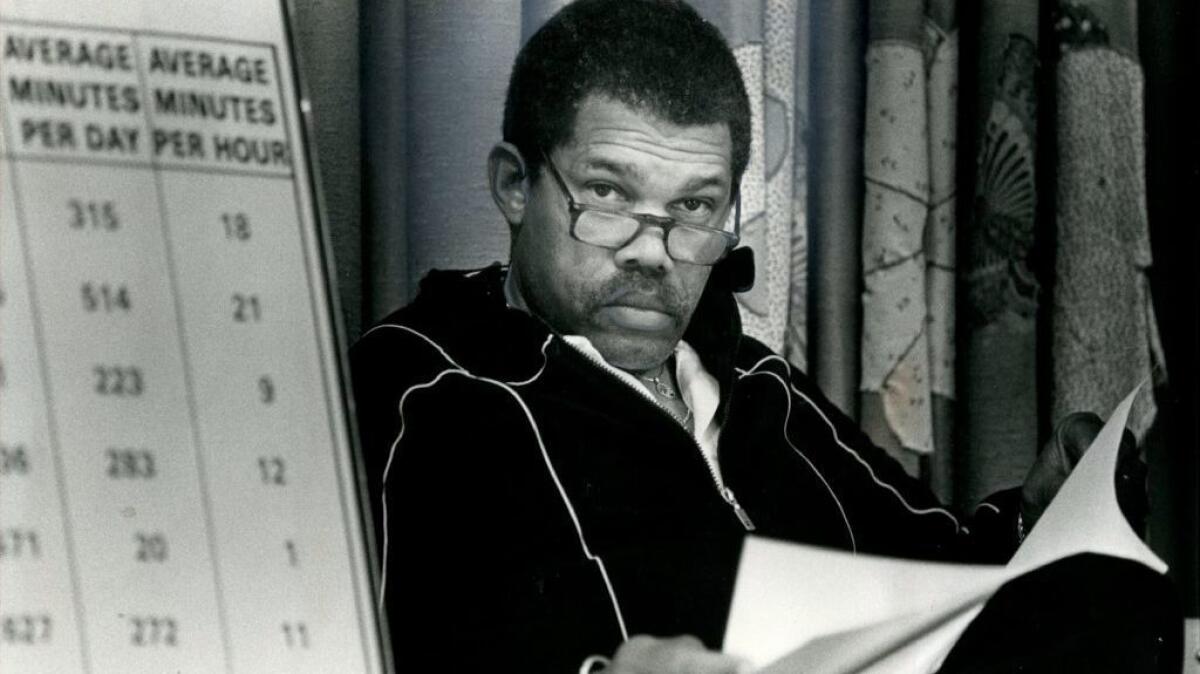

David Cunningham Jr., former L.A. City Councilman, dies at 82

- Share via

David Cunningham Jr., who succeeded Tom Bradley on the Los Angeles City Council in 1973 and emerged as a forceful voice at City Hall for African Americans, has died.

Cunningham, 82, died Wednesday at Kaiser Permanente West Los Angeles Medical Center following a battle with cancer, said his son David Cunningham III.

Cunningham, who served on the council until 1986, was a pro-business politician who championed social justice and civil rights issues. He pushed for new affordable housing, led a campaign for the city to divest its holdings in apartheid-era South Africa, and encouraged the hiring of minorities and women.

His tenure on the council was one chapter of a colorful career that included working in Nigeria, running a consulting company and appearing in a Chris Rock movie. An avid jazz musician who played bass in a band, Cunningham was a “man for all seasons,” his son said.

He was born June 24, 1935, in Chicago. His father, David S. Cunningham Sr., a Christian Methodist Episcopal Pastor, was a leader in the civil rights movement.

He attended the 1960 Democratic National Convention in Los Angeles, where he caught the political bug after hearing John Kennedy’s acceptance speech and moved to the city shortly afterward, his son said.

Cunningham earned a bachelor’s degree in political science and economics from UC Riverside and a master’s degree in urban planning from Occidental College. He worked briefly for Democratic Assemblyman Charles Warren, then entered the private sector, working as the West African regional manager for an electronics company and helped run a consulting firm in Los Angeles.

At the urging of friends, he launched a successful campaign for the council seat opened up by Bradley’s historic election as L.A.’s first black mayor. Cunningham faced a field of challengers that included ‘Star Trek” actor George Takei.

Bradley endorsed Cunningham, and would remain his close ally.

Overseeing a district that included Pico-Union, Koreatown, Fairfax and West Adams, Cunningham pushed for funding for low- and moderate-income housing and created the 10th District Women’s Steering Committee, which is still active.

As chairman of a committee focused on housing and community development, Cunningham called on federal housing officials to put thousands of boarded-up homes owned by the government back into use.

He also used his committee role to encourage minority hiring at investment banks that sought work with the city. When Cunningham traveled to New York to meet with bank executives, “he would tell them, ‘I don’t see anyone working for you that looks like me,’ ” said Gregg Irish, a family friend.

Cunningham opposed a citywide push for rent control, believing it would be an impediment to the construction of affordable housing.

The 6-foot-3 Cunningham was affable and had an easygoing manner. But friends and family members said that on issues he cared deeply about, his temper could flare. He once nearly came to blows in the council chambers with fellow Councilman Art Snyder.

In the early 1980s, he was a key ally in Councilman Zev Yaroslavsky’s crusade to shut down the Los Angeles Police Department’s infamous Public Disorder Intelligence Division, which kept files on civil rights organizations and other activist and civic groups.

Cunningham knew how to sway his colleagues on issues, but was always forthright on his own position, Yaroslavsky said.

“When he gave you his word, he was rock solid,” Yaroslavsky said. “And when he wasn’t with you on an issue, he’d tell you so.”

According to Irish, Cunningham’s wide circle of friends included Ernie Green, one of the members of Little Rock Nine. The group integrated a Little Rock, Ark., high school in 1957, a key step in the civil rights movement.

As a councilman, Cunningham hired John Carlos, a U.S. track star who raised a black-gloved fist on the medal stand at the 1968 Mexico City Olympics.

Ostracized because of his protest, Carlos couldn’t find work, so Cunningham hired him as an aide.

“David thought that wasn’t right and everyone should get a job,” Irish said.

Cunningham unexpectedly stepped down from the council in 1986 and took a job at Cranston Securities, an investment banking firm.

In his resignation letter to the council, he wrote that “someone once said it is better to leave too soon than to stay too late, but I truly believe it is better to leave beloved as opposed to belated.”

In the early 1990s he joined an acting troupe. That led to appearances in the movie “CB4” with Rock and Ice Cube, and the NBC sitcom “227.”

Married three times, Cunningham is survived by his wife, Sylvia, and six children: David, Leslie, Robyn, Amber, Sean and Brian.

Funeral services are planned at First African Methodist Episcopal Church of Los Angeles on Monday at 10 a.m.

Twitter: @dakotacdsmith

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.