Review: ‘The Partnership’ looks anew at Brecht’s creative circle

- Share via

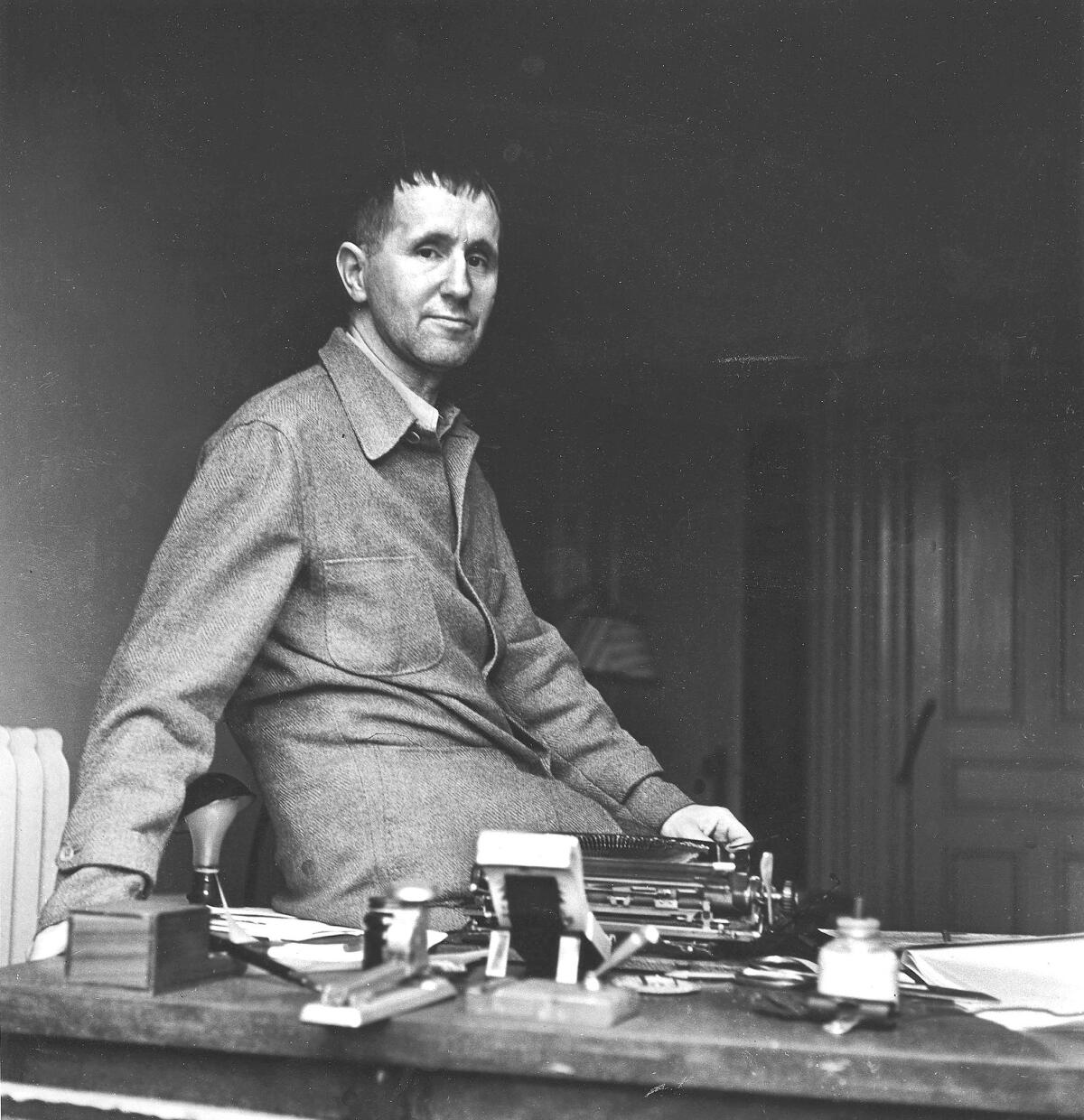

The German playwright and poet Bertolt Brecht (1898-1956) inspired extremes of loyalty and antipathy. Brilliant, charismatic and seductive, he was professionally unreliable and personally deceptive. He broke hearts at will and took credit for work not his own. The charisma arguably enabled all the rest.

Just how exploitative Brecht was, as a man and an artist, remains an unsettled question. John Fuegi’s controversial 1994 book “Brecht & Co.: Sex, Politics, and the Making of the Modern Drama” portrayed the playwright as cruel, misogynistic and hypocritical — even psychopathic. Fuegi attributed much of Brecht’s dramatic production to talented, infatuated and eventually disillusioned or discarded lovers.

In “The Partnership: Brecht, Weill, Three Women, and Germany on the Brink,” Pamela Katz, a screenwriter and novelist, adopts a less strident view — of both the authorship imbroglio and Brecht’s admittedly complicated love life. Her account is readable, engaging and fair-minded, perhaps to a fault. It is also occasionally romanticized and repetitive.

Katz focuses on the creative alliance between Brecht and the avant-garde composer Kurt Weill (1900-50), both looking to challenge established aesthetic forms and a society they found economically unjust and morally bankrupt. Their greatest legacy remains “The Threepenny Opera,” a 1928 musical play that both critiqued and enraptured Weimar Germany. The work owed a debt (how great is debatable) to Brecht collaborator Elisabeth Hauptmann, along with assorted poets and John Gay’s 18th century original, “The Beggar’s Opera.” Together, Brecht and Weill (and Hauptmann) also produced a song cycle and a full-scale opera about the corrupt, sinful town of Mahagonny, the satirical musical play “Happy End” and a ballet with songs titled “The Seven Deadly Sins.”

Plenty of women populate Katz’s narrative — these were sexually licentious times, and even the mostly loyal Weill strayed, taking up with the wife of his set designer. The eponymous three, however, are actress Lotte Lenya, Weill’s wife and the most celebrated interpreter of his songs; Brecht’s (second) wife, actress Helene Weigel, who managed the Berliner Ensemble, dedicated to Brecht’s plays, after his death; and Hauptmann, Brecht’s indispensable writing partner and intermittent lover.

Their stories unfold against the backdrop of Weimar Germany’s political and artistic turbulence and the threat posed by Hitler’s appointment as chancellor in 1933. With the Nazis in power, Weill, who was Jewish, and Brecht, a Marxist with a Jewish wife, fled Germany. (Hauptmann, also endangered by her politics, stayed behind long enough to salvage Brecht’s possessions.)

The book opens with the first encounter between Brecht and Weill, on March 24, 1927, in a Berlin restaurant. Weill, a radio reviewer, already had praised one of Brecht’s plays and was looking for works to set to music. At first, Katz suggests, “Their quick understanding was akin to the mutual admiration that arises between skilled athletes.” Later, she writes, “it was not only the magnetic pull of each other’s gifts, nor the ferocity of their mutual goals, pushing Brecht and Weill together; it was the opposition from the outside world.”

Brecht and Weill never became friends, Katz writes, but for a while they had an unmatched chemistry. It peaked, she says, on a French Mediterranean beach, Le Lavandou, where they hashed out the revolutionary innovations of “The Threepenny Opera.”

Fuegi suggested that Hauptmann actually wrote roughly 80% of “The Threepenny Opera.” But Katz argues that “the notion of ‘true authorship’ is far from simple,” given Hauptmann’s deeply symbiotic relationship with Brecht. While “Hauptmann’s intelligent presence behind the typewriter” was essential, she writes, “Brecht was undoubtedly in command of the creative process.”

Katz looks more kindly too on Brecht’s compulsive philandering and the lies it necessitated, seeing divided affections and weakness rather than cruelty.

By all accounts, Brecht was belligerent and bossy when mounting his plays, and the “Threepenny” rehearsals were famously contentious. The relationship between Weill and Brecht — the latter of whom managed to wangle the lion’s share of “Threepenny” royalties — only deteriorated from there.

The men ultimately had divergent artistic and political goals: Weill sought to make opera a popular art form, Katz says, while Brecht wanted his plays to precipitate political change. But, she notes, “However significant these differences were, they paled beside their personal dislike for each other.”

Trying to apportion blame equally, Katz writes that “no creative space was big enough for two such large egos.” But it is worth noting — as this book does — that Weill, after settling in America and breaking with Brecht, would enjoy successful collaborations with the most distinguished playwrights and lyricists on Broadway.

The strength of “The Partnership” resides in how vividly it re-creates not just these remarkable men but also the women who contributed so mightily to their reputations. Weigel’s dignity, Hauptmann’s disappointment and abiding loyalty, and Lenya’s wildness and talent are haunting — and they add a rich undercurrent of meaning to the book’s title.

Klein is a cultural reporter and critic in Philadelphia and a contributing editor at Columbia Journalism Review.

The Partnership

Brecht, Weill, Three Women, and Germany on the Brink

Pamela Katz

Nan A. Talese/Doubleday: 480 pp., $30

More to Read

Sign up for our Book Club newsletter

Get the latest news, events and more from the Los Angeles Times Book Club, and help us get L.A. reading and talking.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.