Early terrorist in U.S. condemns today’s jihad

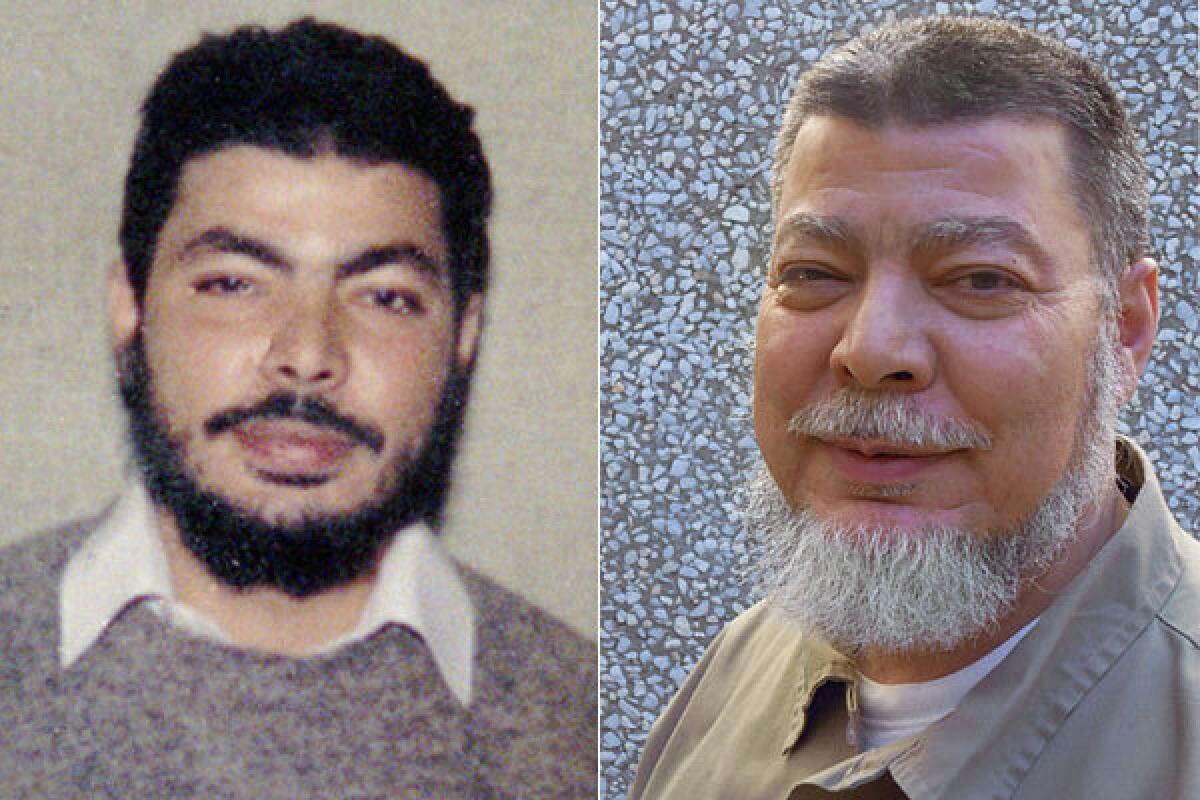

El Sayyid A. Nosair, imprisoned for the murder of Rabbi Meir Kahane and the first World Trade Center bombing, reaches out to a reporter to say he wants peace — and his freedom.

- Share via

Long before Sept. 11, the war on terrorism and two pressure-cooker bombs at the Boston Marathon, a young Muslim from Egypt walked into the ballroom of a New York City hotel and shot to death an outspoken Jewish rabbi.

El Sayyid A. Nosair, authorities say, was the first Islamic jihadist to commit murder in the United States. He later helped plot the first World Trade Center bombing from behind bars in 1993 and conspired to target the bridges and tunnels leading in and out of Manhattan.

Now serving life in prison, he has been out of the public eye for years.

But last fall, Nosair emailed me after reading a story I wrote about government secrecy in the prosecution of the Sept. 11 plotters. He wanted to talk about his religious beliefs, the crimes of his past and his attempts to win his freedom.

He said he condemns jihad as it is practiced today. Young men are throwing their lives away, killing innocents, he said. The families of the jihadists suffer for years, he said, something he has learned after more than two decades in prison.

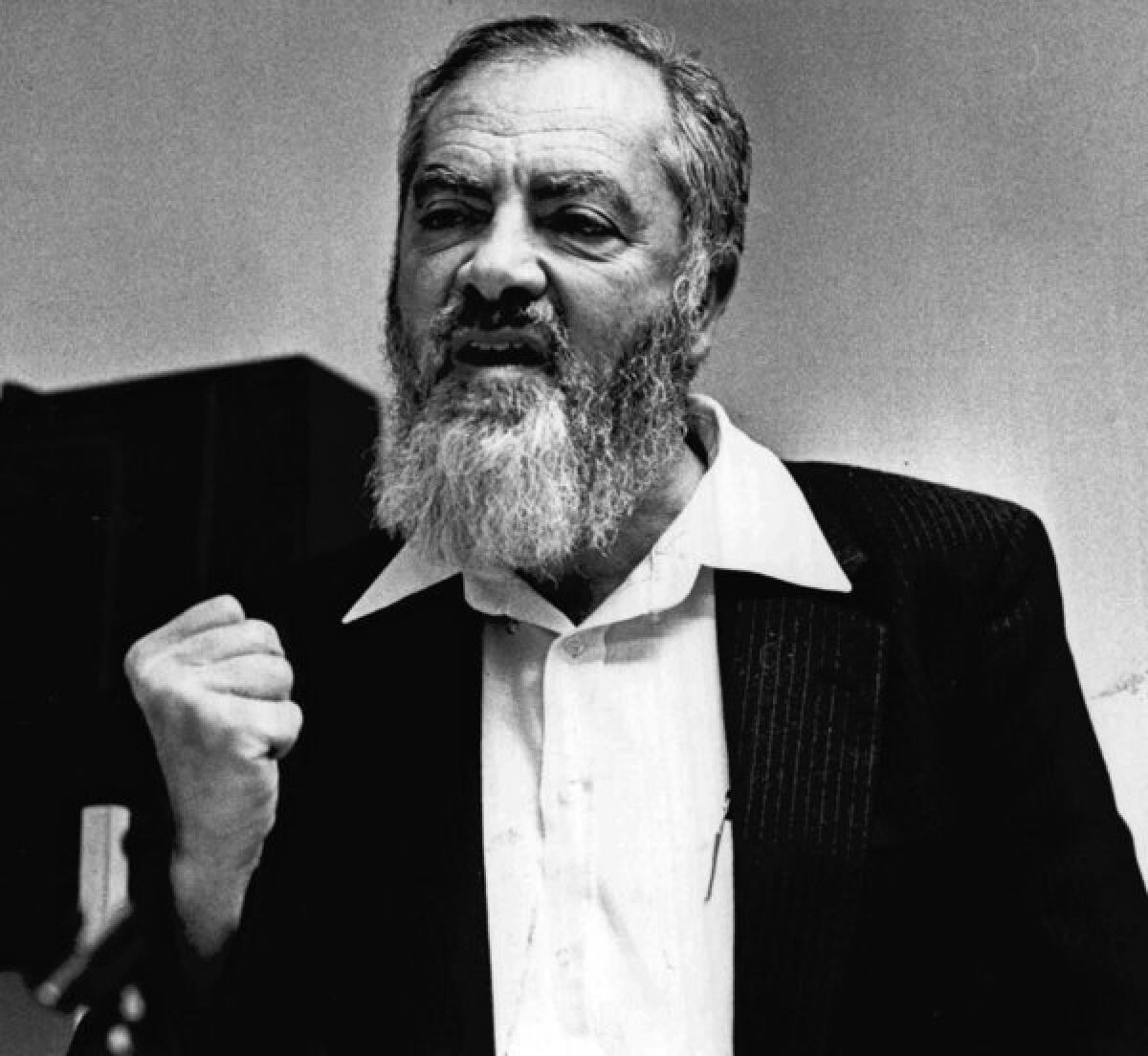

In more than 60 emails, letters and phone interviews, he offered no regrets for the murder of Rabbi Meir Kahane in 1990. That killing, he said, was justified because the rabbi had called for war against Muslims. Kahane, founder of the ultranationalist Jewish Defense League, "openly advocated genocide and ethnic cleansing," he said.

But he warned some of the young men who have followed in his footsteps that killing bystanders, whether in New York or Boston, does nothing to further the cause.

"There is a difference in the 'passion' that jihadist young men aspire to today and what I was trying to accomplish back in the late '80s and early '90s," he said.

"Unfortunately," he wrote, "these kinds of acts will continue as long as the U.S. administrations continue, one after another, with unjust policies and acts imposed over the Muslim world."

Rabbi Meir Kahane, founder of the ultranationalist Jewish Defense League, was shot dead by El Sayyid Nosair in a Manhattan hotel ballroom. (John Prieto / Denver Post) More photos

If he could reach the younger jihadists, he said, he would counsel restraint. "Seek help in patience and prayer," he said, quoting the Koran.

Most important, he said, he reached out to me with the hope that by speaking out he could use his notoriety to help end the centuries-long unrest in the Middle East, where he believes in the two-state solution of Arabs and Jews living in peace. He said that when he was a youth his family was driven from their Egyptian village by "Israeli aggression," and his anger over that banishment ultimately led him to prison.

"It is my desire to form a connection with you," he said, "whereby we can do some things together for a lasting change and a viable solution."

Nosair is also trying to mount a case for freedom. Despite a confession to the FBI in 2010, he now says he really didn't kill Kahane, but was only present at the slaying. Despite the detailed evidence in the World Trade Center conspiracy case, he says the bombers themselves, not he, were the masterminds.

None of his claims, or his admonitions to modern jihadists, have any credibility with prosecutors.

Andrew C. McCarthy, who led the team of federal prosecutors that sent Nosair to prison, said in an interview: "He'll never get out. He's never going any place."

Nosair, now 57, has spent more than 22 years in prison, much of it in solitary confinement. Photos he sent show him with graying hair and an expanding belly.

Nosair's wife divorced him long ago; he has not seen his family since 1995. One of his sons, who was 7 when his father went to prison, has traveled the country denouncing him in public lectures.

In those early years behind bars, Nosair was regarded as a highly dangerous inmate with "substantial influence over the Muslim populations at the various United States penitentiaries," prison records showed.

He has led prison demonstrations in which he and fellow Islamic inmates screamed and banged on their cell doors, and was indirectly involved in a prison killing carried out by Sunni Muslims, according to the records. He has threatened other inmates in attempts to convert them to Islam.

Port Authority and New York police view the damage a day after a truck bomb exploded in the garage of the World Trade Center. (Richard Drew / Associated Press) More photos

He doesn't deny he once had influence. Of the Sept. 11 attacks, he said, "Maybe there was something I could have done, in my earlier life, to prevent such an occurrence."

Prison authorities initially suspected he may have had a role in Sept. 11, and Nosair was held in isolation for months. He remains in a special management confinement unit at a medium-security prison in Marion, Ill. He is appealing to the Bureau of Prisons to be put back with the general inmate population.

Nosair's first email arrived in late October. He complained that prosecutors overreached in the case against Sept. 11 mastermind Khalid Shaikh Mohammed as well as in his own case.

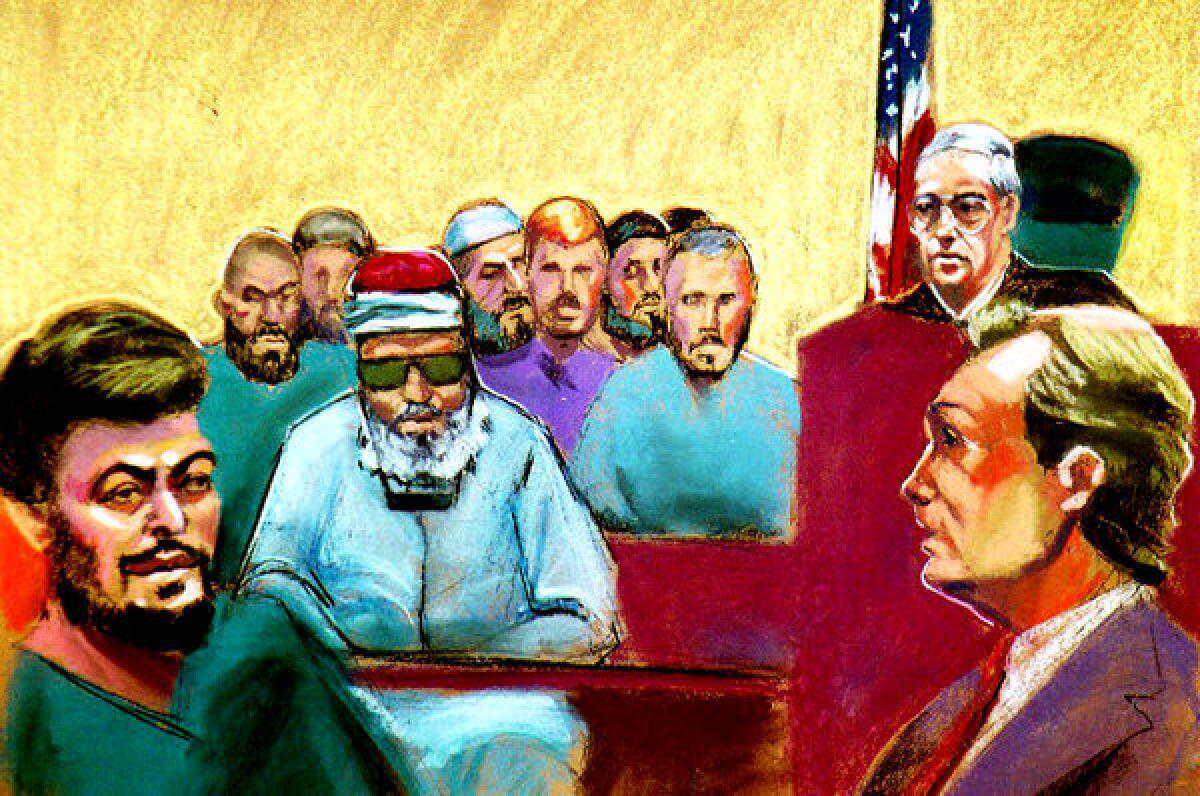

Nosair said he still idolized Omar Abdel Rahman, the blind sheik from Egypt convicted with him for plotting the 1993 World Trade Center attack. Rahman is serving a life sentence in a North Carolina prison. Although today he disagrees with Rahman's tactics, he still is inspired by his preaching from their days together at a New York-area mosque where Rahman urged Muslims to be strong.

"He understood to call the Muslims to stand up and fight for your rights," Nosair said. "He had done that in Egypt even though he faced prison. That's why I admire him."

Maybe there was something I could have done, in my earlier life, to prevent such an occurrence."— El Sayyid A. Nosair, speaking of the Sept. 11 attacks

Nosair immigrated to the U.S. from Egypt in 1981 and became a citizen. He worked as an engineer at the state courthouse in Manhattan and, while involved at two local mosques, became aware of Kahane. He also helped raise money, buy guns and recruit fighters to drive the Soviets out of Afghanistan.

On weekends he and others took up semiautomatic rifle training on Long Island; they collected detonators and wires. Soon, at the urging of the blind sheik, Nosair targeted Kahane.

"Everybody was under the spell of Rahman," said Jeanne King, a freelance writer once close to the Nosair family. "That's where the sheik got to him. He said, 'You've got to kill Kahane.'"

On the night of Nov. 5, 1990, Nosair shot the rabbi after Kahane called for American Jews to move to Israel before it was too late. He also wounded an elderly man and a postal detective, who in return shot Nosair in the neck.

A jury acquitted Nosair of murder in state court but convicted him on gun charges. The judge, who disagreed with the murder acquittal, sentenced Nosair to the maximum 22 years on the gun conviction.

Nosair was hailed a martyr by supporters carrying placards outside the courthouse. Many were followers of Osama bin Laden, who contributed $20,000 for Nosair's defense.

"He donated money just like any other Muslim did," Nosair said.

In state prison in Attica, N.Y., Nosair often was visited by old cohorts. "He was a star and a hero in the jihad," prosecutor McCarthy said.

Federal agents monitored the meetings, enlisted an informant and recorded bomb-making activities inside a safe house in Queens.

El Sayyid Nosair, left, Sheik Omar Abdel Rahman, center, and 13 codefendants appear at their arraignment in New York in Aug. 26, 1993. They faced charges of conspiring to bomb targets including the World Trade Center and planning assassinations and kidnappings. (Ruth Pollack / AFP/Getty Images) More photos

Prosecutors assembled a conspiracy case that included the first World Trade Center explosion that killed six people and injured more than 1,000 others, and federal charges for the Kahane murder. In October 1995, Nosair was convicted of all charges and was sentenced to life with no parole.

According to FBI records, he confessed in 2010, signing an affidavit that "when I shot Meir Kahane I considered myself to be a radical Muslim. During that time I viewed my actions as necessary."

If ever released, Nosair wrote, he wants to reconcile with his two sons, who have changed their names and moved at least 19 times over two decades to avoid their father's notoriety.

"He is my son, by birth," Nosair said of his oldest, Zak. "But he has disowned me and my way of life."

Zak Ebrahim, as he is known now, has no interest in reuniting with his father. Today he gives lectures promoting peace by drawing on his and his father's past.

Ebrahim has said he could not forget the first time he and his mother visited Nosair in prison, passing the "tall gray walls and fences and the armed guards" to find his father in an orange jumpsuit, sitting in a plastic chair deep inside Rikers Island.

"I was 7 years old when my father went to prison," Ebrahim said in a 2011 speech to the Lehigh Valley Peace Coalition in Pennsylvania. "Not a day goes by that I don't wish he had chosen a peaceful life with his family."

Nosair also is mindful of the lost years, and how much the world has changed since that night of his arrest for the Kahane murder.

"Amazingly," he wrote on Nov. 5, "today marks exactly 22 years since this incident happened. In 1990 I was a young Muslim activist. My whole desire was to bring peace to the Middle East."

Instead he is serving a life behind bars, often in special or solitary confinement, a life he said "where once you've done as much time as I have, you keep your sanity by clinging to your faith."

More great reads

Angelina Jolie's choice is clear to one who faced it

'Go destroy them,' artist says of his paintings

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.