At satire’s forefront, cartoons press against hard lines

- Share via

It should come as no surprise that cartoonists would be a focus of attack by fundamentalist Muslim terrorists, like the barbaric assault carried out against the satirical Parisian newspaper Charlie Hebdo recently or, a decade earlier, the deadly violence that erupted in the wake of 12 satirical cartoons published in the Danish newspaper Jyllands-Posten.

Authoritarianism and cartooning are oil and water. Strict commitment to a set of irreducible beliefs and doctrines, which fundamentalists of every religious stripe maintain, is a big, fat, even irresistible target for a cartoonist — and it drives the object of ridicule crazy.

The late Christian fundamentalist pastor Jerry Falwell showed Americans as much in 1988 when he sued Larry Flynt’s smutty Hustler magazine for a salacious parody suggesting that Falwell had committed incest with his mother in an outhouse. While not exactly a cartoon, the satirical Hustler graphic was in the same ballpark as the often tasteless comics published by Charlie Hebdo and Jyllands-Posten — a crude but thorough demolition of self-righteous thought police. The U.S. Supreme Court ruled against the aggrieved pastor in a notably unanimous decision.

An expensive lawsuit is of course a very different weapon from the Kalashnikov rifles, Skorpion machine pistol, Molotov cocktails and hand grenade carried to Charlie Hebdo’s offices by an aggrieved pair of Muslim fundamentalists. They were seeking revenge, not justice — revenge for cartoon slurs against Islam. Acts of artistic vandalism were met with mass murder.

Yet cartoons are today the lingua franca of art — both high and low. A cartoon sensibility has long animated new painting and sculpture emanating from Los Angeles and London, Berlin and Beijing. And cartoons themselves rank as mass art’s most venerable form.

“Mass art addresses its audience from a madhouse, inmate to inmate,” wrote art critic Amy Goldin 40 years ago. Then, the cartoon sensibility at the core of 1960s Pop art was just beginning to break through into critical respectability after a decade of institutional resistance.

In her indispensable essay “The Esthetic Ghetto: Some Thoughts About Public Art,” Goldin was puzzling out art’s shifting relationship to different conceptions of a viewing public.

“The decorum of mass art is thoroughly irresponsible, fragmentary and nihilistic,” the critic continued, almost as if she were gazing into a crystal ball at Charlie Hebdo’s future Muhammad cartoons. “It’s a form-breaker, [being] almost too senseless to bear.”

The brittle, inelastic form that Charlie’s cartoonists so gleefully broke is double-edged.

As satire, whether brilliant and insightful at their best, or juvenile and xenophobic — and even racist — at their worst, Charlie’s cartoons are intentional slurs against a religious doctrine. They also violate a belief in some (though not all) Islamic traditions that any depiction of Muhammad is inherently blasphemous. Insult gets added to injury.

In one respect, the Paris tragedy represents a clash between two types of iconoclast. Those who oppose any veneration of religious images, which is at the root of the Muslim blasphemy claim, battle those who actively destroy that very concept, as Charlie’s cartoonists were happy to do.

Nowhere in the aftermath was this clearer than in the agitated drawing submitted the day after the massacre to Paris’ Libération newspaper by R. Crumb, America’s greatest underground cartoonist and a longtime resident of France. Crumb has given a good deal of thought to relationships between cartoons and religious texts, having drawn an extraordinary set of illustrations for the Christian Book of Genesis. (It was shown at the UCLA Hammer Museum in 2009.)

For Libération he began by making fun of himself.

Crumb inked a self-portrait trembling and sweating as the “Cowardly Cartoonist,” holding up a crude sketch labeled “The Hairy Ass of Mohamid.”

A speech balloon mutters that the sketch actually depicts the stubbly derriere of “my friend Mohamid Bakshi, a movie producer who lives in Los Angeles.” That’s likely a crack at Ralph Bakshi, whose 1972 animated version of Crumb’s iconic strip “Fritz the Cat” was not to the cartoonist’s liking — a desecration of something deeply personal, you might say, that nonetheless did not result in bloodshed.

The cheeky Libération cartoon adheres to fundamentalist Muslim restraints against drawing the prophet’s face. In the process, however, it also baldly ridicules the motive that terrorists claimed for murder. It scorns foolish claims — from all sides — about the pros and cons of iconoclasm.

There is nothing to debate. One good measure of civil society is knowing how to take appropriate offense. Images are to be engaged, not feared.

Form-breaking is one reason cartoons became so useful to artists in the last hundred years. Form-breaking was a mandate of art’s avant-garde.

Pablo Picasso, Cubism’s form-breaker extraordinaire, was crazy about the Katzenjammer Kids, an American comic strip that launched in 1897, created by German immigrant Rudolph Dirks. Rambunctious twins Hans and Fritz gleefully rebel against authority, personified by their bourgeois parents and their school’s truant officer. In the end, transgression inevitably gets them spanked.

A sleuth might be able to ferret out some subject affinities or stylistic similarities between the strip and the fragmented linear planes of radical Cubist art, especially still lifes of absinthe glasses, wine bottles, Marc brandy labels and cafe tables. “Hangover” is one translation of “Katzenjammer.”

But it’s more likely Picasso simply delighted in — and empathized with — the cartoon-kids’ worldview. He and Georges Braque were art’s Hans and Fritz, focused on dissenting from their artistic elders and becoming truants from the academy.

Marcel Duchamp wasn’t far behind. “Fountain,” his first readymade sculpture for public exhibition in 1917, was composed from a low-budget public bathroom urinal bought at a plumbing supply store and tipped on its back. He scrawled the signature “R. Mutt” across the front.

The artist explained that the name alludes in part to “Mutt and Jeff,” the first daily newspaper comic strip, created by Bud Fisher in 1907. A cue came from the cartoon’s working-class earthiness. Its title characters were a daft racetrack gambler and his pal, an inmate at an insane asylum. The artist, who took great pleasure in elevating meanings afforded by lowly puns, assumed the role of “our Mutt.”

“Fountain” was made for a show in New York organized by the Society of Independent Artists, which had bristled at the stodgy conservatism of the local art world. The society committed to showing every work of avant-garde art submitted to the exhibition.

“No Jury — No Prizes,” trumpeted their brochure. But Duchamp’s potty-mouth sculpture, which amounted to a vulgar cartoon, turned out to be beyond the pale. The society rejected it for display.

Cartoons inspired countless 20th century artists — Dadaists, Futurists, Surrealists, Fluxus publishers, Conceptualists, Neo-Expressionists, graffiti artists and more — who incorporated elements of them in their work. But Pop art was the major turning point. Cartoons now stood front and center, embodying high art.

They edged into the foreground in the late 1950s, nowhere more provocatively than in a prickly series of newspaper collages by Bay Area artist Jess Collins. Titled “Tricky Cad” — an anagram of Dick Tracy, Chester Gould’s square-jawed cartoon detective — they are sliced up and rearranged panels from the funny pages that undermine an authoritarian image during a socially repressive time. “Tricky Cad” pulls apart tidy police narratives, transforming them into darkly disordered nonsense poems.

Collins, a homosexual when being gay was not just stigmatized but a crime, had good reason to harness the disruptive, form-breaking power of cartoons. A similar motive soon propelled Andy Warhol, who elevated a subversive litany of gay-themed clichés to a position of cultural respectability and acclaim.

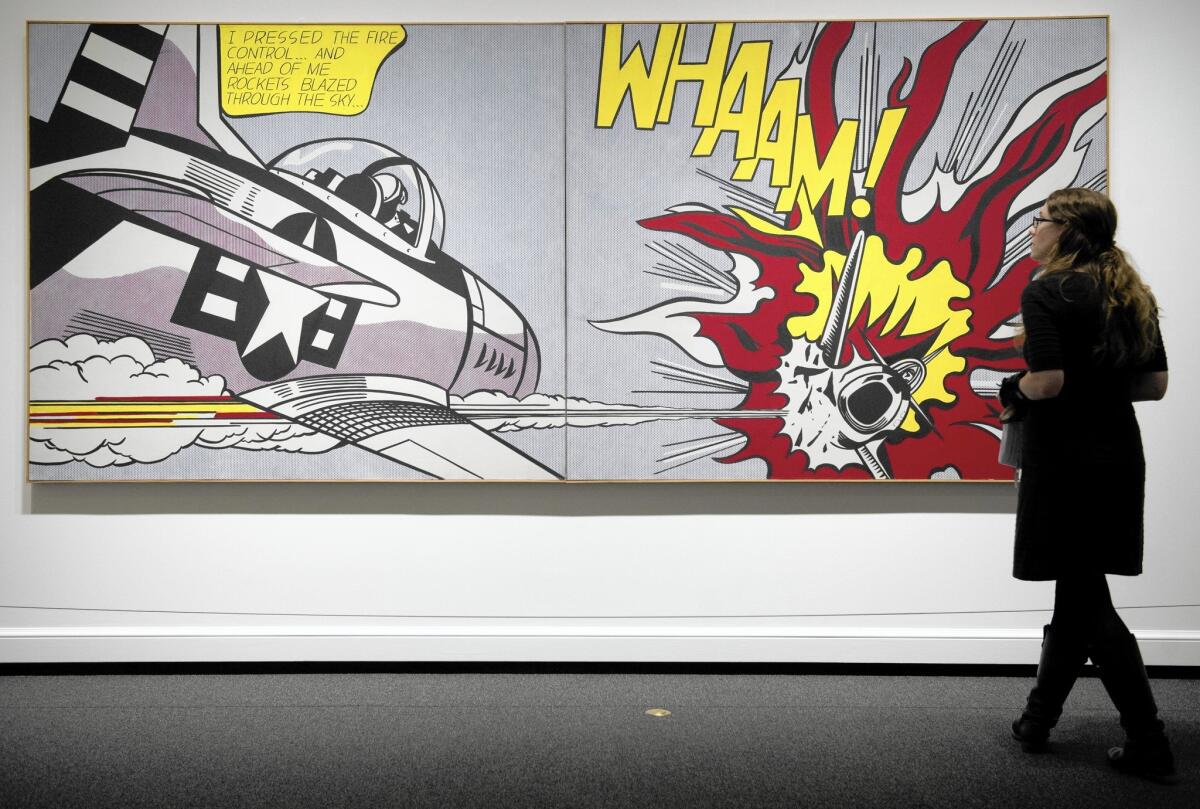

And Roy Lichtenstein, who pushed cartoons the furthest in his highly sophisticated Pop paintings, used them to undermine ideas firmly established in art culture. True Romance and World War II comics were primary sources for him, since all is fair in love and war.

In today’s still-immature digital age, when clipped and unfiltered utterances ricochet through Twitter, YouTube and Instagram to be delivered on smartphones and laptops, cartoon sensibility thrives. It feeds on rawness and lack of polish.

Which is not to say cartoons must thrive on witlessness, as gifted artists ever since Picasso and Duchamp make plain. The Charlie Hebdo massacre was witless in the extreme, fanaticism venting in the mass-art madhouse.

Charlie’s surviving editors and cartoonists surely considered that in their savvy decision last week to pump up the volume, printing 3 million copies in five languages of the first post-attack issue of their raucous newspaper. Prior circulation was just 40,000 and only in French.

Venting in the mass-art madhouse has its uses, some more trenchant — and appropriate — than others.

More to Read

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.