‘The Line: A Novel’ by Olga Grushin

- Share via

The Line

A Novel

Olga Grushin

A Marian Wood Book/Putnam:

324 pp., $25.95

Queues were a conspicuous feature of the old Soviet economy and its distributive malfunctions. Long lines would form when word came that some scarce item was about to go up for sale. Nobody knew what it would be -- gloves, boots, toothpaste -- but people lined up anyway, hoping they could use whatever it was, and that it wouldn’t have run out when they got to the front.

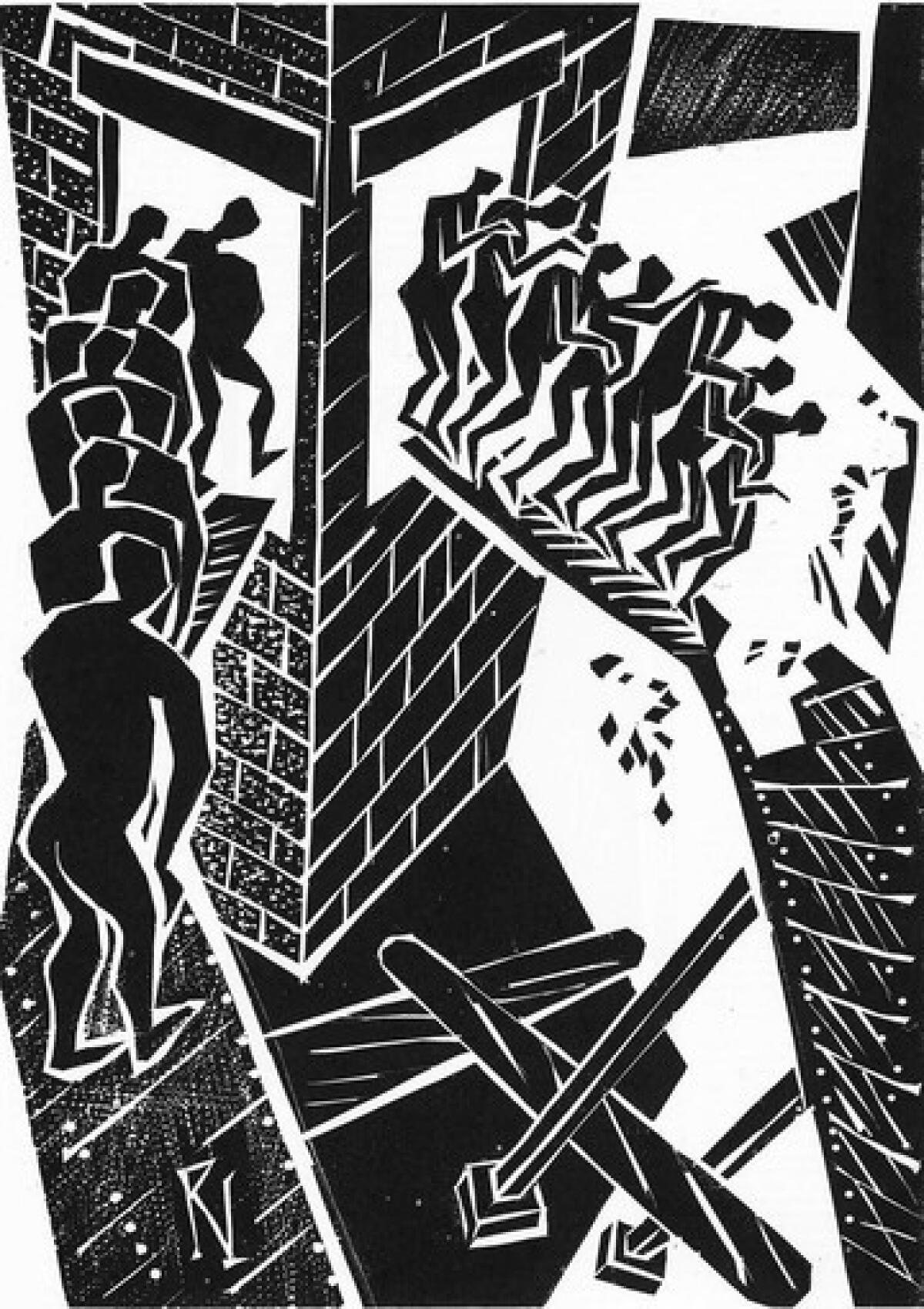

In “The Line,” Olga Grushin uses the queue as a symbol of the wider nightmare aspects of life under Stalin and the 30 years, only slightly looser, between his death and the advent of Gorbachev and perestroika.

Four years ago, Grushin, born and largely raised in Russia and long living in the United States, published the widely praised “The Dream Life of Sukhanov.” It told of an idealist artist who became a top enforcer of Soviet cultural dictatorship, only to lose his job when the official line switched to ordering freedom instead of punishing it. The currency Sukhanov had sold out for was suddenly worthless; the private shame that ate at him all those years gave way to a series of surreal dream states.

‘Sukhanov’ successor

“Sukhanov,” a finalist for a Los Angeles Times Book Prize and Britain’s Orange Prize, is remarkable in many ways: first, for the acuteness with which it satirizes the collapse of the regime’s hollow grandees; second, in its Gogol-like mix of irony and compassion for the protagonist. And finally, for Grushin’s mastery of an English prose style whose only hint of the acquired was that it was occasionally overdressed. The dream states were a much more troubling defect, overwritten to the point where they seemed generated less from the dreamer’s extremity than from the writer’s self-indulgence.

“The Line” is a lesser effort, lacking much of its predecessor’s strength and exacerbating its defects. Its best feature is the device of the queue, and Grushin presents it as a sinister bait-and-switch, in a series of tingling variations that suggest Kafka a little and the eternally non-arriving Godot a great deal.

The device’s aim is worthy enough: to show the distortions of ordinary Soviet life. But this ordinary life is diffuse and lacks the ironic focus that Grushin had found for the updraft and downfall of her uneasy bureaucrat. Among the family at the center of “The Line” there is no one with the tragicomic substance of Sukhanov. And the prose is more garishly attired, the dream states more unmoored.

Grushin’s protagonist family consists of Sergei, a tuba player in a state band that blares marches at parades and celebrations; his wife, Anna, a teacher; their son Alexander, a loutish youth who cuts most of his college classes; and the grandmother who, in pre-revolutionary days, studied dance in Paris, performed in three ballets by the soon-to-be world famous Selinsky, and was briefly his mistress.

Selinsky, long exiled from the Soviet Union and denounced by its cultural authorities, is of course modeled on Stravinsky. And the queue that Anna sees forming one day, and joins, is whispered to be for a concert the following year by Selinsky, who is to be invited back. (Stravinsky, then 80 and having left the country half a century before, did indeed give concerts in Moscow and Leningrad in 1962. Grushin notes in an afterword that the line for tickets in Leningrad formed a year in advance, with people taking turns waiting.)

If Stravinsky’s appearance was real, Selinsky’s is a rumor, and ultimately less than that. Nevertheless, some 300 music-lovers queue up through winter, spring and fall at the kiosk where the tickets are supposed to be sold. It remains shuttered for months; when it does occasionally open, the tickets are for the kitschy folklore groups favored by the authorities. Yet the Selinsky devotees remain. Grushin uses their maltreated passion for great music as the sign of an inner authenticity never quite corrupted by the regime.

Sergei, Anna and Alexander all take turns in the line, their motives fluctuating. Sergei, ashamed of his schlock performances, has a secret passion for real music; this transforms into a passion for a woman in the line to whom he hopes to give his ticket. Alexander wants the ticket to sell; later, a series of visions ignite a dream obsession with Selinsky. Anna, selfless, plans alternately to give the ticket to her mother and to Sergei.

Most of the novel follows each of the three through extravagant, often hallucinated encounters, misadventures and Leningrad wanderings. The plot takes massive kaleidoscopic turnings and recombinings, the picaresque is piled on to stifling effect, while the characters, for all their jangled activity, remain pallid.

Soviet existence

It is the queue, rather than those who join it, that is distinctive. In one sense it is of a piece with the rest of Soviet life: futile activity, with traps implanted (as the queue will turn out to be) by a paranoid regime. But in another, it is a liberation. Grushin, at her best here -- as well in gritty evocations of Leningrad’s weathers, streets and street life -- writes of it beautifully.

If regular existence is purposeless and without hope, the queue’s purposelessness offers a hope, however illusory, that momentarily transforms. It gives those who stand in line an unaccustomed lightness and, escaping the daily grind, a sense of freedom. And over the year, organizing themselves by number, holding a neighbor’s place to allow brief absences, quarreling or befriending each other, a community forms. Not the top-down community imposed by the system, but one that takes shape, however short-lived and fragile, from the bottom up.

Eder, a former Times book critic, was awarded a Pulitzer Prize for criticism in 1987.

More to Read

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.