Column: Forget the squalling baby; Trump’s comments about China on Tuesday were the worse tantrum

- Share via

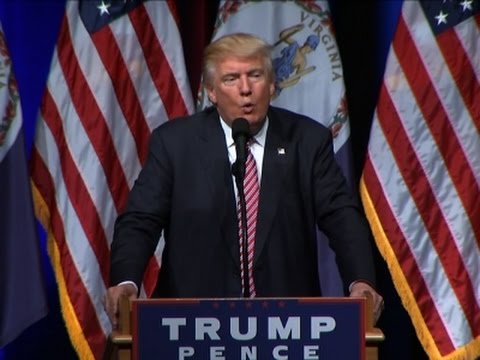

The big news takeaway from Donald Trump’s rally Tuesday in Ashburn, Va., was that he got irritated by a crying baby and ordered the tot and its mother out of the hall.

This was sadly typical of the tendency of the Trump campaign press — and let’s face it, the rest of us — to be distracted by the more childish elements of Trump’s behavior. But it’s a shame, because as a consequence nobody paid any attention to the policy discussion that Trump wrapped around his moments of preoccupation with the baby. That discussion dealt with China, and it was a good illustration of the Republican candidate’s once-over-lightly, soundbite-oriented approach to the real issues.

They have ripped us to shreds. Ripped us absolutely to shreds.

— Donald Trump on China

So let’s pick up Trump in the minute or so before he went on a tear about the baby. The exact topic was China’s devaluation of its currency, the yuan. We’ll start just after his initial notice of the baby, when he seemed to give approval to having the infant in the hall.

“When China devalues its currency (he said), they make it impossible for our companies to compete.… When China devalues its currency they take our guts out. And they do it so often, they do it so often. They’re constantly devaluing their currency and they always wait till like it’s a bad time like, we have a problem with Iraq, we have a problem with Afghanistan, every time we have like a big problem, they always devalue. And a year and a half ago they devalued, the biggest devaluation they’ve done in 20 years. The biggest in 20 years. And I said, man, how did they get away — but we had a problem, we were doing other things. OK. So when China does that, we have to fight back. Now here’s how you fight back. Because we can’t fight back any other way. We have the piggy bank. They have ripped us to shreds. Ripped us absolutely to shreds… — Actually, I was only kidding, you can get the baby out of here.”

And, scene.

Much of this is right out of Trump’s anti-China playbook. There are nuggets of truth and understanding sprinkled through, like fruit nuggets in a fruitcake. But the entire spiel adds up to unpalatable nonsense.

Yes, it’s true a devalued currency makes a country’s exports cheaper abroad and its imports more expensive, tending to reduce trade surpluses. Yes, China had a major devaluation recently — last August, not quite 18 months ago.

But the idea that China has in recent years been targeting the United States with devaluations, especially by waiting until the U.S. is embroiled in some crisis, is fantasy, currency experts say. So is the implication that the Chinese economy is controlled by a cadre of sinister masterminds who can manipulate it to their own domestic and international ends.

The truth is different and more mundane. China’s currency valuation reflects more than ever before the condition of its economy, and that’s not good. Devaluation is unwelcome to large sectors of the economy. Chinese policymakers, recognizing that devaluation is an issue of international politics, have been sensitive about accusations that they’re letting the yuan slide.

That showed up in January, when the yuan tumbled, setting off stock market losses around the globe. Chinese economic policymakers struggled to assure international trading partners that they were committed to supporting the currency’s price. As it happened, international markets were concerned both that they might not be telling the truth and that they weren’t actually capable of supporting the currency. (Chinese economic managers’ “attempts to bring troublesome stock markets to heel border on slapstick,” The Economist observed in January.)

More generally, the feeling in the market is that, if anything, the Chinese yuan is overvalued, rather than artificially cheap — that the weakness in the Chinese economy genuinely warrants a further devalued yuan.

Yet some economists say a devaluation would cost the Chinese economy more than it gains. Much of Chinese manufacturing’s parts and other inputs are themselves imported, so a devaluation raises costs for Chinese importers, potentially more than it cuts the prices of their goods abroad. Moreover, China has been trying to encourage consumption by domestic consumers, a goal that would be undermined by higher prices for goods from abroad.

See the most-read stories in Business this hour >>

Devaluation, furthermore, encourages capital flight out of China. The government already limits the sums that Chinese citizens can invest overseas, but current outflows aren’t close to the limit — devalue the currency, however, and the prospect is that the outflow in search of profitable investments elsewhere would become a torrent.

Put it all together, and the notion that China is in a position to manipulate its currency just to harass American manufacturers seems even more fanciful.

Trump didn’t go into his remedies for China’s supposed offense during the brief clip that emerged from his baby-hampered rally. But generally he has talked about imposing a tariff of 45% on Chinese imports “if they don’t behave.” (He also has proposed a 35% tariff on Mexican imports.)

Economists across the ideological spectrum have expressed horror at the trade war with China this would trigger. Peter Petri of Brandeis University has observed that low-wage manufacturing would shift from China to other countries, forcing the U.S. to extend its tariff wall globally. Rather than cut our trade deficit, tariffs retaliating against the U.S. goods would lead to a higher trade deficit, not a reduction. Petri estimated in March that the trade deficit of $736 billion in 2015 would grow by $67 billion. Other consequences would be reduced productivity and wages in U.S. industry, and possibly more than a million jobs.

Bashing China is a popular political sport, among Republicans and Democrats alike. But there’s a reflexive tone to it, like complaining about the DMV as a symbol of government bureaucracy. The China struggling to maintain growth today is “something less than a rapacious economic winner,” Jeffrey Rothfeder observed in the New Yorker in March. The value of its currency may be partially the result of centralized economic planning, but is responding more to market forces over which Beijing often seems powerless.

Any policies aimed at addressing imaginary foes and forces are doomed to fail. More frighteningly, they risk unleashing unanticipated consequences, and not good ones. And that’s if they make sense even in their own terms. Trump’s trade policies don’t.

“In order to qualify as a coherent set of policies, the policies have to not be cartoonish and the policies have to stand some chance of being actually enacted, Michael Strain, a resident scholar at the conservative American Enterprise Institute, told CNBC this spring. “I just don’t think Mr. Trump’s trade policies meet either of those criteria.”

That hasn’t stopped him. That squalling you heard at Tuesday’s rally wasn’t just a baby.

Keep up to date with Michael Hiltzik. Follow @hiltzikm on Twitter, see his Facebook page, or email michael.hiltzik@latimes.com.

Return to Michael Hiltzik’s blog.

MORE BUSINESS NEWS

Why U.S. tech companies can’t figure out China

Tesla-SolarCity merger embodies Elon Musk’s audacious plan for clean energy

Elon Musk tests Wall Street’s appetite for unprofitable cash-burning ventures

More to Read

Get the L.A. Times Politics newsletter

Deeply reported insights into legislation, politics and policy from Sacramento, Washington and beyond. In your inbox twice per week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.