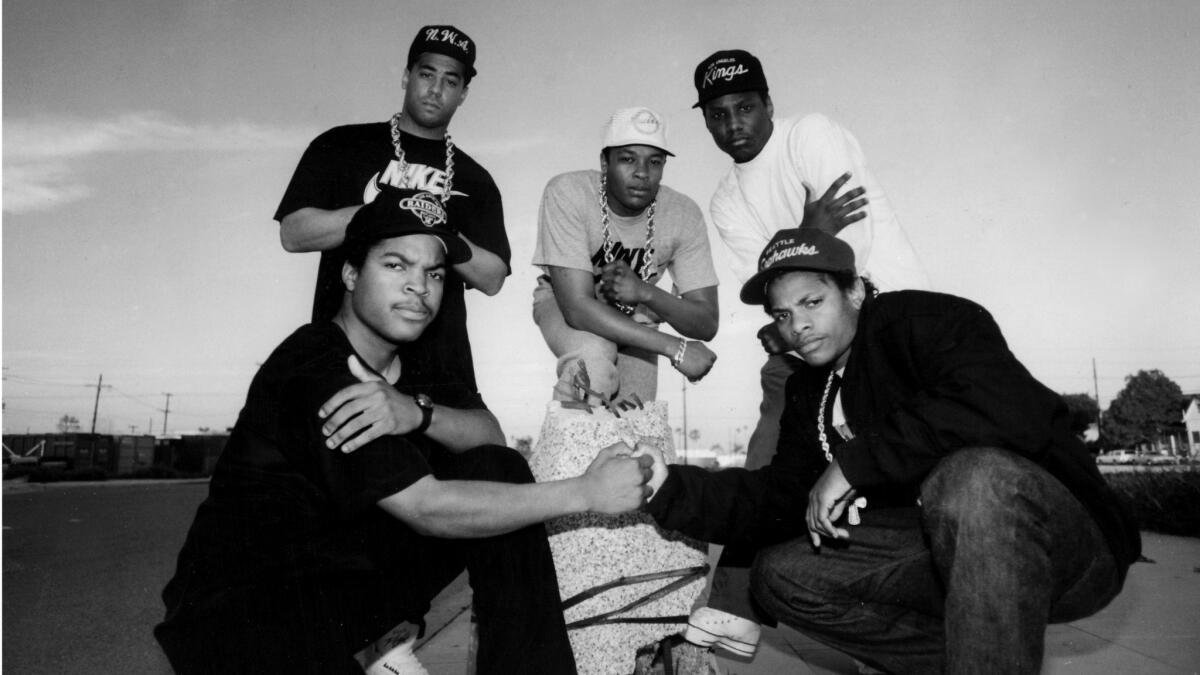

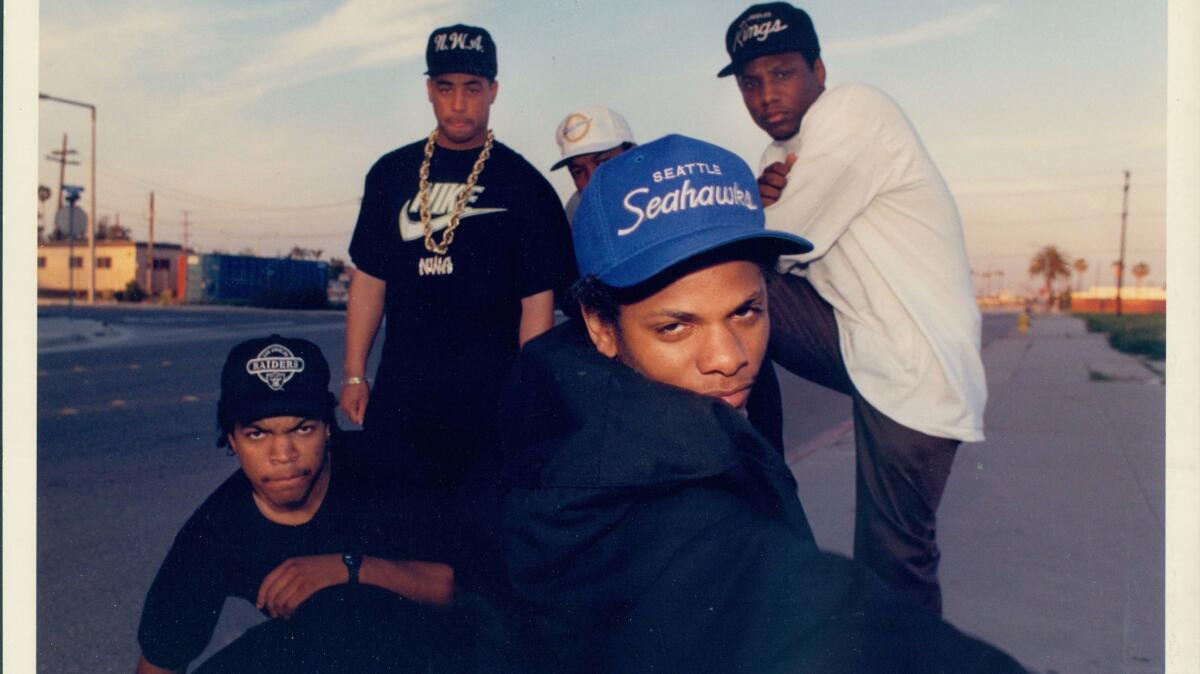

Chronicling the ascent and downfall of N.W.A — iconic, contradictory — in ‘Parental Discretion Is Advised’

- Share via

Flipping through Gerrick D. Kennedy’s reprisal of the late 20th century gangsta movement, I had a loud guffaw when brotha quips, “the N.W.A were to hip-hop what the Sex Pistols were to rock.” The hip-hop to punk analog is well rehearsed because, as the story goes, they come from a similar place of disillusionment and frustration with the way things be. But the L.A. Times writer is more correct than he might’ve accounted for in that the popularity and cultural impact for both groups was largely predicated on aesthetics. By this, I mean both their styles — from appearances to linguistics — and the way they fashioned their shocking (for the time) political content could be contradicted by the behind-the-scenes happenings.

Kennedy’s book caps off a 25th anniversary of the moment hip-hop’s political utility became fully realized in the wake of the L.A. riots. Within a problematic mix of Afrocentricity and brutality, of testosterone and lawlessness, black men were awakened by one another’s struggles to live in peace under the hand of the LAPD. The story of Ruthless Records is the story of Compton in a blazing rage; it’s the story of black independent business undone, internally, by the very forces it sought to fight off: betrayal, backbiting and a trickle-down business practice that saw adroit hip-hop lifers like D.O.C. and Ice Cube receiving the short end of the stick — at least early on.

The main draw for an otherwise “violent, misogynist, and problematic” group like N.W.A was its “vital response to the growing disenfranchisement from the Reagan-era politics,” Kennedy writes. Although he doesn’t go long on lyrical analysis here, he does draw the lines connecting policy choices of the early ’70s — namely Nixon’s “all-out offensive” against drugs and the establishment of the DEA — to the makings of a mogul like Eazy E.

Eric “Eazy E” Wright is the lead star, whose story begins in 1985 when the crack epidemic — and the potential profits that could be made — drew the 21-year-old outside the comforts of his two-parent, middle-class household to start dealing. Eazy E was not just the godfather of gangsta rap, he was the one member of the N.W.A with eyes and ears closest to the streets.

Kennedy is a deft storyteller, ducking and diving through the origin stories of Dr. Dre, Ice Cube and their early meetings with label co-founder Jerry Heller. Weaving in and out of those innocuous, utterly irritating studio sessions wherein Dre coached Eazy into being a halfway-decent rapper, Kennedy is adept at setting the stage and all its players. And while there are a few time jumps, he runs through the history of Dre’s World Class Wreckin’ Cru up to Eazy E’s fight with AIDS and death in 1995.

Kennedy writes of N.W.A’s preeminence as if still in awe of its reach even today. Dre’s evolution from the “dancey techno” of the Wreckin’ Cru to the soul-inflected funk samples he’d base a billion-dollar business upon is told with a genuine excitement. There are no shortage of moments when Kennedy breaks down Dre’s infamous samples of James Brown or Parliament. Even more, he contextualizes the N.W.A’s popularity within the racist history of popular music mediums like MTV that were hesitant to give black people any airtime (until the King of Pop himself made it impossible not to). It really wasn’t until the N.W.A reached critical mass in the summer of 1989 that black folks had their own lane in popular media.

Contradictions abound in the story of the N.W.A, and although Kennedy does not name them as such, he does draw them out with ease. For a group that was so much against Reagan’s trickle-down economic plans, Jerry Heller and Eazy were really good at implementing them at Ruthless Records. With a heady combination of interview and fine-toothed combing through available research, Kennedy pieces together N.W.A’s downfall with an informed precision.

Ice Cube’s financial disagreements over light royalty checks and leaky contracts with Eazy are well noted. “The way Cube saw it,” Kennedy writes, “Jerry was taking them all for a ride — and coaxing Eazy into making decisions.” However, an interview with Tracy Jernagin suggests otherwise: “It wasn’t like Jerry was all the brains and Eazy was aloof or just a frontman of this label and all this stuff people think. … Jerry really did follow Eazy’s lead.”

The deal Heller made with D.O.C. — the Dallas-born artist behind some of the group’s hottest verses — is even more villainous. The behind-the-scenes genius of the crew sold off the rights to his work for a gold chain and a handshake. That’s just how they got down.

Another problematic contradiction was, of course, how Dre and Eazy abused the women in their personal and professional lives. N.W.A was male-centric, and misogyny within N.W.A’s lyrics was not a case of separating the art from the artist. Kennedy details Dre’s abuse of girlfriend Michel’le, who, “was so accustomed to the abuse, she said, that she grew weary whenever too much time passed between incidents.” The infamous 1991 altercation between Dee Barnes and Dre — when Dre slammed her into a brick wall at a nightclub — is quickly retold with the added detail of what other members thought of the violence. “Ren said Barnes ‘deserved it.’ Eazy bragged that the ‘bitch had it coming.’ ”

On the other side of this line, not only did Ruthless Records produce Michel’le’s hit record, “No More Lies,” but it signed female artists such as Tairrie B (who also claims to have been punched twice by Dre after she released “Ruthless Bitch”), and the all-woman gangsta group J.J. Fad. Yes, Ruthless was Afrocentric and paving ways for female artists at the time, but at the cost of those women’s bodies, their psychological well-being and the unfortunate fact that their destinies were tied up in men who did not care for them.

Interviews with the likes of DJ Greg Mack, rapper Cold 187um and master penman D.O.C. power the narrative, offering insights into the group’s competitive edge and eventually how everything fell apart. Cube’s contractual dispute predestined Dre’s thumbing through the numbers; eventually he left Ruthless as well. Following a few diss tracks on Cube’s legendary solo records “AmeriKKKa’s Most Wanted” and “Death Certificate” and N.W.A’s “Niggaz4Life,” Dre started Death Row Records with the volatile figure Suge Knight, leading to another epoch in gangsta rap’s history.

Love is a culture critic from Houston focusing on the ways racial and sexual politics impact multimedia storytelling.

“Parental Discretion Is Advised: The Rise of N.W.A and the Dawn of Gangsta Rap”

Gerrick D. Kennedy

Atria: 288 pp., $26

More to Read

Sign up for our Book Club newsletter

Get the latest news, events and more from the Los Angeles Times Book Club, and help us get L.A. reading and talking.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.