Words and Pictures: In ‘Salon des Refuses’ mixed-media artist Lezley Saar explores gender and identity through surrealism and symbolism

- Share via

Inspired by the Parisian salons frequented by social outsiders in the 19th century, mixed-media artist Lezley Saar named her latest exhibition, on view now at the California African American Museum in Exposition Park, “Salon des Refusés.”

“I took that title and I used it to mean a salon of portraits of rejected people — people who’d been ostracized or outside the mainstream of what’s considered to be normal,” said Saar, a Los Angeles native. “I often work with themes like that, people who are anomalous with regards to race, gender or mental and spiritual aspects.”

On view through Feb. 18, 2018, “Salon des Refusés” features works from the last five years and consists of three different series: Madwoman in the Attic/Madness in the Gaze, which explores the mental realm; Gender Renaissance, which explores the physical realm; and Monad, which explores the spiritual realm.

Since the ’90s, the 64-year-old artist has worked with paint, fabric and found objects to make commentary on “hybridity, acceptance and belonging.” Inspired by a love of literature, Saar uses mixed media to depict the lives of marginalized figures and to explore Edwardian and Gothic themes. After creating book covers and illustrations for writer friends, Saar began crafting altered book works carved out of old books and containing her own paintings, dioramas and collages.

“I like the idea of a painting sucking you in like when you really get sucked in by a good book,” she said. “I use that kind of metaphor as a vehicle for doing my art.”

A common theme in Saar’s work is identity, inspired in no small part by her “neurologically atypical” transgender son, who has been transitioning from female to male for the past five years, the process of which inspired Saar’s Gender Renaissance series.

“It just got me to thinking about the ways I’ve always thought about race,” said Saar. “Just really questioning these notions of gender. Is it really what you are inside? As opposed to how you’re perceived by others. It’s been a really interesting journey and I wanted to do it from my experiences, which have been a tad surreal. That’s why there’s surrealism worked into the symbolism and imagery in that series.”

Race frequently informs Saar’s work. The artist, who grew up largely among her mother’s side of the family, is the daughter of the acclaimed black artist Betye Saar and white art conservationist father Richard Saar.

“I’ve always been this anomaly of someone who is black but looks white and I’ve always questioned the notion of race,” said Saar. “Is it how you are perceived by others or is it who you are as far as your heritage and experiences? I think it’s the latter.”

“I don’t only do portraits of black people, but usually everybody looks mixed or black or something other than white,” Saar continued. “I feel since me walking around does not present it, I can present it in my art.”

Here, the artist explains some of the CAAM portraits in her own words:

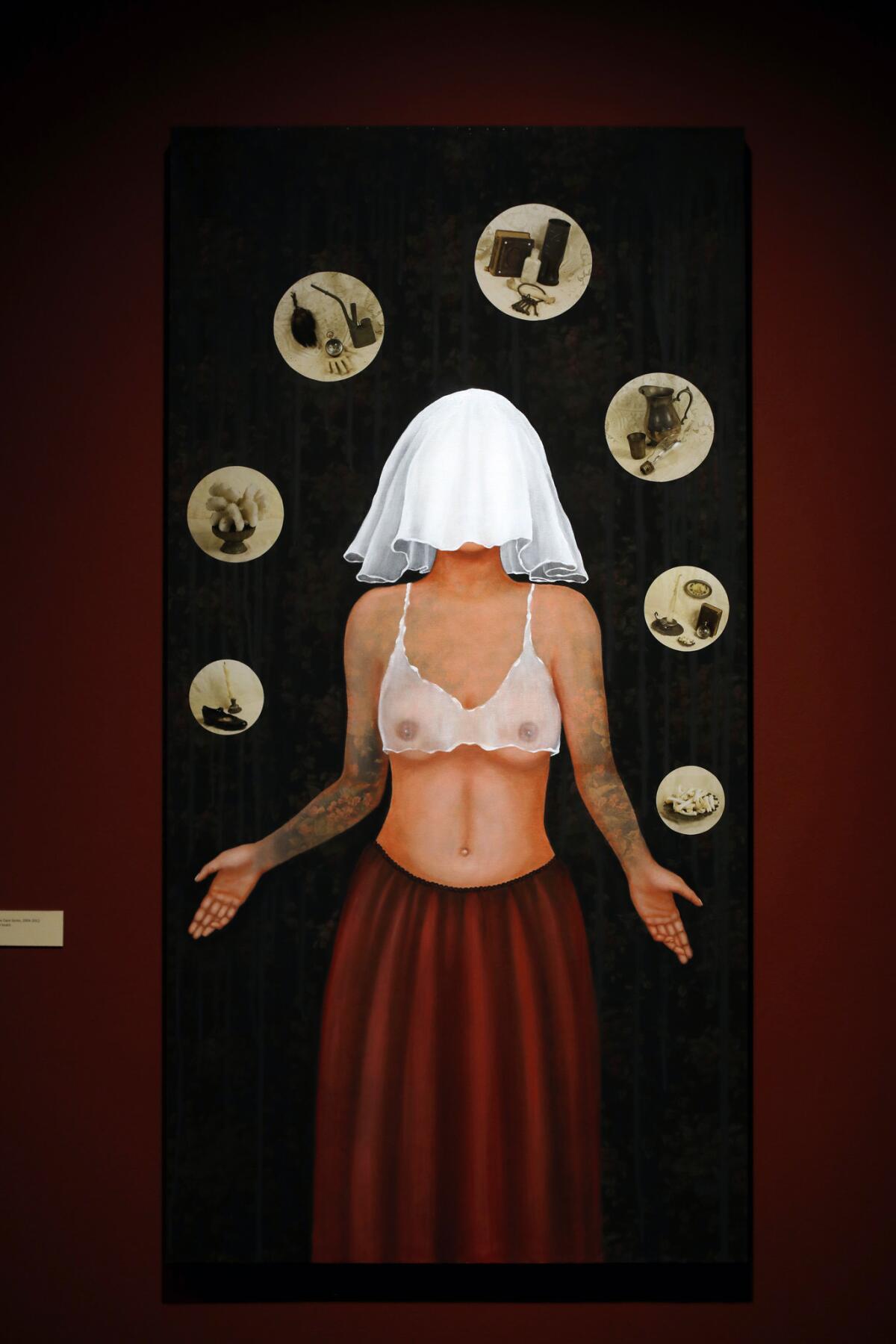

Religious Melancholia, Madwoman in the Attic/Madness and the Gaze Series

“This is one of my favorites. It’s from a series of portraits of insane female heroines from 19th century Gothic literature where I examine the diagnoses and treatments for what they considered to be insanity or madness, especially in women. They had all these poetic terms such as ‘Religious Melancholia.’ These really poetic terms that are really archaic and not used anymore. It makes you question how we describe mental illness now and when that is going to be outdated. And then the weird cures that they had like drinking water out of a skull.”

“I took these photographs of things I have in my house. They’re sort of alluding to [her] thoughts and memories: You have candles which represent life, bones which represent death, books [which represent] knowledge, and keys like the key to the answer. It gives me a lot of freedom using the medium of photography to get other thoughts and symbolism and surreal juxtapositions that maybe wouldn’t work as well if I painted them.

“She’s standing there with this veil, this sense of mystery because they really didn’t know what they were doing back then. Kind of the same way that they don’t know what they’re doing now. And she’s juggling her thoughts and her memories and maybe her hallucinations or maybe her altered realities. I always like to paint on something other than a white canvas so I’ll paint on fabric, and I used to paint on old book covers or old album covers.”

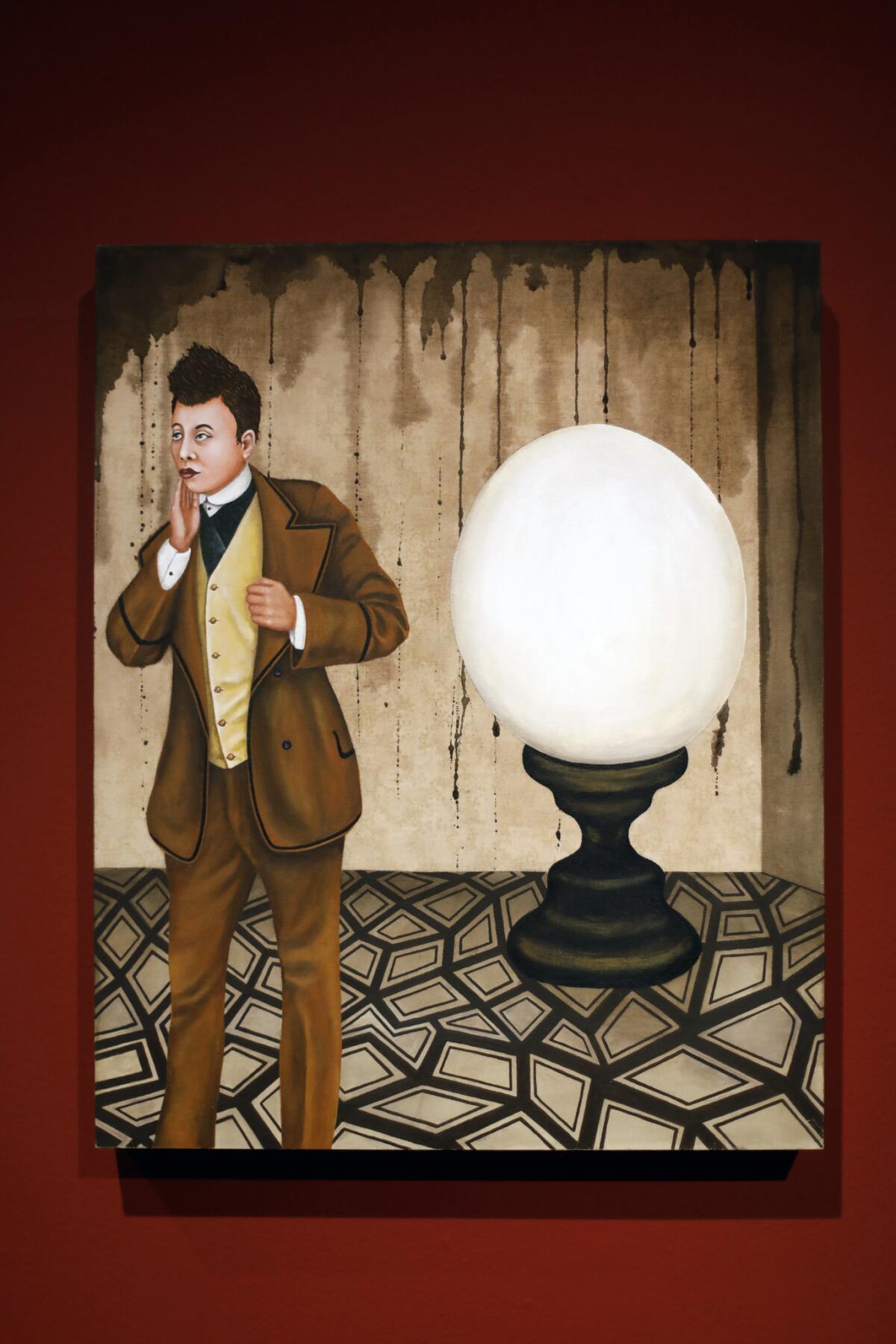

Miss Pearly, The Transcontinental Mindreader, Gender Renaissance Series

“This banner is the last one I completed. It’s from a series of portraits of people that are either transgender or gender fluid or gender nonconforming. And even though this is a very current issue, and something currently that I am dealing with, I like setting things in the past to make a current social comment because it gives it a little bit of distance and is maybe not quite as heavy-handed or corny.

“I like jumping from a really tiny scale like the Monad paintings to large [scale] just to keep my tips on fire.I like for there to be a sense of melancholy and stillness. Most of my paintings are really still. Kind of how I am. I often do portraits of people with albinism as a metaphor for myself, someone who’s black but looks white. And I just like aesthetically how they look.

“She’s someone from my imagination. I had a lot of fun sewing the banner from old trims and fabric I got at Joann’s but really giving it a look from the 19th century, the 1800s. That part’s easy and fun, the painting part is harder.”

Vesta the Johnny, Gender Renaissance Series

“This one was an actual person called Vesta the Johnny. Her name was Vesta Tilley, but Vesta the Johnny was the name she went by. She was a vaudeville performer who performed in drag. Again, it’s the upheaval, kind of throwing things upside down. It’s sort of surreal in that sense, but it’s also symbolic in the sense of birth and rebirth. Reinventing oneself.”

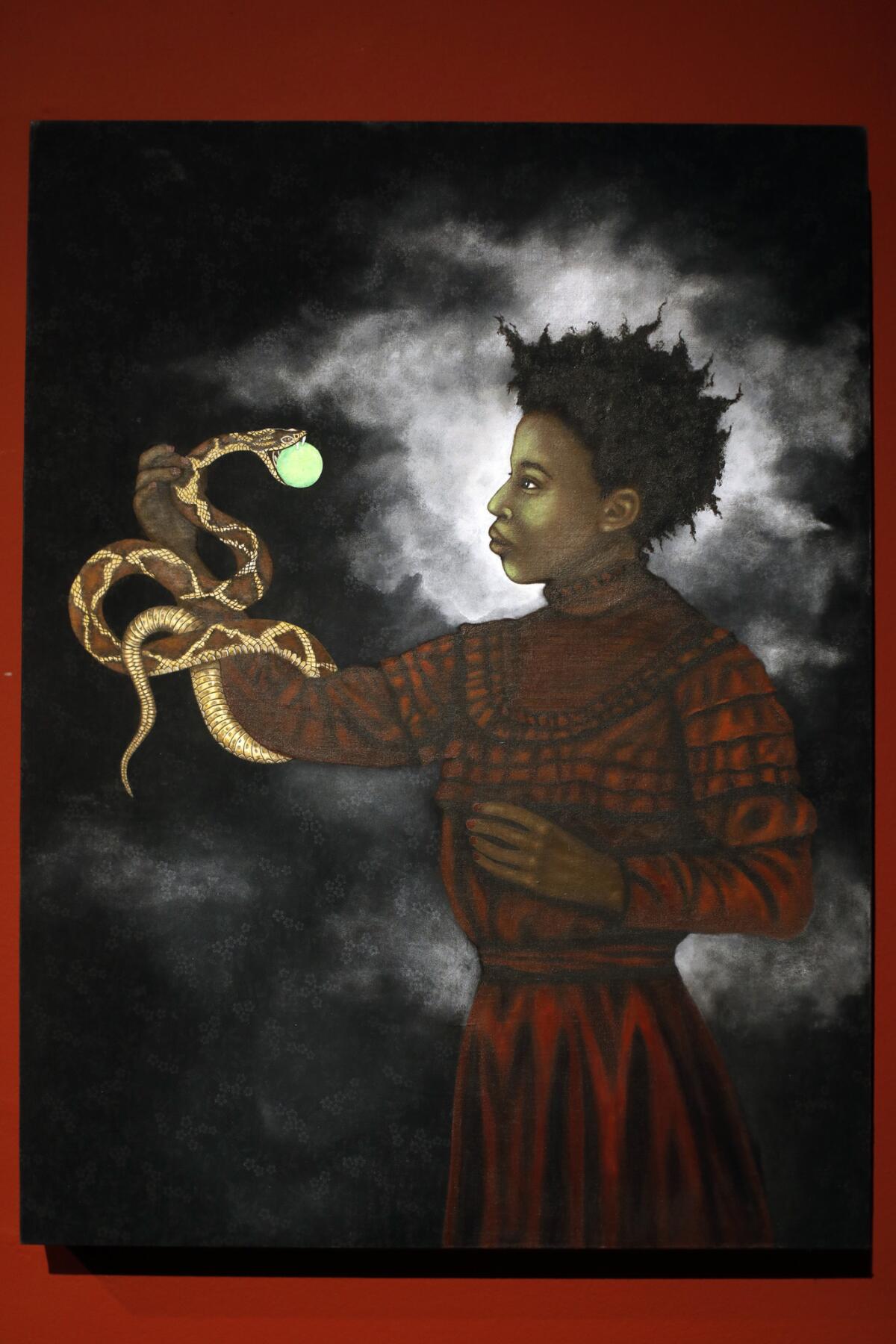

Forbidden Fruit, Gender Renaissance Series

“This one’s also one of the recent ones going more towards symbolism; the other ones are more surrealistic. I just wanted something really dark and Gothic. You don’t see a lot of that with a black or mixed perspective.

“I just wanted this sense of mystery, this mysterious stormy night and the whole symbolism of the snake which can represent so many things from fertility to death.

“In this case, with the Gender Renaissance series, it’s someone who’s gender ambiguous or gender fluid holding this snake, which represents the future. Instead of an apple it’s [holding] a glowing sci-fi orb, sort of like her looking into her future and the idea of creating oneself. The whole creativity of being trans is really interesting to me.

“I know with my kid he would get so upset if he was misgendered so instead of trying to present that literally, I do it with the surrealist imagery.”

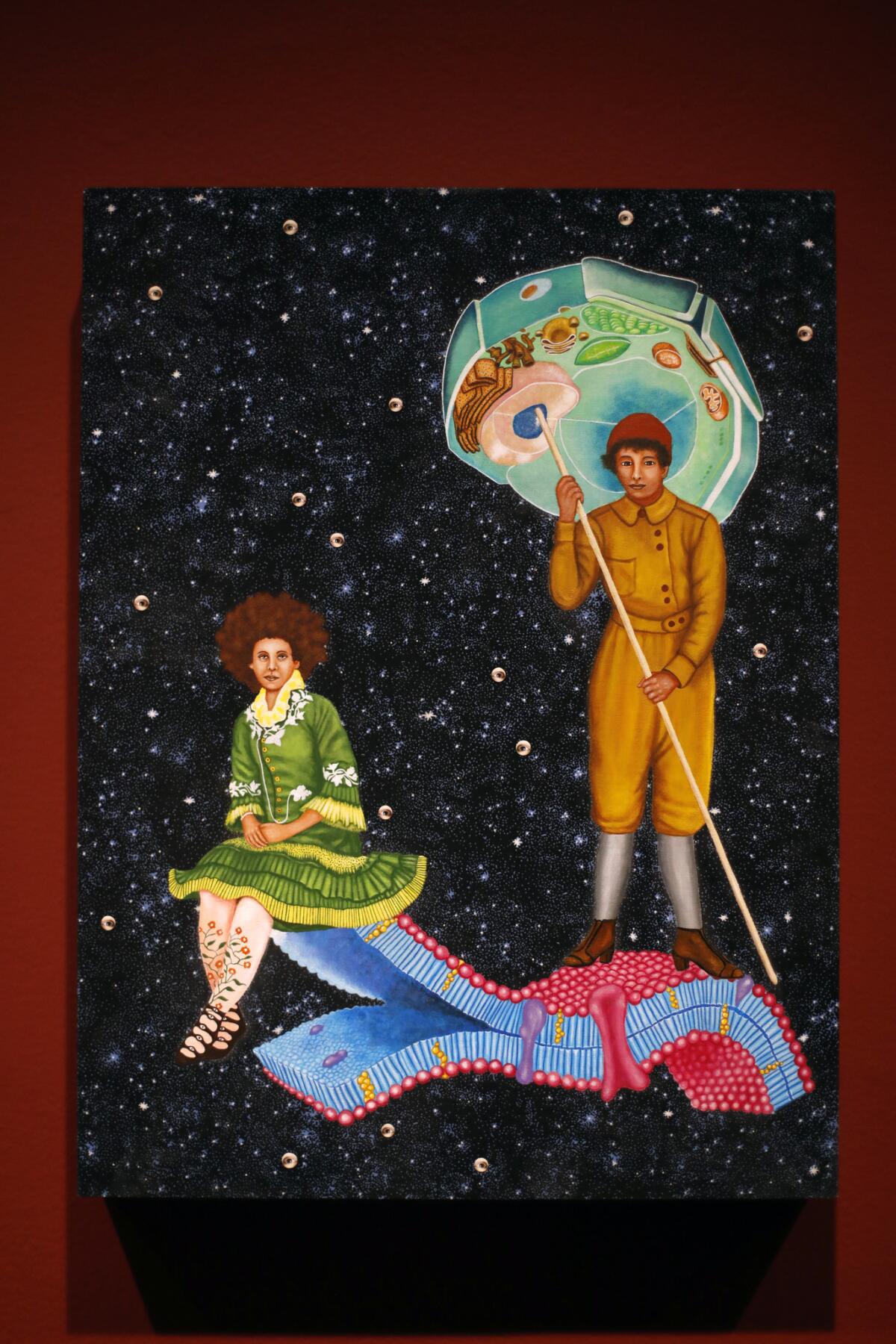

Not Born under a Rhyming Planet, Monad Series

“We sort of grew up around the occult but never really studied it. I just like exploring things that are in other realms, other realities besides the daily life, so that’s been an ongoing interest and that’s what the series Monad came out of. The whole thought about the series was this ‘As above, so below’ philosophy. So from the minutest cell of one’s body to the Earth to the galaxy and beyond, it’s the same paradigm of it being a living organism. That’s part of ancient Tibetan Buddhism.

“So reversing scale, I’ve done these hovercraft that are actually skin cells blown up to be the size of planets with people floating through the universe on them … this notion of exploration and travel and gaining knowledge.

“I wanted this series to be really bright and colorful. It’s a different palette than I usually use and I worked with these little tiny brushes with four or five hairs on them, just really getting sucked into it myself with the detail. I think a lot about what the theme is for the show [to dictate] the scale. I wanted the women to be at least the size of life or larger.”

“Salon des Refusés” is on display at the California African American Museum at 600 State Dr. through Feb. 18 from 10 a.m. to 5 p.m. Tuesdays through Sundays. Admission to the museum is free. For more information, visit caamuseum.org.

follow me on twitter @sonaiyak

More to Read

Only good movies

Get the Indie Focus newsletter, Mark Olsen's weekly guide to the world of cinema.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.