Column: Congress’ top climate change denier continues his attack on states probing Exxon Mobil

- Share via

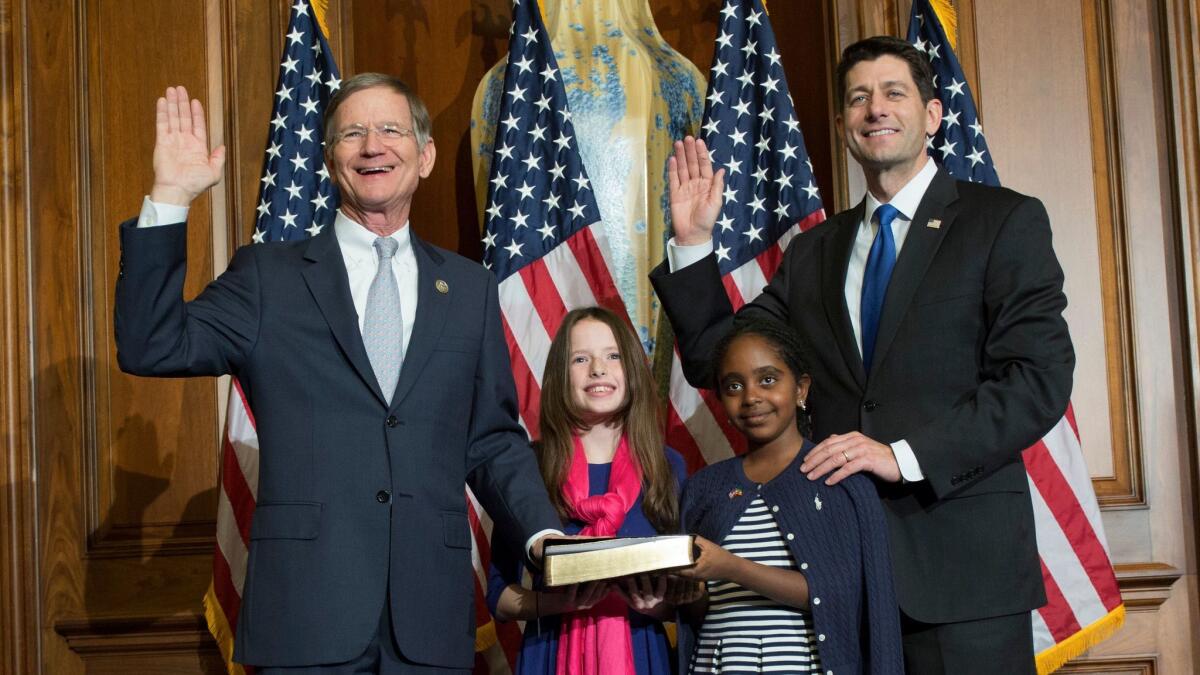

Rep. Lamar Smith (R-Texas) long has reigned as Congress’s preeminent climate change denier. From his perch as chairman of the House Committee on Science, Space and Technology, he’s harassed government officials, Earth scientists and other academics whose work refutes his position that the human role in climate change is a myth.

Lately, he’s moved on from trying to bully scientists by issuing subpoenas for their data and emails, to trying to bully state attorneys general investigating Exxon Mobil over allegations that it fraudulently undermined public understanding of climate change while possessing scientific evidence that the problem is real. The investigations stem in part from reporting by The Times and InsideClimate News into the company’s decades-long campaign, via misinformation and disinformation, to cast doubt on climate change science.

Two weeks ago, Smith subpoenaed Eric Schneiderman and Maura Healey, the attorneys general of New York and Massachusetts, respectively, for documents of their contacts with 25 climate activists, scientists and legal experts — among them former Vice President Al Gore and California billionaire Tom Steyer. The subpoenas were returnable on Thursday, but on that day Smith’s inbox was bare, except for messages from the attorneys general advising him, essentially, to stuff it.

The Subpoena oversteps the boundaries imposed by federalism, separation of powers, Committee jurisdiction, and pertinency requirements.

— New York Atty. Gen. Eric Schneiderman sends Rep. Lamar Smith packing

Smith didn’t need Schneiderman or Healey to tell him that his quest to defend Exxon Mobil from legitimate government investigations was more than quixotic, but idiotic: His committee received testimony to that effect back in September from the Congressional Research Service and from Charles Tiefer, a former legal advisor to the House and Senate. Tiefer told the committee that the House had never issued a subpoena “in two hundred years to a State Attorney General.” With good reason: The action signaled a potential breach of state sovereignty as enshrined in the Bill of Rights.

Here’s some background on Smith, whose credentials as a climate change denier are unassailable. He has dismissed a 2104 report by the United Nations’ Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change, which stated that “human interference with the climate system is occurring” and causes negative “impacts on natural and human systems on all continents and across the oceans” as “nothing new” and “more political than scientific.”

Responding to a White House report in May 2014 about the urgency of taking steps to address climate change, Smith said it was designed merely “to frighten Americans into believing that any abnormal weather we experience is the direct result of human CO2 emissions.” He added: “In reality, there is little science to support any connection between climate change and more frequent or extreme storms.”

In 2015, Smith presided over a move to slash NASA’s Earth science budget, a move disguised as a gift for space exploration. I described Smith’s announcement of the vote as “a model of misdirection and deceit.” It mentioned “space” and “space exploration” a couple of dozen times. Earth science got one mention, and that one was an undisguised political slam: “The Obama administration has consistently cut funding for ... human space exploration programs, while increasing funding for the Earth Science Division by more than 63 percent.”

Smith’s motivation for dismissing established climate change science and protecting fossil fuel companies such as Exxon Mobil isn’t hard to discern. If one adheres to the precept to “follow the money,” one discovers that pantsfuls of it flow from the oil and gas industry into Smith’s campaign accounts. Oil and gas contributors have directed nearly $700,000 in Smith’s direction since he entered in Congress in 1987; in the two congressional election cycles since 2013, when he became chairman of the science committee, oil and gas has been his top industrial source of campaign funding.

Smith’s efforts to protect Exxon Mobil from state investigators began in May, when he issued identical letters to 17 state attorneys general, including Schneiderman, Healey and California’s Kamala D. Harris (now a U.S. senator). The letter, signed by Smith and nine Republican colleagues on the committee, denounced the states’ cooperative “unprecedented effort against those who have questioned the causes, magnitude or best ways to address climate change.”

The letter said their “efforts to silence speech are based on political theater rather than legal or scientific arguments” on how to combat climate change. Smith demanded that they turn over within 12 days documents dating back to 2012 having to do with their contacts related to climate change with such organizations as the Union of Concerned Scientists and the Rockefeller Family Fund, as well as with the U.S. Department of Justice, the Environmental Protection Agency and the Obama White House. The attorneys general told him then to stuff it, too.

New York and Massachusetts are the only states to actually issue subpoenas thus far to Exxon Mobil, which may be what inspired Smith’s February subpoena. Schneiderman, in refusing to comply, delivered the back of his hand to Smith’s assertion that he had narrowed the scope of his demand to make things easier for the states. In fact, Schneiderman observed, the new subpoena is broader than the original demand — it targets not merely New York’s investigation of Exxon Mobil, but all communications with other attorneys general and the 25 named individuals. “The Subpoena oversteps the boundaries imposed by federalism, separation of powers, Committee jurisdiction, and pertinency requirements,” he wrote. Worse, Smith appears to be trying to do Exxon a big favor by demanding documents that the company itself has sought to obtain from Schneiderman in court, “so far to no avail.”

How long does Lamar Smith intend to embarrass himself, his committee and Congress in this ridiculous quest to shut down investigations that could harm his patrons in the petroleum industry? That’s hard to know, but what’s clear is that the interest he’s protecting in this quest isn’t the public interest, but Exxon Mobil’s.

Keep up to date with Michael Hiltzik. Follow @hiltzikm on Twitter, see his Facebook page, or email michael.hiltzik@latimes.com.

Return to Michael Hiltzik’s blog.