, even hungry cannibals: George Orwell’s “1984,” the climate disasters of J.G. Ballard and post-apocalyptic chronicles of John Wyndham, Cormac McCarthy’s “The Road.” He admires all of these books.

But in the world of Doctorow’s “Walkaway” — named for a trio of young protagonists who join a burgeoning subculture of dropouts — people cooperate. They form walkaway communities in which noobies (the book is full of mid-21st century slang) are invited in to help create a new world. They forget about private property and have lots of sex. They use digital technology to make most what of what they need and disregard what they can’t.

Doctorow calls his post-apocalyptic world a Utopia.

Doctorow, a native of Toronto who, after numerous moves across the U.S. and United Kingdom retains the north-of-the-border soft “oo,” moved back to Southern California in 2015; he calls it “my third time living in L.A. and my fifth time living in California.” This arrival included a British-born wife who works at Disney Studios and a 9-year-old daughter whose middle name comes from the medieval Italian mathematician Fibonacci. He loves that Burbank still feels middle-class and has three year-round Halloween stores.

Besides his novels — which are in some ways second-wave cyberpunk — Doctorow is known as a kind of an anarchist pundit. One of the longtime co-editors of BoingBoing, he’s beloved by the Wired magazine crowd and the Electronic Frontier Foundation, for whom he once worked, for his arguments about the wonders of technology, the stranglehold of copyright, the virtues of maker/hacker/burner — a teched-up version of punk rock’s old DIY — culture, and the contradictions of contemporary society.

“It just seems like we’re in real trouble,” he says flatly, as he talks about the fight for real estate in big cities, the crushing dominance of finance, the replication of chain stores, the impersonal bureaucracy of corporate life and the fight for affordable college education. “It seems like a litmus test for an economic system should be whether it provides food, shelter and meaningful work for the people who live in it.”

And while he’s hard to map on a right-left axis — he’s skeptical of the marketplace, but not crazy about the state either — he falls squarely on the pro-technology side of the debate. “Technology is the answer to things like our inherent selfishness,” he says. “Trying to convince people that they should want fewer things has been a project for several thousand years and hasn’t worked out very well.”

Technological growth and networks — voluntary, clean, fast and effective — can do things both governments and capitalist markets can’t, he says. Creativity thrives that way, he says, through open-source software rather than digital locks. The collapse his novel describes is eased not by state action or the marketplace but by a walkaway network driven by the gift economy, a model anthropologists think dates to prehistory.

Conversations with Doctorow often work like this, circling from subject to subject, as he cuts an unpredictable path between familiar viewpoints and quotes

Our inability to really confront capitalism, says Doctorow — our thinking that the real problem is real estate policy or automation or some other factor — is a bit like the chain smoker diagnosed with

The characters in “Walkway,” for all their differences from Doctorow, are similarly fascinated with systems and ideas: Early in the novel, discussing the takeover of a tavern to which the walkaways have fled, one woman tells another that they are engaged in “the world’s most pointless Socratic dialogue.”

But it’s not all talk. The author sees his book as a pulp novel, driven by action. In Canada’s National Post, Tolkien scholar Tom Shippey call the book “a novel of ideas merged with a science fiction thriller, in which characters often speak in paragraphs before being interrupted by drone attacks and fight scenes.”

Doctorow comes to his interest in argument and ideas honestly, and the horrors of history were tangible to him early on: His father was born in an Azerbaijani refugee camp, and the author comes from Eastern European Jews on both sides. His folks were Marxist union organizers and at times he worked with his mother in support of abortion-rights activism. But despite his family's and his native Canada’s left-of-center stance, his grandparents were what he calls political reactionaries: Complex and theoretical discussions were part of most holidays and dinner times.

Novelist William Gibson, a longtime fan and friend, calls this mix of the abstract and the earthy Doctorow’s secret weapon. “Literary naturalism is the unrecognized secret ingredient in a lot of my favorite science fiction,” the “Neuromancer" author says by email. “The characters are sexual beings, socioeconomic beings, products of thoroughly imagined cultures, etc. Naturalism, which I suppose more people would call realism today, was very thin on the ground in much of 20th Century genre sf. If the characters have sufficiently convincing lives, that organically balances talkiness and theory, and Cory’s fiction amply demonstrates that he knows that.”

At times, Doctorow’s worldview and the day-after-tomorrow world he’s created in “Walkaway” seems a bit rosy, too trusting of human nature and digital innovation. But he’s no more a wide-eyed hippie than an

Timberg is a Los Angeles-based arts and culture writer. He's the author of “Culture Crash: The Killing of the Creative Class,” and tweets at @TheMisreadCity.

Sign up for our Book Club newsletter

Get the latest news, events and more from the Los Angeles Times Book Club, and help us get L.A. reading and talking.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.