Words of Wisdom: Let It Be

- Share via

TUCSON — The cult of the mysterious KCDX-FM started innocently enough.

Bill Keeling, a 51-year-old respiratory therapist, found the Arizona radio station when his daughter fiddled with his car stereo. Lynn Richeson, a graphic designer, fell in love with it when she heard a song for the first time in 30 years. One man became an acolyte after he rented a car in Phoenix and all the radio buttons were set to 103.1.

For the record:

12:00 a.m. May 5, 2006 For The Record

Los Angeles Times Friday May 05, 2006 Home Edition Main News Part A Page 2 National Desk 0 inches; 28 words Type of Material: Correction

KCDX-FM: Monday’s Column One about eclectic Arizona radio station KCDX-FM referred to its playing a 1960s Fabulous Poodles song. The group, however, did not record during the ‘60s.

The signal, which started broadcasting throughout central Arizona and much of Phoenix in 2002, played an eclectic mix that included hits by Huey Lewis and the News and an obscure 1971 tune about cannibalism by the Buoys. There were no commercials, no DJs, no way the station made money.

Hundreds of e-mails filled KCDX’s inbox each week. Who was choosing the playlists? How did the station survive without advertising?

“IF YOU NEED DONATIONS, CONTACT ME, PLEASE,” one listener wrote. “A day without KCDX is like a day without sunshine,” another said.

The fans found one another online, sharing their frustrations about other stations that played the same songs over and over, and recalling the first time they heard “Pinball Wizard” or a forgotten song by Duran Duran.

They spent hours speculating about who owned KCDX. Richeson, Keeling and others scoured the Internet to identify the person who referred to himself on the station’s website only as “The Guru.”

But the harder they pressed for answers, the more frightened the Guru became, until he began questioning the wisdom of what he had done.

*

Fifty years ago, thousands of independently programmed stations similar to KCDX filled America’s FM dial. Their disappearance, and the passion of KCDX’s fans, demonstrate how greatly radio has changed and how much listeners may be missing.

Until the midcentury, commercial radio was focused almost solely on the AM band. FM signals, which don’t travel as far as AM, were in such little demand that they could be snapped up by almost anyone with a little technical know-how and business savvy.

When rock ‘n’ roll emerged in the mid-1950s, it was ignored by most AM stations. Soon, disc jockeys named Wolfman Jack and Murray “the K” began filling FM airwaves with electric guitar solos and B-side tracks. Then the nation’s youth discovered rock, and FM radio’s audiences and advertising exploded.

By 1979, when FM finally surpassed AM in audience size, it had become not only a big business, but a competitive one. Stations turned to market researchers to find out which songs record buyers liked and what concerts they attended. DJs discovered that if they chose playlists based on such data instead of instinct, fewer listeners changed the dial.

Soon, the same popular tunes began dominating playlists everywhere. Whereas rock stations in the late 1960s played up to 2,000 different songs a month, some pop stations today play as few as 350 and the most popular tunes can be heard as frequently as four times an hour.

“Before the 1970s, everything was driven by a DJ’s emotions,” said Lee Abrams, an early researcher and now chief programmer at XM Satellite Radio. “If it was raining, you heard two hours of rain songs. If the night guy didn’t like Jethro Tull, you never heard it after 6 p.m. We brought some discipline to choosing playlists.”

*

Free-as-a-Bird Format

There is no discipline at KCDX, where the song choices are as chaotic as a schoolyard at recess.

And that made the station’s fans curious. They marveled at the musical juxtapositions. Where else could one find Foreigner’s “Dirty White Boy” after Elastica’s “Connection”? Could it get crazier than a string of songs by Diesel, the Moody Blues, Chilliwack, “Space Oddity” by David Bowie and then “Finish What Ya Started” by Van Halen? Big Head Todd and the Monsters following the Beatles and Deep Purple?

“I remember listening to those songs when I was a teenager,” said Maureen Kane, 52, a lawyer who became a devoted KCDX listener after she heard a 1960s Fabulous Poodles song. “It makes me feel so happy when I can remember that time when I’m driving to work.”

In chat rooms and whispered conversations, some fans speculated that the playlists contained hidden messages. Was the Guru trying to say something when he played 12 Rolling Stones songs in a row? Was it Republican or Democrat sensibilities that put the 1970s pro-drug anthem “Little Green Bag” alongside Fleetwood Mac’s “I’m So Afraid”?

As those debates raged, listeners began noticing that between B-side tracks by Bachman-Turner Overdrive and Pablo Cruz, a Federal Communications Commission-mandated identifier occasionally intoned: “KCDX, 103.1 FM, Florence, Ariz.”

Based on that scrap of information, a Los Angeles musician named Adam Marsland drove to Florence, population 5,800, to find KCDX’s owner.

When Marsland showed up, the Chamber of Commerce president said he had no idea who owned KCDX. The station’s tower wasn’t even in Florence, the president remembers telling Marsland, before showing him evidence that he wasn’t the first to come looking: a box full of thank-you cards, bills in small denominations, even a cake.

Cars in Phoenix and Tucson began sporting KCDX bumper stickers that one fan printed in her garage. Someone else made a T-shirt reading “KCDX: What’s Next?” Listeners from as far away as Washington state and Montreal tuned in online.

The fans’ enthusiasm was matched by their dismay that playlists at other stations had become so bland.

Yet industrywide, that was the key to higher ratings, partly as a result of how ratings are tallied. Most stations rely on Arbitron Radio Ratings and Media Research to measure audience sizes, which determines advertising rates. Arbitron, in turn, relies on volunteers filling out diaries listing the stations they hear each day.

Studies show that listeners have trouble remembering more than three stations at a time. So programmers focus on making stations more memorable, rather than musically interesting.

No wonder so many stations go by clever call letters such as KPOP, KISS and KFOG.

*

Fans Seize on Mystery

KCDX isn’t clever. The call letters don’t mean anything at all. But the station’s uniqueness inspired its fans, like residents of Oz pursuing the Wizard, to unmask the Guru.

Fans began requesting copies of KCDX’s licenses and scouring the Internet for clues. Eventually one of them found the owner’s name on a yellowed form: Ted Tucker. Another found an address. A third listener, named Tim Jehl, who became a KCDX fanatic after hearing Loudon Wainwright III’s “Dead Skunk,” found documents indicating that Tucker owned several other stations through a company named the Desert West Air Ranchers Corp.

“I don’t want anyone to think I’m some kind of stalker,” said Richeson, the graphic designer. But she admits she made a hobby of finding information about Tucker. “I think he’s from back East. I know he’s married.”

More details emerged: Tucker had trained to be a pharmacist, but taught himself broadcast engineering through a correspondence course. He put his first station on the air in 1986 and sold it two years later. In the late 1990s, he started KCDX and began broadcasting Spanish-language music. In 2002, he moved the call letters to another station and started playing obscure rock.

Tucker could afford the indulgence: In 2004, he’d sold a station in the Phoenix area for $18.5 million. But throughout his career he has shunned attention, cloaking his identity behind corporate titles and unlisted phone numbers.

That didn’t stop KCDX’s fans, who wanted to show their gratitude.

“My whole youth is contained in songs that other stations don’t even play anymore. It’s like commercial radio thinks I don’t matter,” said Stan Brown, 55, a Scottsdale, Ariz., audio engineer. “Then this guy starts playing the songs I love. I just want to thank him.”

Some wrote Tucker letters. One man proposed a way for listeners to pay him a monthly tithe.

All the while, the Guru watched warily from a distance.

*

Man Behind the Music

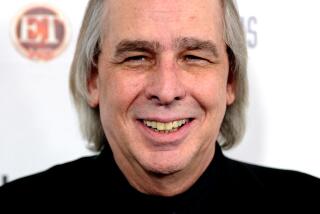

Tucker won’t tell people his age, but his graying hair suggests he’s seen a few classic rock acts before they were classic. He won’t say where he was born or where he lives. He’s soft-spoken, prefers jeans and Hawaiian shirts, and is the kind of thrifty millionaire who takes his leftovers home from restaurants. He chose the moniker “The Guru,” he said, almost on a lark.

He has always been fascinated by what he calls “the physics of radio.” For years, he fed his love of music by collecting first albums and then FM stations. He still owns more than half a dozen signals, he said in a rare sit-down interview at a Tucson restaurant, even the name of which Tucker prefers to keep secret.

With KCDX, Tucker says he didn’t intend to challenge any orthodoxy. He had to broadcast something or else he would lose the license, so he uploaded his personal library.

“There’s something kind of cool about hearing the song I chose play on the radio,” he said. But he prefers not to say anything at all.

Tucker is the last of a breed. In the 1990s, Congress relaxed the federal rules that had limited the number of stations a company could own. A surge of Wall Street money and consolidation followed, pushing up the value of stations like Tucker’s until almost every license was snapped up. And that made station executives more cautious about what they played.

“There is nothing that retards the innovative process like having to increase profits every 90 days,” said Rick Cummings, a radio division president at one of the nation’s largest broadcasting companies, Emmis Communications.

Tucker concurs, but he doesn’t necessarily think it is a bad thing. At all of his stations besides KCDX, he has embraced the science of data-driven playlists. In the Arizona cities of Nogales, Sierra Vista and Douglas, his stations are programmed by far-flung consultants.

“I sympathize with people who are angry about how bad commercial radio is now,” Tucker said. “But look at how people dress, what movies they watch. If you want to make money, you have to aim for the lowest common denominator. There’s nothing wrong with that.”

As long as you have an alternative, that is. The Guru acknowledges that part of the reason he continues spending about $200,000 a year to run KCDX is so he can listen to the songs he loves.

There are no hidden messages in the choices, no master plan. In fact, there is hardly a station at all: Although the KCDX license is technically based in Florence, the broadcast tower is 55 miles away on a dusty hill in the even-smaller town of Globe, Ariz.

The songs are in a massive digital server an additional 88 miles west in Phoenix. Nobody knows how many listeners tune in, and Tucker isn’t interested in paying Arbitron to find out.

When Tucker and his son plan a road trip, they’ll choose a playlist in advance by sending instructions to the server over the Internet (KCDX has no employees). Otherwise, they let the computer choose tunes at random.

The proof that Tucker may have stumbled onto something can be found not just in the fervor of his fans, but in so-called “Jack” format stations that began appearing nationwide last year. The stations’ playlists contain thousands of songs spanning decades and have spawned imitators, including the country-focused Hank-FM and, for female audiences, Jill-FM.

For a while audiences tuned in. But even that growth is slowing. The problem, some executives say, is that although these formats are more unpredictable, they haven’t gone far enough. They haven’t gone as far as KCDX.

*

Unsettling Attention

In Internet chat rooms, KCDX listeners have made Tucker into an icon. And they have forced him to face their affection.

One day, an e-mail arrived at KCDX from a man who said he found out that his wife of six years was cheating on him. He had decided to kill himself, and was sitting with a gun in his hand when the clock radio turned on and KCDX filled the room with Chicago’s “25 or 6 to 4.” He reconsidered his decision. Tucker, he wrote, had saved his life.

Another fan mailed a complicated model he built out of wood and a special glue he manufactured from his own hair. Others began calling Tucker’s house and interrogating whoever answered.

One night a listener who found Tucker’s address on KCDX’s federal licensing agreement walked across his cactus-strewn lawn and knocked on the door. Tucker, who was spending a quiet evening with his family, confronted the man. What could be so important, he asked, to justify such an intrusion?

At first, Tucker had enjoyed answering fans’ e-mails about the music. Now, though, the Guru was spooked.

“I don’t know why all these people want to figure out who I am,” he said. “I didn’t create KCDX to prove anything. These people treat KCDX as if it can change the world. It can’t.”

So now, Tucker is thinking of leaving Arizona. He bought a home in another state -- he’d rather not say which one -- and if someone offered him the right price, he would sell KCDX tomorrow, he said.

Like other gurus, Tucker has had to consider the repercussions of changing people’s lives. The fans love him and venerate what they think he stands for. But Tucker never meant to stand for anything.

The cult is growing, but the Guru doesn’t want to lead it.

“I hope I don’t regret having started this thing,” he said. “We can’t change what radio has become.”

More to Read

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.