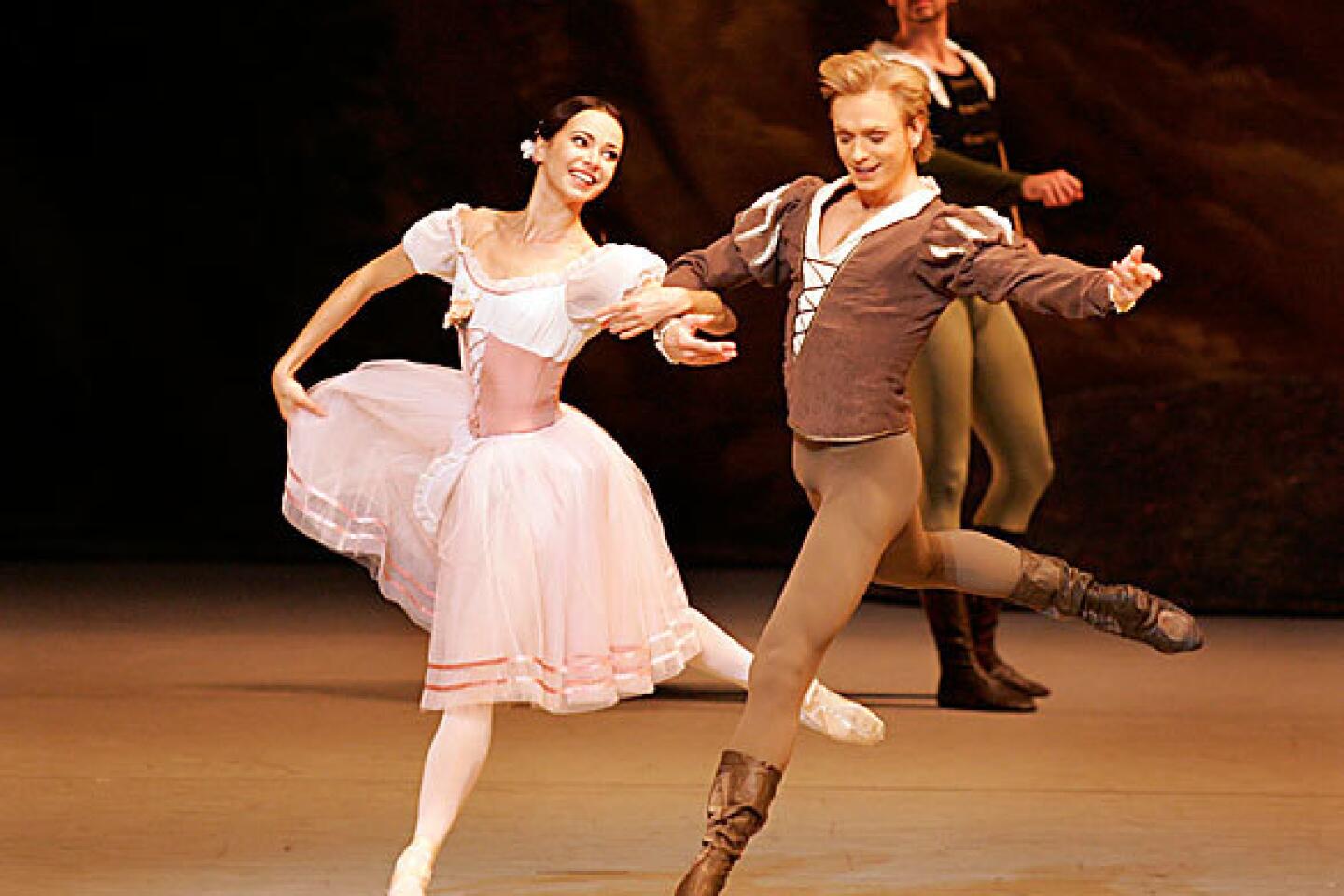

Kirov Ballet’s Diana Vishneva in ‘Giselle’

- Share via

It was a mere eight months ago that Kirov ballerina Diana Vishneva was the centerpiece of the ambitious “Beauty in Motion,” a Vishneva-and-friends show of three new works commissioned by the Orange County Performing Arts Center.

Sadly, that effort diminished her unique qualities rather than spotlighting them and left many fans testy and dissatisfied.

There were no such feelings Friday, when Vishneva was back at the Costa Mesa arts center leading the Kirov Ballet of the Mariinsky Theatre in a classical work that has become her signature.

As the doomed heroine of “Giselle,” Vishneva demonstrated her extraordinary gifts in a way no contemporary project is ever likely to showcase them.

Hers was an intuitive and highly dramatic performance, and not mistake-free. She has just returned to the stage after an injury, and at some points she was at less than full physical strength.

She bobbled a few hops on toe (pointe slippers too soft and broken, it appeared) and balked during a risky overhead lift. More unusual, she fell behind the music in the slow pas de deux of Act 2, despite a made-to-order Albrecht, principal dancer Andrian Fadeev.

These mishaps, however, failed to detract from an otherwise magical and risk-taking portrayal. Indeed, Vishneva seemed to push her performance to further extremes as the night went on.

The Kirov’s production is traditional and familiar, yet Vishneva -- and Fadeev too -- gave the impression of making up the steps on the spot, so convincing was their spontaneity and melding of physical and emotional expressiveness.

From her first sunny appearance in a pale pink dress, Vishneva’s Giselle foretold a fragile destiny. She single-mindedly responded to Fadeev’s attentiveness, emphasizing Giselle’s lovesickness. When Albrecht’s fiancée (Elena Bashenova) appeared and his deceit was revealed, Vishneva’s body collapsed not in a melodramatic mad scene but in a scary and unpredictable one.

In the second act, Vishneva’s spirit and body looked broken, and she emphasized this with an unflattering angularity. With Albrecht holding her, though, she extended her liquid-like limbs in a gravity-defying line. Her unpredictability was riveting.

Happily, Vishneva’s fellow artists matched her commitment and prowess. Fadeev’s aristocrat was used to getting his way but was also as smitten with Giselle as she was with him.

Like Vishneva, he displayed a bold technical clarity, but not used for its own sake. With the exception of that one off-kilter lift, he enabled Vishneva to take chances, and he responded in kind.

He was well matched by Dmitry Pykhachev as Albrecht’s rival, Hans (a character normally named Hilarion). Pykhachev is a sleek, elegant danseur, not the rough-hewn fellow that Hans is in other productions.

He is customarily a simple hunter who drops a rabbit at Giselle’s doorstep. Here, he brought flowers as a courting gift. Pykhachev made the class rivalry with Albrecht real, and the performance was stronger for having such a vivid love triangle.

It was a more fitful night for the corps de ballet, which was alternately breathtaking and flat-footed. An overemphasized downbeat in the arabesque hops made these slim ladies clump across the stage.

Ekaterina Kondaurova was the imperious but highly feminine Myrtha, queen of the Wilis. She conjured the impression of a floating ghost with the tiniest of bourrée steps on toe. Every time she raised her arms overhead, the perfect oval she formed framed her face like a cameo.

Elena Sheshina and Philip Stepin fumbled their way through the first act peasant pas de deux in a below-par performance. They managed to eke out the bravura steps but with great effort and fear written across their faces.

The production (with sets by Igor Ivanov) was serviceable, its costumes (by Irina Press) merely plain. The company has abbreviated the mime sequences and gestures, leaving out some key information about the risks of dying with a broken heart.

Still, there was no misreading Vishneva or her fellow principals. Their artistry was universal.

More to Read

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.