Enron’s Skilling Avows Innocence

- Share via

HOUSTON — Former Enron Corp. Chief Executive Jeffrey K. Skilling declared himself “absolutely innocent” Monday and said he couldn’t imagine “in my wildest dreams” that the energy company would collapse into bankruptcy protection less than four months after his surprise resignation.

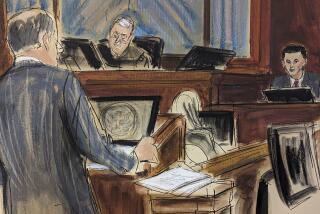

In a packed courtroom, with his wife, his ex-wife and his three children looking on from the front row, Skilling, 52, began his long-awaited testimony by saying he was proud of his role in propelling Enron to success.

“We were making the world better, in my opinion,” he said. “It was a fine company.”

Far from running away when disaster struck, Skilling said, he ignored legal advice to invoke his 5th Amendment right against self-incrimination and repeatedly testified under oath to Congress and regulators because he felt someone needed to combat the “witch hunt” that developed after Enron’s December 2001 implosion.

In the federal trial, which began Jan. 30, a parade of prosecution witnesses has testified that Skilling and co-defendant Kenneth L. Lay, 63, lied to the public about the company’s financial condition and participated in a scheme to hide losses and falsely pump up reported profit.

Their motive, according to prosecutors, was to keep Enron’s share price high and protect the huge fortunes they had amassed in Enron stock.

The two face decades in prison and millions of dollars in fines if convicted of the multiple counts of fraud and conspiracy facing them. Skilling also is accused of insider trading in Enron shares.

Besides being the dramatic high point of the trial to date, Skilling’s testimony is regarded by legal experts as his best chance to obtain an acquittal. Direct examination by his lead defense lawyer, Daniel M. Petrocelli of Los Angeles, is expected to last about two more days, followed by cross-examination by co-lead prosecutor Sean Berkowitz, who heads the Justice Department’s Enron Task Force.

Lay is expected to take the stand later this month.

Although he appeared calm and his voice was steady, Skilling said at the beginning of his testimony Monday morning that he was “probably a little nervous.”

“Why?” Petrocelli asked.

“In some ways my life is on the line,” he replied.

Skilling, dressed in a gray suit, white shirt and light-blue tie, spent much of his first hour on the stand explaining to the jury of eight women and four men why he abruptly resigned from one of the nation’s biggest corporations in August 2001, only six months after becoming CEO.

Skilling said that for more than a year before he quit, he was physically and emotionally exhausted by his job as president of Enron and increasingly conscious that its demands had kept him from devoting time and energy to his family and community.

“I concluded that the balance was totally out of whack, totally out of whack,” Skilling said, “and I had to change it.”

After a three-week vacation in Africa in the summer of 2000 with one of his sons and one of his brothers, Skilling said, he arrived back at work and told Lay, Enron’s founder: “I really hate this job.”

Lay persuaded Skilling to stay on and promoted him to CEO, but within months Skilling had again decided to leave.

“My head just wasn’t in it,” he said.

Besides, by the summer of 2001, Skilling said, he had become “a lightning rod” for critics of Enron, especially those angered by the company’s role in the California energy crisis of 2000 and 2001. Enron was accused of profiteering at the expense of consumers, but Skilling publicly blamed state officials for botching their energy deregulation plan.

At a speech in San Francisco in June 2001, a protester threw a cream pie in Skilling’s face, and hecklers denounced him as greedy.

Enron’s stock had fallen sharply in the first half of 2001. Short sellers -- traders who profit by betting that a company’s stock price will fall -- were attacking Enron and, in Skilling’s view, were behind negative stories that had begun to appear in the news media.

“In some ways, I had lost credibility with the Street,” Skilling said, referring to the Wall Street investment community.

Skilling said he felt it was a good time for a transition from the company’s perspective as well because he believed that Enron was in solid financial shape.

Asked whether he would have considered leaving if he had thought the company was headed for bankruptcy, Skilling said no.

“I will regret always that I left when I left,” he said. He added that the photos of laid-off Enron employees sitting on the sidewalk outside the company’s glass skyscraper after the bankruptcy filing made him “feel like I wanted to die.”

Skilling, subdued and undemonstrative when discussing the toll his job took on his personal life, became animated Monday when discussing the way he helped build Enron’s wildly successful merchant-energy business, beginning as a McKinsey & Co. consultant in the 1980s.

At Petrocelli’s invitation, Skilling left the witness stand and stood next to the jury box to conduct a five-minute seminar on his plan for transforming Enron into a profitable intermediary for natural gas producers and consumers. The plan was later adapted to the electricity market so that by the late 1990s, Enron -- far ahead of its competitors -- could deliver natural gas or electricity to customers anywhere in North America within hours of receiving an order, Skilling said.

Using maps and charts on a tall easel and gesturing with his hands, Skilling momentarily became the teacher he said he wanted to be when he resigned from Enron. In the month after his departure from the company, Skilling said, he lined up possible teaching stints at several business schools and -- for the first time in his life -- took his son to the first day of the new school year.

But in October 2001, when the Wall Street Journal started publishing articles critical of off-the-books partnerships headed by former Enron Chief Financial Officer Andrew S. Fastow, Skilling said, he became concerned that the negative publicity could shake the trust of Enron’s creditors.

He called Lay and Fastow and urged them to rebut the stories more aggressively, giving the media access to internal documents if necessary.

Skilling’s ideas were rejected, and he said he watched with increasing dismay as the company’s trading business -- which generated 90% of its revenue -- began to wither as trading partners withdrew credit.

When Skilling, on a weekend trip to Florida the next month, realized that the company would collapse, he began drinking wine, and “I went back to the hotel and I cried and I did not really recover for the rest of the weekend.”

Fastow became the government’s star witness after pleading guilty to conspiracy and agreeing to serve a 10-year prison term.

Fastow, on the witness stand last month, implicated Skilling in secret deals under which the Fastow partnerships were used to hide Enron losses and to fraudulently produce reported profits.

He quoted Skilling as saying, “Give me as much of that juice as you can,” a reference to the use of the partnerships to boost Enron’s reported profit.

Under Petrocelli’s questioning, Skilling denied Fastow’s allegations and those of other prosecution witnesses.

He said he had never considered bowing to the pressure and pleading guilty, as 16 other people have in connection with Enron’s collapse.

“It’s not in my nature to not fight something like this,” Skilling said. “I will fight those charges to the day I die.”

More to Read

Inside the business of entertainment

The Wide Shot brings you news, analysis and insights on everything from streaming wars to production — and what it all means for the future.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.