Greg Critser considers our mortality in ‘Eternity Soup: Inside the Quest to End Aging’

- Share via

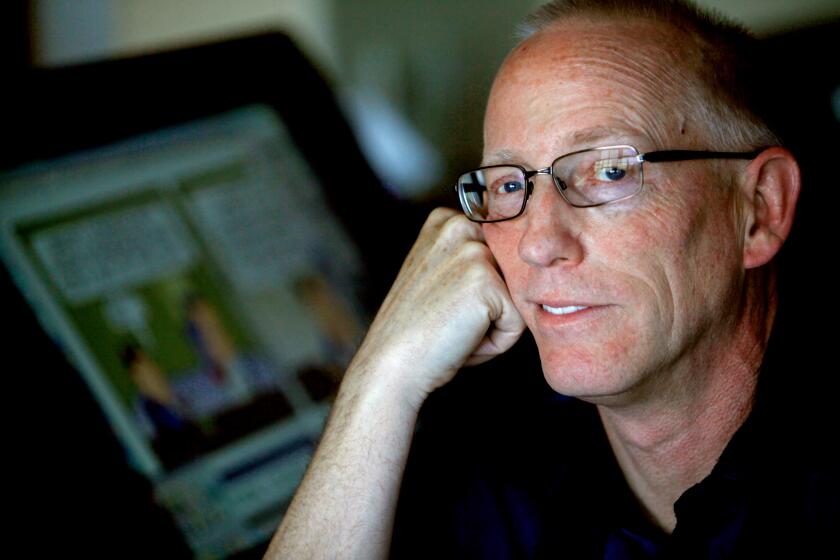

“My American pathology trilogy,” Greg Critser calls it: “Fat Land: How Americans Became the Fattest People in the World” (2003), “Generation Rx: How Prescription Drugs Are Altering American Lives, Minds, and Bodies” (2005) and the just-released “Eternity Soup: Inside the Quest to End Aging.”

These books tell the stories behind our greatest fears and obsessions. The stakes are high: health, happiness and the pursuit of immortality.

And yet, Critser is profoundly modest. Each book begins with a personal quest. He was fat; he has battled depression; sometime in the last decade he began to feel as if he was slowing down.

Questions about how to handle (and reverse) these changes led him down a three-year rabbit hole to research the world of calorie restriction, hormone replacement therapy and even organ replacement and tissue engineering.

Critser lives with his wife and two dogs in a beautiful Pasadena Craftsman -- all muted colors, wooden floors, hand-woven rugs, overflowing bookshelves, flowers and leaded panes. There are rooms to read in, a big wraparound porch, bottles of homemade liqueurs and eau de vie.

In the back is a small office he calls his laboratory, though he rarely writes there. It’s full of bikes, guitars, a drum set and the books used in his research. A terrarium holds a Mexican salamander, which can regenerate its own limbs.

Regeneration is a subject that fascinates Critser and will be the subject of a future book. But he is full of ideas: The line is long and life is, well, short.

“Eternity Soup” is packed with characters -- scientists and snake oil salesmen, true believers and skeptics. Critser met his mentor on the subject, USC gerontologist Caleb Finch, at a gathering of the Calorie Restriction Society in Tucson: “We were both looking for something to eat.”

Once a history major at Occidental College, Critser has always been fascinated by medicine and science. His father worked in the aerospace industry, but his great grandfather (who lived to be 91) was an “autodidact; an apothecist and an architect.” (He still has a bookshelf of his great-grandfather’s books -- fittingly, Poe and Stevenson.)

Critser, though, always preferred the interview to the clinical trail. His lab days ended early: When he was 8, growing up in Whittier, he and his best friend did some experiments that blew out all the lights in the house.

So Critser became an editor at magazines, including Buzz. Sometime in the early 1990s, he noticed a photograph of a woman jogging and pointing at a sales chart while taking care of children -- it was an ad for the antidepressant Paxil.

For Critser, this was a symbol of the way consumers had been sold medical culture, told what was acceptable disease and what was not. He wrote about the pharmaceutical companies for Harper’s and thus began his career as a journalist interested in the stories behind the stories -- in our willingness to override our instincts and healthy skepticism.

It was his mother, an advertisement for informed, healthy aging, who over lunch in Palm Springs told Critser that aging was unnatural. Yet resisting it, either with supplements or hormone replacement or even lifestyle changes like yoga, is something only the wealthy can afford.

In the course of his research, Critser says, what most irritated him was the incessant effort to sell, sell, sell.

“I tried to give them the benefit of the doubt,” he says of some of his subjects, “but they saw me as a big party pooper. Part of me is just suspicious of money, suspicious of the selling. One of the things that few people talk about is that we have a society in which classes are aging very differently. The middle and upper classes in this country have a 50% better chance of becoming centenarians.”

Critser has been studying Jessica Mitford’s papers and would like to write a book on death and the ceremonies surrounding it -- that would make his trilogy into an even quartet. He is fascinated by social death, the celebrity funeral and the relatively recent practice of holding celebrations of a life instead of funerals.

He’s been thinking about perseveration (a form of cognitive inflexibility) and perseverance; about the biology and genetic dispositions of cities (New York, Los Angeles and Mexico City).

But he is discouraged by the shrinking market for the printed word.

“These books cost money,” he says. “You have to travel; one of the most important functions of a journalist is to bear witness. You can do some amazing mining on the Internet, but you have to visit the people doing the work.”

Critser experimented with some of the products and therapies he encountered, though as an accomplished cook (“my very own chemistry experiment”), he did not get far with calorie restriction.

He found that taking testosterone had modest benefits -- a little more energy, a little more cognitive flexibility.

But perhaps more than any of the theories in “Eternity Soup,” he seems to have taken the lesson of George Johnson, who lived to the age of 112. His secret? He was surrounded by young people. He socialized a lot.

Critser and his wife do not have children, but their house is often full of visitors: “I try to cram my literary tastes down my nephews’ throats.” Their home is a testament to intellectual curiosity -- music, food, art, books.

He makes a lunch of rigatoni and a simple salad of crisp yellow and orange peppers, then offers a taste of one of his concoctions, Latte di Suocera: Mother-in-Law’s milk, made from grappa, milk, vanilla, sugar and lemon juice.

Critser’s imagination was captured early in the research for “Eternity Soup” by Alvise Cornaro’s “How to Live One Hundred Years,” a book written in 1558. In it, Cornaro advised sobriety, temperance, regularity and calorie restriction. He swore by a daily broth made from capon, egg and bread.

Critser includes five versions of this staple in “Eternity Soup.” A little broth, a little Mother-in-Law’s milk, and it might not be so bad to live 100 years.

More to Read

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.