The tricky business of a Santa Monica street performer

- Share via

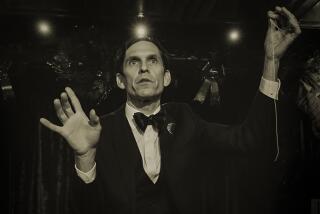

Bill Okal’s opening line is one of the oldest tricks in the close-up magic book: undersell your talent, then dazzle them with your best cards.

“I really only do two tricks,” the Bakersfield resident says apologetically to the two families standing in front of him on the Santa Monica Pier on a recent Saturday morning. He taps on three brass demi-cups perched upside down on a weathered cabaret table with pom-pom trim. “One is with cups, which I’m sure you’ve seen before…. The other, if you’re ready for this, is the legendary egg trick of Max Malini!”

The 76-year-old magician cups his hand to his ear. “Folks, this is not television, I need a little more enthusiasm if we’re going to make this work,” he continues, flashing a Cheshire grin. On cue, everyone laughs and a dozen more passersby stop, enough for the show to go on.

INTERACTIVE: Tour Los Angeles’ boulevards

Traditional street shows can be a tough sell in today’s era of mystifying televised performances by high-profile illusionists and endurance artists such as David Blaine and Criss Angel. But for Okal, captivating unsuspecting passersby with ages-old tricks is a thrill that, for now at least, is worth the hassle. Most Thursdays or Fridays, Okal leaves his wife and grip glue behind (he repairs golf clubs in his spare time) to make the four-hour round-trip commute to Santa Monica.

His first trick of the morning, if he’s lucky: landing a lottery-driven performance spot.

“I love the whole process of street performing, the hard work of getting people to actually want to watch you,” he says after a performance, wiping sweat from beneath his bolo hat. “Problem is, it’s gotten really difficult recently to get a spot.”

The challenge is securing one of the city’s premier and tourist-flooded outdoor street stages (at the Pier, Third Street Promenade or Transit Mall). In Santa Monica, the parks, beaches and other public areas are “open” performance spots. Los Angeles has a similar policy; street performing is legal without a permit, though restrictions like sound limits and whether performers can ask for donations vary widely.

The Pier also operated on a first-come, first-serve basis until 2010, when the city set up a lottery system to address the physical confrontations that often broke out between performers, says Aurora Piña, pier operations manager.

RELATED: In Hollywood, tourists see the good, the bad and the seedy

A snake charmer who goes simply by Pharaoh puts it more bluntly. “It got rough sometimes, some pretty bad fights,” he says, chatting with Okal after a recent lottery, snake-filled suitcase in tow.

Though Okal once landed a performance venue regularly, he considers a “good weekend” booking two morning spots. Each of the pier’s 24 designated venues is divided into three-hour performance increments , but eight of those spots are unavailable while the Pier undergoes a 12-month renovation. Okal doesn’t try for the afternoon slots because of the heat.

According to Piña, as many as 50 street artists (musicians, jugglers, cartoonists and the like) compete for those limited spots on summer weekends. Some prefer to camp out in the park on Ocean Drive rather than deal with the lottery, but Okal still holds out for the possibility of a captive ocean-front audience, even if that means performing only once over the weekend. “People don’t pay attention, there’s too much going on,” he says of the Promenade and parks.

The Pier also sees more than 6.5 million visitors annually, pretty good odds that some passerby might not have seen one of the oldest-known illusions.

Cups and balls

“This trick is so old, there is a painting of it on a wall in Egypt,” he says, pausing for effect halfway through the show. He rotates three brass demi-cups filled with tiny balls around his table. (Whether the Egyptian mural depicts the “cups and balls” trick or a different game is debated among scholars; the trick dates at least to Roman times, when stones and vinegar cups were used.)

Okal lifts the cups and almost everyone in the crowd, now more than three-dozen viewers strong, gasps; the tiny balls have been replaced by baseballs. “You’re not going to believe this, but a lot of times I do that, folks actually also applaud,” he jokes, clearly enjoying himself with the show in full swing.

Okal, a self-described “shy kid” from Springville, N.Y., wasn’t always so comfortable onstage. He met his first group of conjurers in the late 1950s when he hit the wrong elevator button to his community college dorm room floor and “suddenly the door opens to all of these magicians doing tricks.” He stayed all night.

PHOTOS: Arts and culture in pictures by The Times

In 1961 he put the card tricks on hold and enlisted in the U.S. Army Band Program. An Army pal told him about a magician named Eddie Fechter who owned several bar venues in the Buffalo area. “I spent so much time at Eddie’s bars, he finally told me I had to either do something or go away,” jokes Okal.

After performing the two tricks he had mastered, making a coin appear to vanish and bottom-dealing cards, he got his first late-night gig. “I guess he liked it, because after that, he’d tell everyone: ‘Here comes Bill Okal, the great bottom dealer.”

Sleight-of-hand illusions such as “bottom dealing” (appearing to deal from the top of a deck while pulling cards from the bottom) are known in the industry as close-up magic. It’s an evolving if not exactly dying art.

After that first bottom deal, Okal spent the next decade working in a law office by day and making the close-up magic rounds at night. Fechter eventually named one of his performance rooms after Okal; the two, along with magician “Obie” O’Brien, founded a convention dedicated solely to close-up magic called the 4Fs (Fechter’s Finger Flicking Frolic). Still, the magic remained in the hobbyist realm.

“It wasn’t until I moved to California that I really discovered what street performing was all about,” he says. He began performing on the San Francisco Fisherman’s Wharf and Ghirardelli Square before eventually landing a coveted spot on Pier 39. Each venue was privately owned, so performers were chosen based on skill — a luxury, he would later learn.

PHOTOS: Best in theater for 2012

Performing in Buffalo-area bars “back when everyone was doing shots all night” had its own audience attention span challenges. But the California streets were different. “The hardest part is getting the first ones to stop,” Okal says of his wary, wandering audience.

Throughout the 1990s the “congenial conjurer,” as Okal describes himself on business cards, supplemented his wavering street show income by performing private shows, among them a lucrative multi-year gig for corporate clients in Japan. After moving to Bakersfield with his current wife, he paid the bills with a variety of odd jobs, including a stint selling cookware in outdoor malls and other impromptu venues.

“I guess I was good at selling salad spinners because it was a live show, really,” he says, shrugging.

He gave the Santa Monica Pier a try for the first time three years ago while house-sitting for friend and local magician Alan Hayden. “You always have to figure out a new performance space, how to make it work,” says Okal, who still stays at Hayden’s home most weekends (the two occasionally perform together at the members-only Magic Castle in Hollywood).

Nearing the end of his show, Okal jokes that he needs “a big, burly man” as he pulls Savanna Sanchez, a petite 14-year-old from Sacramento, to the front of his makeshift stage. He uses the time to do “a few fun old tricks,” like making sponge balls appear and disappear around her head, and to remind the audience to stick around for his “legendary” egg trick — and the traditional passing of the donation hat.

“Folks, if you could pay after you went to the movies depending on whether you liked it, wouldn’t that be neat?” he asks, standing beside five eggs precariously perched on top of a plastic tray that is balanced on water-filled drinking glasses.

With his eggs at the ready, Okal puts on a blindfold then quickly pulls out the plastic tray. All five eggs land unscathed in the drinking glasses below. The audience cheers like they’ve just watched Houdini’s famous underwater shackle escape trick for the first time.

The showmanship works as well as the magic tricks. Okal’s hat fills with singles, fives, even the occasional 20. “I’ve gotten better at [the hat passing] part too,” he says, grinning after the show.

More to Read

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.