Review: Jacaranda gives an important concert featuring Peter Eotvos

- Share via

“Fierce Beauty,” the Jacaranda concert Saturday night at First Presbyterian Church in Santa Monica, was important. And it was important in several ways.

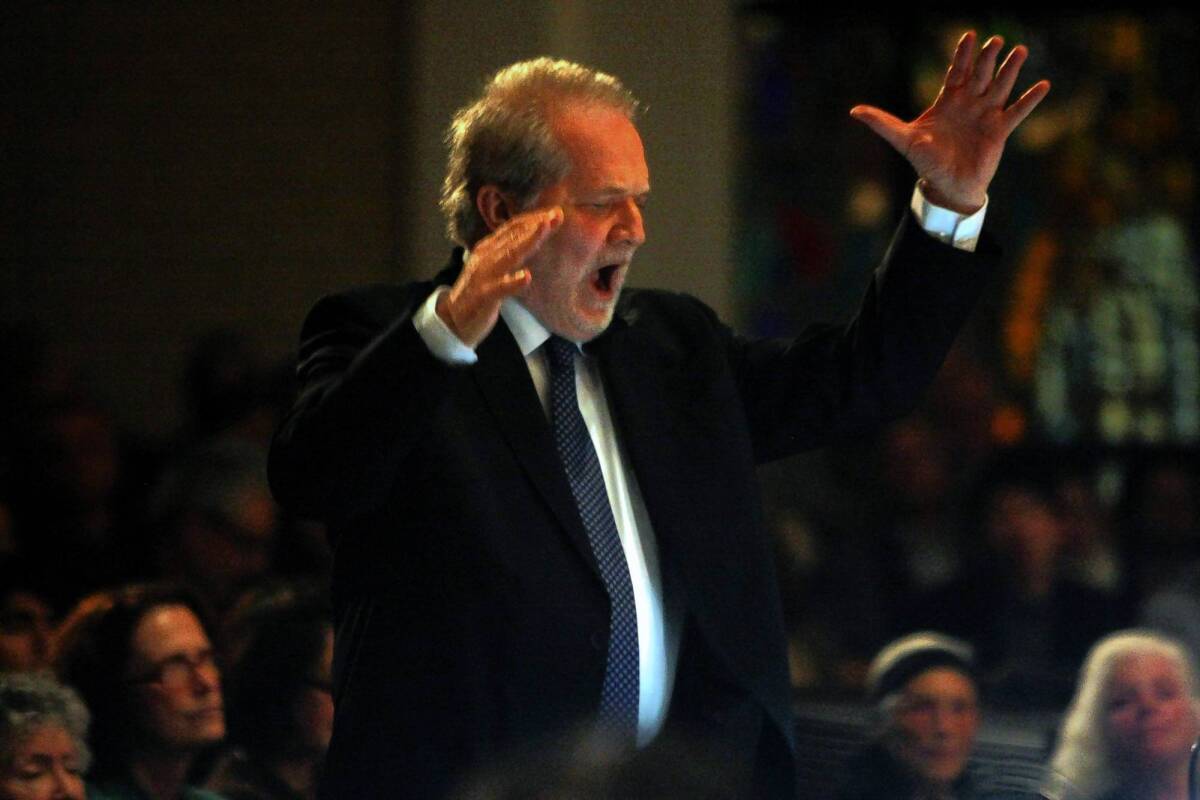

It began what will be a week of considerable attention on Hungarian composer and conductor Peter Eötvös. A major figure in Europe, he is too little recognized in the United States and his appearances here are infrequent. The Los Angeles Philharmonic’s upcoming “Focus on Eötvös” mini-festival is meant to help mend that neglect.

With demanding pieces by Eötvös and the famed late Hungarian composer György Ligeti, “Fierce Beauty” was the most ambitious undertaking so far and by far for Jacaranda. The performances were powerful, and Eötvös was on hand to conduct the U.S. premiere of a recent work, for which Jacaranda was a co-commissioner. With this concert, Jacaranda grew up, moving beyond local to national significance.

PHOTOS: Arts and culture in pictures by The Times

The evening was also an important model for collegiality among arts institutions, something startlingly rare in other places. The L.A. Phil not only provided the impetus for the program, but two of the orchestra’s patrons, David and Margaret Barry, stepped in to underwrite the co-commission.

Another reason to take notice was that a lot of people showed up, helping further cement L.A.’s reputation for attracting audiences to new music. Had a handful more tried to get into the 500-seat church, the fire marshals would have made a fuss. Eötvös received a hero’s welcome. There were not enough programs — or cookies at intermission — to go around.

But most important of all, the concert mattered because it was serious. It dealt with adult issues.

Eötvös’ “Korrespondenz” — a string quartet from 1992, which began the program — is a musical representation of a dialogue between Mozart and his father, Leopold, based on their correspondence. The composer has become a 22-year-old superstar in Paris; his pushy father is at home in Salzburg dispensing unwelcome advice. In the midst, Amadeus’ mother dies.

The Calder Quartet was seated with the viola and first violin on the audience’s left, cello and second violin on the right. The pairs represented father and son, with the quartet playing highly gestural music that is a musical setting of the letters’ texts. Those texts, however, are only printed in the score and not revealed to the audience.

What we heard, instead, was the tone of voice that the letters can’t convey. We got the body language. An Oedipal conflict was understood through revelatory musical psychology. The precise and to-the-point Calders, who have developed a relationship with Eötvös (they are working on a project for 2016 in Paris), brought it off brilliantly.

Eötvös’ new work, “Schiller: energische Schönheit,” is where the “Fierce Beauty” comes in. Written for eight singers, eight winds, percussion and amplified accordion, it also relies on 18th century letters, if more formal ones published by the German poet and philosopher Friedrich Schiller.

PHOTOS: Arts and culture in pictures by The Times

The texts are a startling examination of the moral and aesthetic role of the artist, of the function of beauty as insight or action in art, of the relationship in art between past and present, and finally of the relevance of the revolutions of clock time to revolutionary activity. The lessons are pertinent, and Eötvös makes them striking, whether by hitting a listener over the head with ferocity or by slyly turning terrible sounds into beautiful ones. He is an outstanding conductor, and the performance was riveting.

The context for the concert was that Eötvös is heir to Ligeti. The evening’s big Ligeti piece was his Piano Concerto in its chamber orchestra version, with Gloria Cheng as soloist and Scott Dunn, the associate conductor of the Hollywood Bowl Orchestra, on the podium.

One of the great late 20th century piano concertos, the five-movement work operates around intricate cross rhythms that often work at cross purposes, as does time in our seldom circadian lives. Movements tend to start relatively simply but head in the direction of controlled chaos. There is Ligetian weirdness at play with strange sounds and tunings, and an ocarina.

The solo part is nearly superhuman, and Cheng played it with a determined, tightly controlled fierce beauty. Dunn kept the work together, and that proved a proud accomplishment. But the church’s small stage meant the piano had to be placed in the rear, significantly reducing its dominance.

There were also youthful Ligeti works from the early ‘50s to give a little sense where such meaty and profound Hungarian musical goulash maybe came from. Six Bagatelles for winds were played with fine spirit by the Jacaranda Winds, and the Calder’s cellist, Eric Byers, gave an ideally eloquent reading of the intense, Bartókian Sonata for Solo Cello, showing that the fierce beauty is a quality of many shades.

MORE

INTERACTIVE: Christopher Hawthorne’s On the Boulevards

VOTE: What’s the best version of ‘O Holy Night’?

PHOTOS: Arts and culture in pictures

More to Read

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.