550,000 homes in Southern California have the highest risk of fire damage, but they are not alone

The Del Rosa neighborhood lost 121 homes when the Old fire swept down from the mountains. (Video by Brian van der Brug / Los Angeles Times)

- Share via

On a cataclysmic fall day in 2003, David Mead stood on the roof of his house using a garden hose to fight off an undulating river of embers that floated down his street.

When he saw the battle was lost, he jumped off and escaped in the car he had left running, just in case.

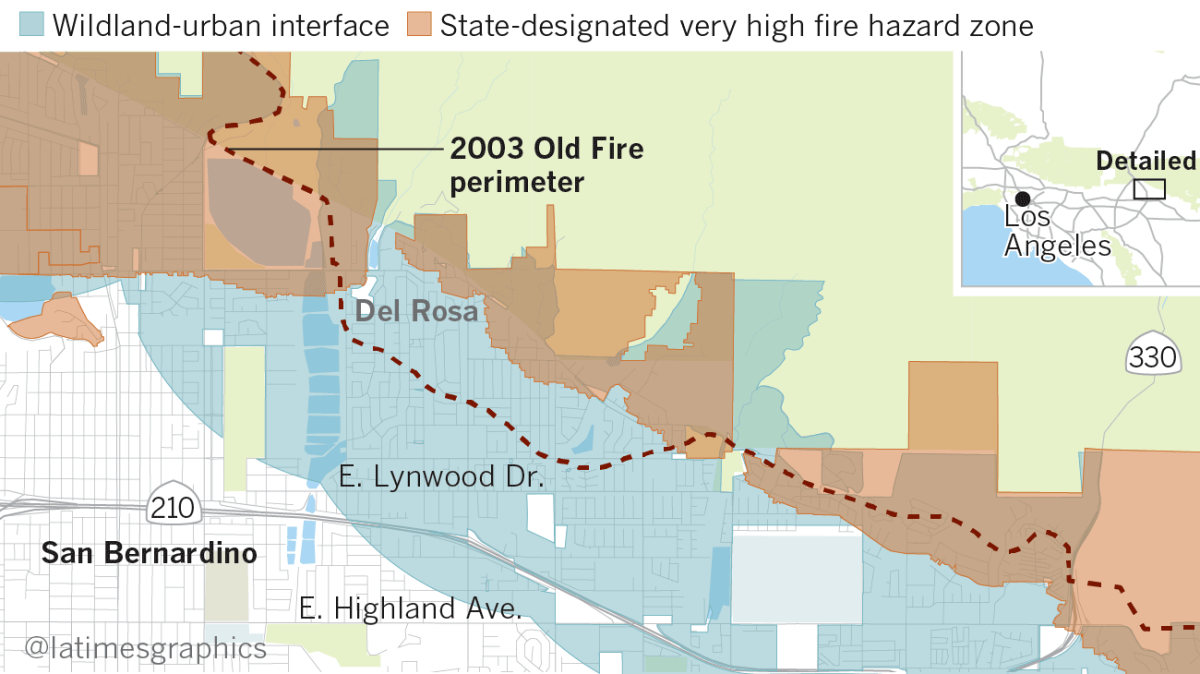

Mead’s house was one of 121 destroyed in the Del Rosa neighborhood of San Bernardino when the Old fire swept out of the mountains that day.

The decimation of that 1950s tract development at the foot of the San Bernardino Mountains illustrates a phenomenon that is commonplace in Southern California — neighborhoods built so close to forest and chaparral that they could fall to the kind of urban conflagration that wiped out a whole neighborhood of Santa Rosa in last month’s fires.

From Ventura to San Diego, hundreds of thousands of homes — both in mountain enclaves and flatland tracts — are part of what is called the wildland/urban interface, where there is a higher risk of fire. That’s because homes are close enough to wild land areas that ember from brush fires could spread to them.

For two decades state fire officials have been working to identify those vulnerable neighborhoods and tighten their defenses with fire-conscious building codes for new houses.

At least 550,000 homes vulnerable

But these programs leave existing homes more vulnerable to fires. A Times analysis of the state’s maps for the highest-risk fire areas in Southern California shows about 550,000 residences covered by the zones. If areas with a lower but still significant fire risk were added, the number would roughly double, The Times analysis found.

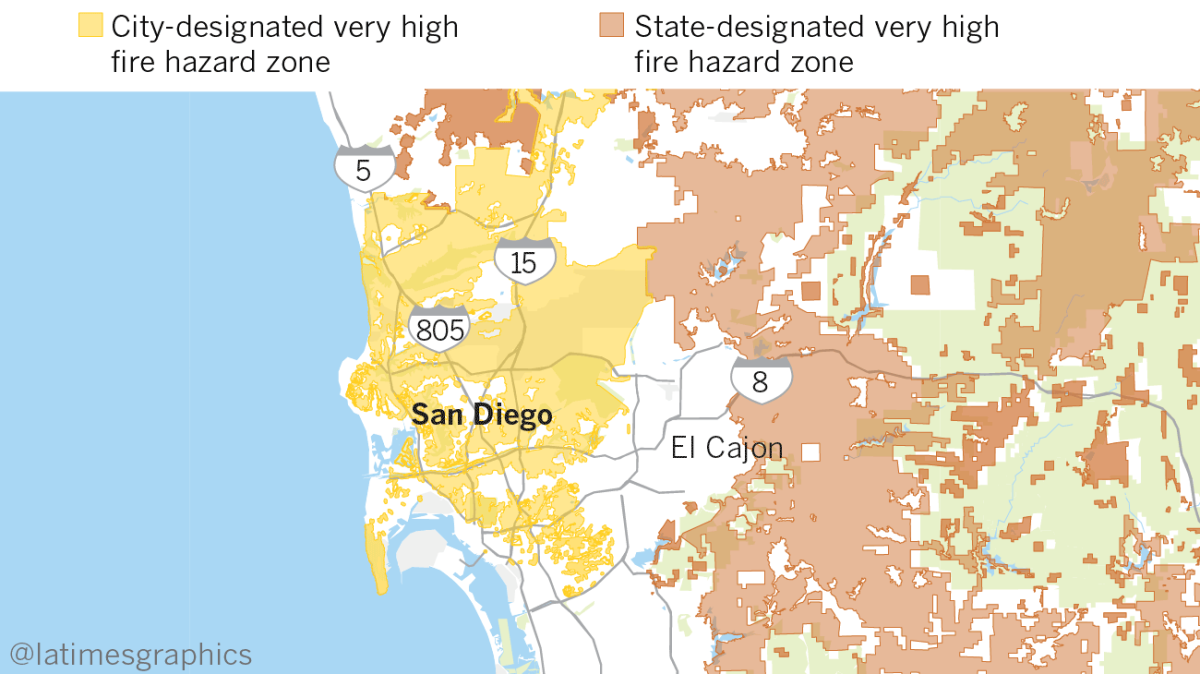

Complicating the situation, some cities such as Los Angeles and San Diego have expanded the state’s fire zones to include many more homes, while others have not.

Agoura Hills, La Canada Flintridge and four cities of the Palos Verdes Peninsula declared their entire areas hazard zones, said J. Lopez, assistant chief for the

San Bernardino County adopted the state boundary unchanged, despite an obvious flaw. The boundary excludes a portion of the Del Rosa neighborhood that burned in 2003. Replacement houses like Mead’s, built to more modern fire standards, are still outnumbered by ‘50s tract homes with features such as wooden siding and open eaves that would not be allowed today.

Only a short distance to the west, another neighborhood of about the same age is entirely inside the zone, even though it withstood both the Old fire and the Panorama fire of 1980.

The flaws in the mapping program reflect a conundrum officials face in modeling fire behavior.

Unlike floods, which flow in predictable plains, fires behave more randomly, especially in the relatively rare instances when wind-blown embers move outside the wild land edge into residential areas.

“When you have wind and embers, that’s super hard to map … that’s a big gap in our knowledge about how to identify the risk in a more practical way,” said Michele Steinberg, wildfire division manager at the National Fire Protection Assn.

Hazard maps attempt to define a wildland/urban interface using algorithms that take into account vegetation, topography and wind speed.

In urban Southern California, small differences in where the lines are drawn can cause big swings in the numbers affected.

The Times analysis found that about 450,000 housing units currently mapped outside the zone would be included if the state used the wildland/urban interface boundary mapped by a Wisconsin research lab called Silvis.

The benefits from including so wide an area are also hard to calculate. Statistically, it is highly unlikely that any given neighborhood will become the next Santa Rosa.

The destructive fire cycle

But the more than 100-year record of Southern California wildfires shows that some will, resulting in huge losses.

In 1961 a fire that began in a trash heap and was propelled by gusting Santa Ana winds destroyed nearly 500 homes in Bel-Air and Brentwood — including those of Hollywood stars such as Zsa Zsa Gabor and Burt Lancaster.

Less than 10 years later, in 1970, more than 400 homes in Agoura Hills, Chatsworth and Malibu were lost in a blaze that burned in a wall from Newhall to the ocean.

More recently, the Cedar fire in 2003 and Witch and Harris fires in 2007 destroyed about 3,500 homes in total across San Diego County.

Not all of those houses were in flatland tract developments like Del Rosa. But a post-mortem of the 2007 Grass Valley fire in Lake Arrowhead concluded that the mountain neighborhood burned from home to home in a pattern characteristic of a residential fire.

“Home ignitions did not result from high intensity fire spread through vegetation that engulfed homes,” scientists wrote in a 2008 report to the U.S. Forest Service. “The home ignitions primarily occurred … due to surface fire contacting the home, firebrands accumulating on the home, or an adjacent burning structure.”

In trying to strike a balance between defining hazard either too narrowly or too broadly, state law currently wavers between two standards. Areas that fall under state jurisdiction, including most rural areas, are classified in three tiers — moderate, high and very high hazard. Structures in all three zones are subject to stricter building codes.

But laws dating to the 1990s provide a less inclusive standard for areas designated local responsibility, primarily cities and urban counties. The state’s recommended maps show only areas where the hazard is designated as “very high” severity.

Very high severity zones generally stop a short distance from mountain’s edge, even though fires do not.

Flanked by both the San Gabriel and Verdugo mountains, central La Canada Flintridge became what Robert Stanley, director of community development, called a “doughnut hole” in the fire zone.

The city’s solution, Stanley said, was partly motivated by fairness.

“It didn’t make sense to try to delineate who would have to comply with the fire codes or not,” Stanley said. “They said just do the whole city.”

It was also influenced by lessons of the fire that destroyed nearly 2,900 homes in Berkeley.

“In a wind-driven fire it’s not going to stop at that zone,” Stanley said. “It’s going to drive right through.”

San Diego’s modifications were influenced by the devastation of the Cedar fire. When Cal Fire issued its recommended zone, San Diego found that the state had missed some areas, according to reports to the City Council at the time.

“Cal Fire’s used to dealing with big, huge forested areas, but in our city there’s a lot of finger canyons … that become a risk,” said San Diego Fire-Rescue Department Assistant Fire Marshal Eddie Villavicencio, who was a code enforcement officer at the time.

The map that the city ultimately adopted, in 2009, added dozens of those finger-like extensions, plus a wide swath of central San Diego that included the community of Scripps Ranch, a neighborhood of medium to large tract homes that burned down in the Cedar fire.

Before the 2003 and 2007 fires, Villavicencio said, “People were just thinking only the houses on a canyon rim needed to be hardened or needed defensible space.”

“When you have these types of catastrophic disasters, you’re going to have this deluge of embers carried half a mile or a mile away,” he said.

Making homes safer — at a price

New homes built in designated fire hazard severity zones must be built according to regulations laid out in Chapter 7A of California’s building code.

These include using non-combustible materials for roofs and wall sidings and eaves, attic vents that prevent embers from entering houses and double-pane, tempered glass windows.

Homeowners must also maintain a brush clearance zone within 100 feet of their property.

Even in neighborhoods demarcated as high severity hazard zones, building standards apply only to new construction.

Though retrofitting has been mandated for some hazards, such as a Los Angeles ordinance requiring seismic strengthening of some buildings, there has been no push so far, either at the state or local level, to require existing houses in fire zones to be upgraded.

Some critics of current fire prevention practices argue that spending money to harden communities would be more effective than the current focus on controlling flammable growth in the wild land.

“In terms of community protection, you want to start from the house out,” said Richard Halsey, director of California Chaparral Institute. “Putting the money there is so much more efficient than maintaining fuel breaks and grinding up vegetation and doing prescribed burns. And it’s a one-time deal.”

But mandatory retrofitting programs would be difficult to implement because of the vague harm associated with living in an area where a natural disaster might or might not occur, said Steinberg of the National Fire Protection Assn.

Researchers, in fact, still don’t have a firm understanding of how much upgrades cost and how to weigh the cost against the benefit.

“It requires some assumptions,” said Stephen Quarles, a fire scientist with the Insurance Institute for Business & Home Safety.

A house with no close neighbors could be made safer without great expense by installing proper screens on attic vents, Quarles said.

But, he said, “If your neighbor is 10 feet away, the cost would be greater but the benefit would be greater.”

Insurance companies can offer incentives, too, such as providing discounts to those who do retrofit or refusing to insure those who lack protections.

Steinberg said that, unlike for disasters like earthquakes or floods, many of the fire retrofits do not require “engineering solutions,” such as elevating a home or reinforcing the foundation. Many are steps homeowners would take in the course of owning a home, such as replacing a roof or clearing out the rain gutters.

Although the benefits may be slow coming when building codes apply only to new construction, the effect can be substantial over time.

A fire department report after the Bel-Air fire identified wood-shingle roofs as a leading cause of the fire’s widespread damage to homes and the difficulty in controlling it.

Through public education as well as prohibitions in some areas, wood-shingle roofs have become rare, especially in fire-prone areas.

Fire departments in some jurisdictions ask home builders to do more than state law requires.

Nearly 10 years ago, Greg and Dana Carlson custom-built a house on a stunning plot of land in Cowan Heights, backing up to a wild area that has burned repeatedly in what is now a very high severity hazard zone.

Nick Pivaroff, Orange County Fire Authority assistant fire marshal, said his department worked closely with the Carlsons to ensure the house would be fire resistant.

The sprawling ranch-style property features metal roofing, stucco walls, and oversized timber pillars, sprinklers in the covered backyard and fire-resistant landscaping. There is even an access path for firetrucks.

“It was one big check after another,” Dana Carlson said of the construction process. “I think it was $30,000 just for the gravel” in the driveway, she said.

When the Carlsons asked for a shortened fuel modification zone, Pivaroff pushed back. The Carlsons said they ended up having to obtain an easement from neighboring Peters Canyon Regional Park to have permission to clear vegetation in what was essentially their backyard.

“We knew it was a historical corridor,” Pivaroff explained, referring to the 1967 Paseo Grande and 2007 Santiago fires. “We knew it was going to happen again.”

Earlier this month Pivaroff’s prediction became reality. When the Canyon Fire 2 tore through northeastern Orange County, it stopped precisely at the fire break the Carlsons had drawn. Firefighters used the access route and even relied on two fire hoses the Carlsons had connected to their pool.

A week later charred hills could be seen from their backyard and red remnants of flame retardant still spattered the roof, but the house had been untouched.

“I talked to him the day after, and all he could say was ‘thank you,’” Pivaroff said of Greg Carlson.

ALSO

PG&E says private power line might have sparked deadly wine country fire

Warning sirens stayed silent the night deadly wildfires swept into Mendocino County

Mudslide fears haunt neighborhoods burned by huge La Tuna fire

Santa Rosa residents warned of possible sinkholes and landslides in burn areas amid upcoming rain

UPDATES:

FOR THE RECORD

Nov. 13, 8:20 a.m.: An earlier version of this article referred to the San Gabriel Mountains. The reference should have been to the San Bernardino Mountains.

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.