A storied art collection shrouded in mystery will anchor new UC Irvine museum

UC Irvine has been gifted the the storied Buck Collection for its planned Museum and Institute of California Art, or MICA. Here’s a rare look at the collection.

- Share via

When real estate developer Gerald Buck was selling a rural farm near San Luis Obispo, land he bought in a failed oil-drilling scheme, a prospective buyer offered him an elegant Old Master painting by Anthony van Dyck in lieu of cash. Buck had no interest in art, but neither did he have any other buyers in sight. So Buck plunged into researching the painting’s authenticity, history of ownership and market value — then agreed to the trade.

And he was off.

The Van Dyck is long gone, but now, four decades later, the Gerald E. Buck Collection has grown to more than 3,200 paintings, sculptures and works on paper. Not only is the vast trove the finest holding of its kind in private hands, the collection is poised to anchor an ambitious new museum being launched at UC Irvine.

Chancellor Howard Gillman is expected to announce Wednesday the formation of the UCI Museum and Institute for California Art, or MICA, with the Buck Collection as its core. The collection, much coveted by other museums, focuses on artists who emerged in California between World War II and 1980.

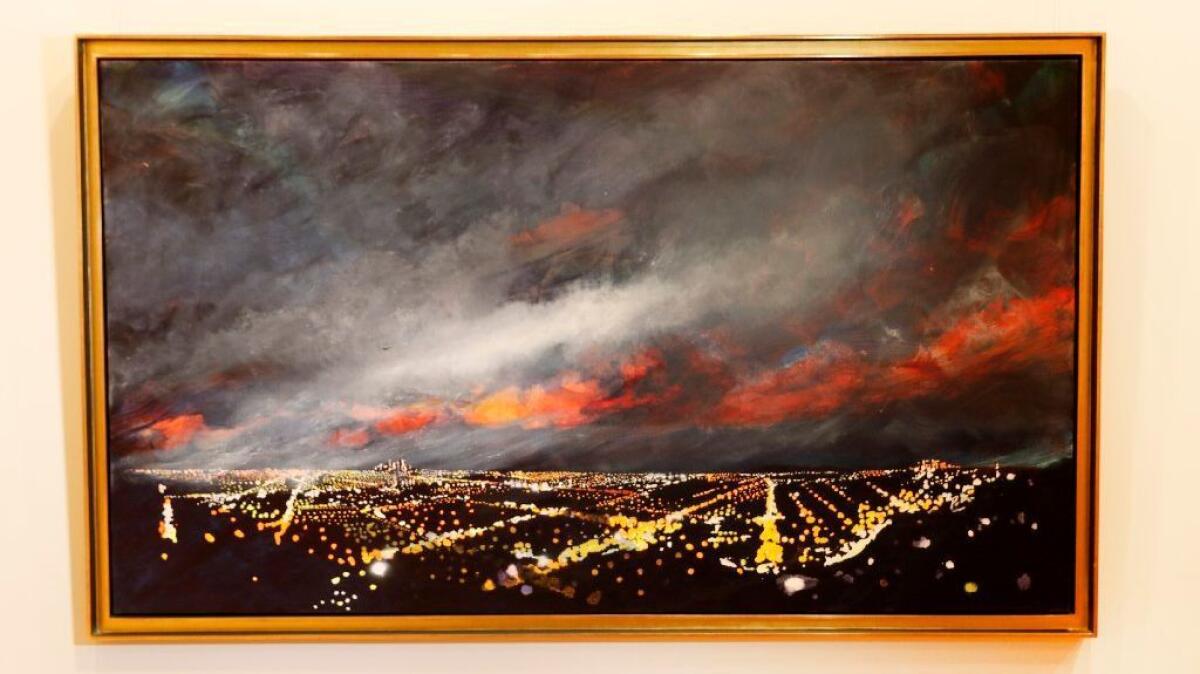

In addition to his art-filled home, where numerous major works were kept, a nondescript, unmarked former post office building a few blocks from the beach in Laguna provided a private place for Buck to study his collection. Few have ever been inside. When Stephen Barker, dean of UCI’s Claire Trevor School of the Arts, recently opened the building for The Times, about 80 works were on display in several large galleries plus offices, a small kitchen, a bathroom and hallways.

Storage racks held another 100 or so works. The remaining 3,000 items are at an art storage facility in Los Angeles. Many of the state’s most important artists are featured, including Joan Brown, Jay DeFeo, Richard Diebenkorn, David Hockney and Ed Ruscha. In all, they number more than 500.

When Buck began collecting seriously three decades ago, California was shedding its entrenched reputation as a regional, parochial art scene. Collectors like Edythe and

Some of the greatest collectors search below the radar, however, digging deep into under-recognized and undervalued territories. Buck is among them.

MICA has been a long time coming. When architect William Pereira unveiled the master plan for a new UC campus on a thousand acres of rolling rural farmland at Irvine Ranch in 1962, he identified a spot near the entrance as an ideal place to erect an art museum. Half a century after construction on the research university began, and after many uneventful years as a parking lot, the site will become MICA’s home.

News of the unrestricted Buck gift comes as a surprise.

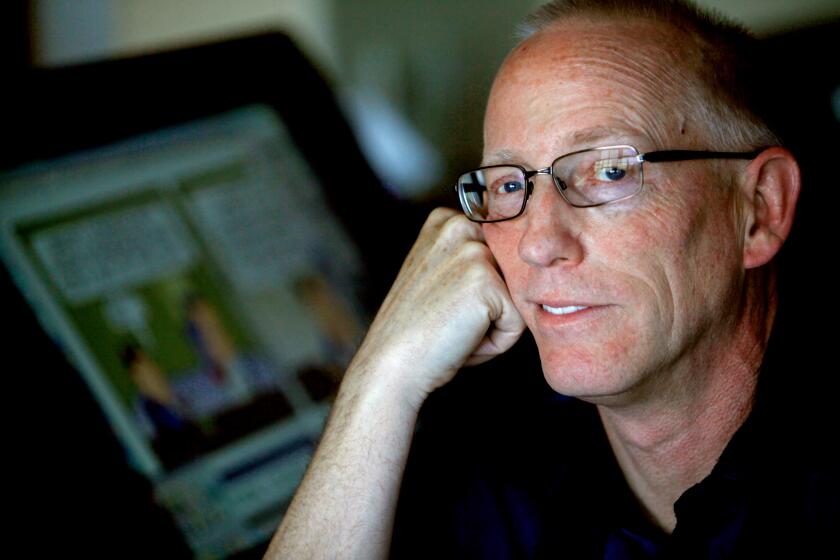

According to Barker, who will be executive director of MICA, it is unclear why Buck chose the school to receive the bequest. He was an exceedingly private person whose low-key presence made him an anomaly in Southern California’s high-profile art world, where flashier collectors hold sway.

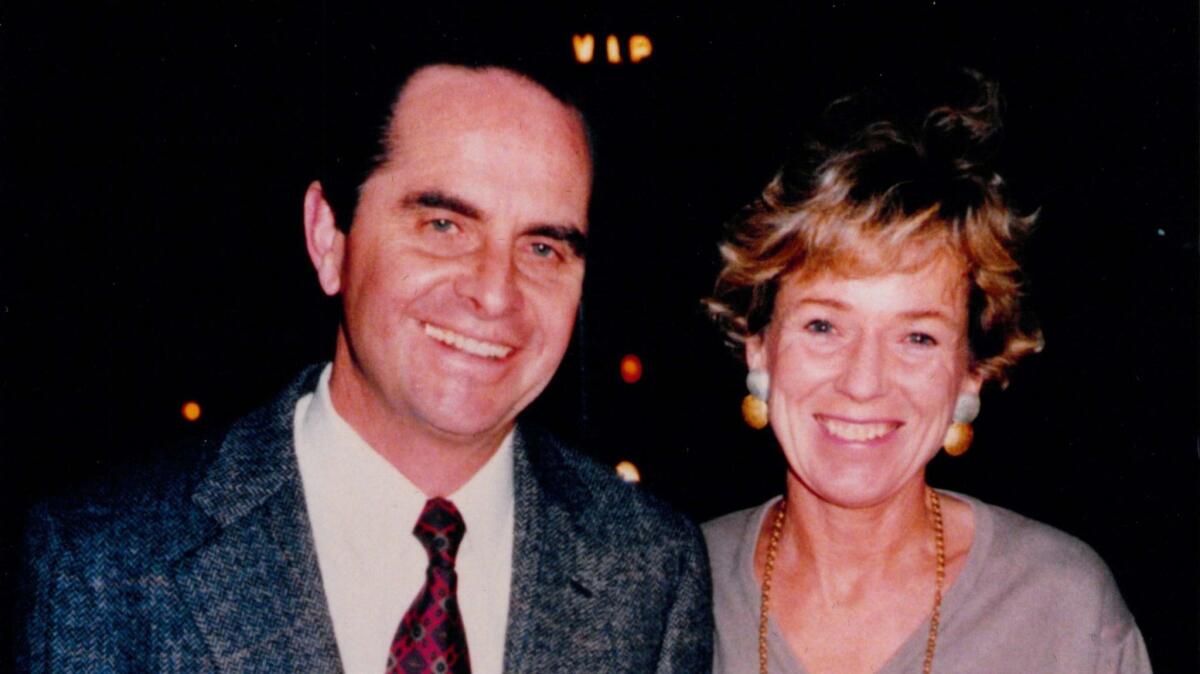

Buck, who died at 73 in 2013, lived in Newport Beach. Few knew the extent of his art collecting, and fewer still have seen the full fruits of his endeavors. A 2013 telephone call from a trust attorney notified the university of the bountiful legacy, which has taken years to work its way through probate. The collector, born in Culver City and an alumnus of UCLA, had no specific ties to the school.

“Perhaps,” Barker said, “it is simply because we are a prominent research university in the community where he lived.”

A research museum concentrating on 20th-century California art is distinctive – and potentially revelatory. The field remains woefully understudied.

Buck’s daughter Christina points to the possible influence of art historian Jonathan Fineberg, emeritus professor at the University of Illinois who befriended her father when he was a visiting lecturer at UCI.

Biological sciences form the school’s flagship discipline. UCI does have a small art gallery, as well as the Beall Center for Art and Technology, which promotes the intersection of the arts, sciences and engineering. A modest art history program resides in its humanities department, while the School of the Arts offers studio and curatorial studies programs. The plan for MICA is to develop a PhD in museum studies and a master’s degree in art conservation.

The Buck Collection includes scores of artists, among them Wallace Berman, Robert Irwin and John McLaughlin. It includes more than 10 works each by John Baldessari, Larry Bell, Bruce Conner and Llyn Foulkes. Six of the collection’s 10 Carlos Almaraz paintings, ranging from 1978 to 1989, are in the artist’s current retrospective exhibition at the

In addition to postwar art, the collection includes plein air, Social Realist and important early Modern paintings from the first half of the 20th century, especially in Southern California. Those holdings include metaphysical abstractionists Agnes Pelton and Henrietta Shore, Surrealists Knud Merrild and Lorser Feitelson, muralist Belle Baranceanu and colorist Oskar Fischinger.

The gift is accompanied by 398 file boxes of art books, auction catalogs, the collector’s notepads and acquisition records.

A research museum concentrating on 20th-century California art is distinctive — and potentially revelatory. The field remains woefully understudied. But the announcement coincides with a $2.5-million gift from the trust established by Buck and his late wife, Bente, to the Smithsonian’s Archives of American Art, where he served as a trustee; funds are targeted to its West Coast documentation program.

The collection’s 20th-century span made it an unsuitable bequest for a strictly contemporary art museum. Larger Southern California museums, such as LACMA and the Huntington Library, Art Collections and Botanical Gardens were considered but had been generally indifferent to many of the collection’s artists in the decades when the work was being made.

Smaller area institutions where Buck often lent art for exhibitions — Laguna Art Museum, Orange County Museum of Art and Palm Springs Art Museum among them — had expressed interest in the collection. For them, a gift would have been transformative, but their research capacities are limited.

Christina Buck said that after her father acquired the Van Dyck, he began to buy more European paintings, including an early Van Gogh. But soon he realized that forming a significant collection of such material was unlikely.

Buck switched to California Impressionism, an early 20th-century regional style based on a European model. His actual piece of the bucolic California landscape had metamorphosed into painted pictures of it.

Encouraged by veteran Los Angeles art dealer Tobey Moss, whose Beverly Boulevard gallery has specialized in art from the 1920s forward, Buck rapidly moved into more adventurous early Modernist and postwar California art.

“We got together at a crucial moment,” Moss explained in an interview. “He was a very confident person, very smart and aware of the forces of history.”

As the state’s pastoral landscape urbanized, partly a result of his own activities as an Orange County developer, so did the collector’s cosmopolitan taste.

Moss met Buck in 1984 when he came into her gallery and, intrigued by Helen Lundeberg’s dream-like Surrealist paintings and graceful geometric abstractions, began asking questions. Eventually Buck acquired 46 works from Moss, including seven of his 10 by Lundeberg spanning her career from the 1930s through the 1970s. (Paradoxically, he never lost the taste for elaborate, Van Dyck-era gilded framing, even for his most avant-garde pictures.) Other acquisitions included significant works by Feitelson, Merrild and Gordon Wagner.

Buck sold most of his traditional landscape acquisitions. A number went to Joan Irvine Smith, whose plein air collection formed the Irvine Museum in 1993. Ironically, those paintings too will find their way to MICA: The university announced last year that it had received the Irvine collection as a gift. More than 1,200 paintings by Guy Rose, William Wendt, Granville Redmond, Edgar Payne and other landscape and genre painters are included.

An appraisal of the Buck gift is underway, but a spokesman says the final tally will be in the “tens of millions.” For example, works of comparable quality to the 1952 painting “Albuquerque,” a large Abstract Expressionist masterpiece by Diebenkorn, have sold at auction for more than $6 million. Overall, the donation ranks among the largest gifts ever made to UCI.

The MICA project is not without hurdles. The target for completion is four to five years. The timetable is aggressive, and fundraising is required.

UCI’s Barker said that, given the prominence of the building site adjacent to the school’s Irvine Barclay Theatre, several leading international architects will be approached for a design competition as early as next summer. The budget is expected to be more than $100 million — and perhaps considerably more, when an endowment for operations is figured in.

The Buck Collection is unprecedented in scope but not comprehensive. Representation of the 1960s and ’70s Chicano, feminist and Black Arts movements, for example, is limited.

California is also unique in that its first major artist, Carleton Watkins (1829-1916), was neither a painter nor a sculptor but a photographer. In keeping with the state’s modern reputation for experiment and innovation, the camera was less than a generation old when Watkins began in the 1850s. Whether MICA will include camerawork, both still and video, remains to be seen; but collections of the stature of Buck’s can act as magnets for future museum philanthropy.

Southern California was on the brink of overtaking the Bay Area as the state’s artistic leader when Buck began his collection, and today L.A. is among the foremost global centers for new art production. Van Dyck notwithstanding, that would make the region’s new museum both essential and unique: MICA has the potential to tell the crucial story.

christopher.knight@latimes.com

ALSO

LACMA raises general admission price to $20

A masterpiece of Baroque painting, missing for more than a century, is hiding somewhere in L.A.

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.