A drama critic’s turn to face the music

- Share via

Critics don’t get much respect. (Pause here for raucous laughter.) If you doubt it, look up the word “critic” in any book of quotations and see what you find.

H.L. Mencken’s “New Dictionary of Quotations” is full of zinger after zinger, most of which revolve around a single theme: Those who cannot do, review. I especially like this sulfurous couplet by John Dryden: “They who write ill, and they who ne’er durst write / Turn critics out of mere revenge and spite.”

Is that true? Not really -- yet there’s some truth in it, especially when it comes to my particular line of work. While a fair number of playwrights and directors have written criticism on the side, very few drama critics have changed directions in midcareer and written for the stage, and fewer still have had any luck at it.

I’m trying to beat those odds. On Saturday, the Santa Fe Opera will present the world premiere of “The Letter,” an opera by the Pulitzer Prize-winning composer Paul Moravec for which I wrote the libretto. It’s based on the 1927 play by W. Somerset Maugham, the British novelist who wrote “Of Human Bondage” and “The Razor’s Edge.”

You probably know “The Letter” from William Wyler’s 1940 film, in which Bette Davis played a pistol-packing adulteress. While the plot is mostly Maugham’s, our musical version is otherwise very different from the play. We’ve turned it into what Paul calls an “opera noir,” a fast-moving thriller that plays for 90 intermission-free minutes. (Imagine a cross between “Tosca” and “Double Indemnity” and you’ll get the idea.)

In case you’re wondering, I haven’t spent my whole life dreaming of writing an opera libretto. The thought of doing so never entered my mind until Paul invited me to collaborate with him. Nor am I a frustrated playwright: I love reviewing shows and writing biographies on the side. But now that I’ve got the bit between my teeth, I admit to being thrilled by the prospect of hearing my words sung on stage.

I also admit to having been both amused and touched by the words of an actress I know whom I ran into last summer in a theater lobby. She introduced me to her boyfriend as follows: “Terry isn’t just a writer and a critic -- he’s an artist too. He’s writing an opera!”

Yes, I laughed, but mainly because she blew the bull’s-eye out of the target. As far as I’m concerned, critics aren’t artists. In my capacity as a critic and biographer, I think of myself as an artisan -- a craftsman. One of the reasons why I believe this to be so is because I used to be an artist. I spent many years working as a professional musician, and that experience has conditioned my approach to criticism. I try to write not as a lofty figure from on high, smashing stone tablets over the heads of character actors and prima donnas, but as someone who has spent his whole adult life immersed in the world of art, both as a critic and, once upon a time, as a practitioner.

Fellow hyphenate

John Lahr, who writes about theater for the New Yorker, is another critic-practitioner, one with a short but impressive track record of success. He collaborated with Elaine Stritch on the book of “At Liberty,” Stritch’s autobiographical one-woman show, for which they shared a Tony Award in 2002 (and is now suing her for what he claims is his share of the profits).

More recently, Lahr raised a ruckus when he tartly pointed out that most of his colleagues on the aisles of Broadway “have no working experience of the theater, have not written a professional play, a sketch, or even a joke; have never worked in a theater, taken an acting class, or published any extended piece of work. They are creative virgins; everything they know about theater is book-learned and second-hand.”

Lahr then went on to claim that criticism is “a life without risk; the critic is risking his opinion, the maker is risking his life. It’s a humbling thought but important for the critic to keep it in mind -- a thought he can only know if he’s made something himself.”

That’s putting it a bit too strongly. Kenneth Tynan, the great British drama critic, wasn’t just kidding around when he quipped that a critic is “a man who knows the way but can’t drive the car.”

Many critics have managed to write well about the arts while keeping their creative maidenheads intact. But most of the best ones -- including Tynan himself -- have had at least some professional experience in at least one of the art forms about which they write. Harold Clurman, Edwin Denby, Otis Ferguson, Clement Greenberg, Randall Jarrell, Fairfield Porter, George Bernard Shaw, Virgil Thomson, Stark Young: These are the critics of the past whom I admire most, and except for Ferguson and Greenberg, each of them was also a practicing artist of high distinction.

New appreciation

I went to Chicago last month to review the premiere of “A Minister’s Wife,” a musical version of Shaw’s “Candida,” and I was struck by the fact that Austin Pendleton and Jan Tranen, who wrote the book and lyrics, had changed Shaw’s play in ways not unlike what I had done to “The Letter,” compressing it into a single 90-minute act and turning speeches and dialogue scenes into arias and ensembles. Because I had grappled with a similar set of theatrical problems, I was able to fully appreciate the dazzling skill with which Pendleton and Tranen sculpted “Candida” into a musical-comedy book.

Just as important, hands-on experience also gives critics a proper respect for what Wilfrid Sheed calls “the simple miracle of getting the curtain up every night.” It’s hard to sing Violetta in “La Traviata” or play the Stage Manager in “Our Town.” It’s scary to go out in front of a thousand people and put yourself on the line. Unless you know what it takes to do that night after night -- not just in theory but in your blood and bones -- your criticism is likely to be more idealistic than realistic.

What is true of the interpretive artist is truer still when it comes to creative artists. Those who paint or write poems, after all, are doing something that is fundamentally different from merely writing about other people’s paintings and poems. They’re making something out of nothing. As Stephen Sondheim put it in “Sunday in the Park With George,” “Look, I made a hat / Where there never was a hat!”

But what if no one likes your hat? Worse yet, what if some callous clod makes fun of it in print? Don’t get me wrong: It’s not a critic’s job to make a bad artist feel good about himself. But a critic lacking in empathy will find it hard to understand the creative process in anything other than a superficial way -- and the most effective way to acquire that empathy is to try making a hat of your own.

Needless to say, I didn’t agree to write an opera libretto in order to become a better critic, much less to impress the artists whose work I review. But I’ve found in recent months that a good many theater professionals appear to be pleasantly surprised that I’m putting my money where my mouth is. Together with Paul Moravec and the other wonderfully gifted men and women with whom I am collaborating on the premiere of “The Letter,” I’m submitting myself for approval -- not just from my fellow critics but from the people who read my reviews each week. On Saturday, they’ll find out whether I can walk the walk.

That’s why it means so much to me to be working on “The Letter.” I’ve become an artist again, and the sensation is both terrifying and exhilarating. I’ve never set foot inside a casino, but I can’t help but think that this must be what it feels like to place a big bet. Of course I hope I win, but even if I lose, I will be vastly richer in spirit -- and in empathy -- for having dared at last to roll the dice.

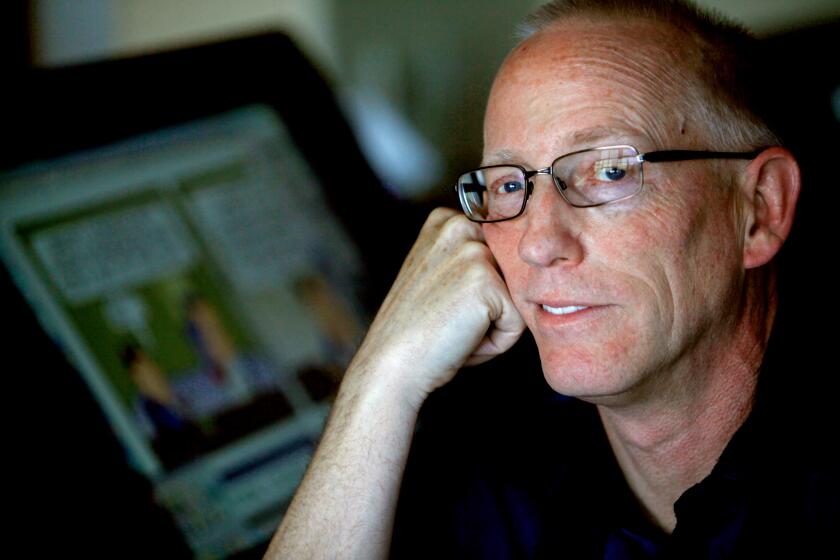

Teachout is the drama critic of the Wall Street Journal. His latest book, “Pops: A Life of Louis Armstrong,” will be published in December by Houghton Mifflin Harcourt. He blogs about the arts at www.terryteachout.com.

More to Read

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.