Seattle’s grand experiment with the minimum wage

- Share via

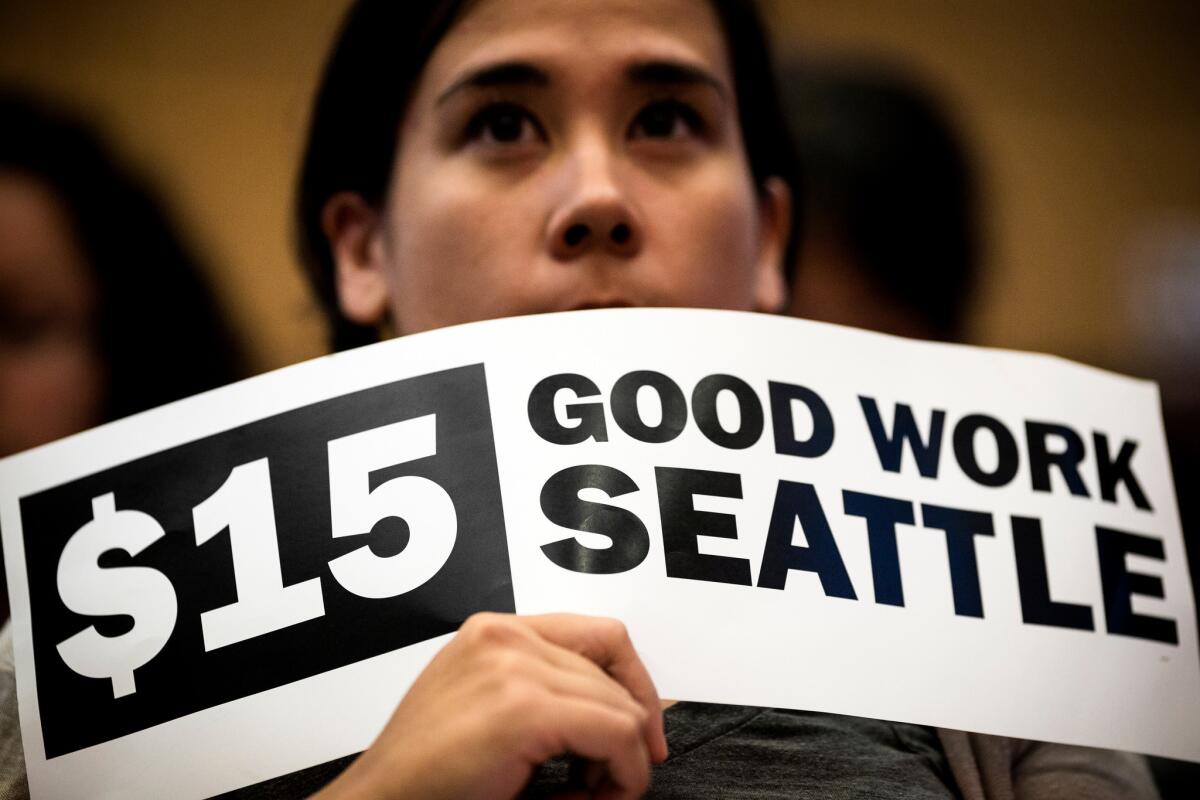

Seattle this week saw and raised skeptics on the minimum wage, as its City Council unanimously approved a $15 hourly minimum for the lowest-paid workers. The nation’s highest minimum wage will kick in over the next seven years, depending on the size of the employer and the benefits paid.

The rule places the city somewhat in uncharted territory. The $15 minimum is nearly 50% higher than the federal minimum of $10.10 an hour being pushed by President Obama and implemented by his executive order for new federal contracts — but it’s not as radical as some doubters claim.

For one thing, inflation will pare it down by the time it’s fully implemented in 2021 (though it will be indexed to inflation after that). For another, in a high-wage city like Seattle, $15 is not as far out of line as it might seem on first glance. As calculated by Arindrajit Dube, a minimum-wage expert at the University of Massachusetts, it’s about 59% of the median wage in the city.

That’s at “the high end by international and historical standards,” he has observed, but not by much. In 1968 the ratio in the U.S. for the federal minimum wage peaked at 55%, Dube told the Senate last year; today it’s about 37%. In New Zealand the ratio is 60%, and in France 62%. And in low-wage states such as Louisiana and Arkansas, the federal minimum wage has sometimes reached as high as 60% of the median.

Seattle’s minimum wage increase, which was the product of months of negotiations between business and labor interests with Democratic Mayor Ed Murray looking over their shoulders, will take place in stages. Smaller employers and those whose employees receive tips or health benefits will have longer to meet the standard. (See accompanying graphic.)

But the city’s hike to $15 certainly will challenge economists’ prevailing conclusions that increases in the minimum wage don’t lead significantly to job losses, or at least that the economic gains of the increase swamp whatever job losses do occur. As recently as February, the Congressional Budget Office concluded that an increase to $10.10 would reduce total employment by about 500,000 workers nationwide, but would also produce wage increases for 16.5-million workers, raise incomes for families living below the poverty line by a total of $5 billion, and move 900,000 people out of poverty altogether.

But that was for a wage increase much smaller than Seattle’s. Even Dube posits that an increase to $15 might lead to job losses as employers replace workers with machines. But he’s not sure.

The only place to go for empirical evidence thus far is Seattle’s small neighbor to the south, the airport community of SeaTac, which enacted a $15 minimum hourly wage as of Jan. 1 for hospitality and airport workers. There have been few reports of layoffs or cutbacks. At least one airport valet parking lot has imposed a 99-cents-per-day surcharge to cover what it says are its increased labor costs, but its owner told the Seattle Times that it didn’t have the option of cutting the workforce. “Whatever we do, service is key,” he said. “Anytime someone pulls into one of our lots, they’re greeted by a human being.”

That sounds like the way the process is supposed to work. More affluent customers — say, those who can afford to pay for valet parking at the airport — now share a bit more of their wealth with the low-income workers who tend their cars while they’re away.

Indeed, one good way to think about the increase in the minimum wage is as a small blow against rising economic inequality in the U.S., via the primary distribution of income. The methods, as listed by Jared Bernstein, a senior fellow at the Center on Budget and Policy Priorities and former chief economist for Vice President Joe Biden, “range from more union power to better balance that of capital, higher minimum wages, patent reform, restraints on the financial sector, charging polluters and financial bubble blowers for the negative externalities they generate, direct job creation to tighten the labor market and enforce a more equitable distribution of growth, and more.”

It’s proper to observe that all those ideas represent uphill battles, for the forces pushing incomes higher at the top end of the scale seem inexorable. The same day that Seattle enacted its $15 minimum wage, the Financial Times reported that chief executives at major banks around the world received average pay raises of 10% last year, for an average of $13 million each.

Did they deserve the money? As the FT pointed out, “the pay rises came in a year when banks paid record fines in the U.S. for wrongdoing ranging from mis-selling mortgages to violating U.S. sanctions.” The 15 banks surveyed paid $48 billion in fines last year, up from $30 billion in 2012. You can expect to see some of these people on CNBC, arguing that the workers at the lowliest end of the pay scale don’t deserve a raise.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.