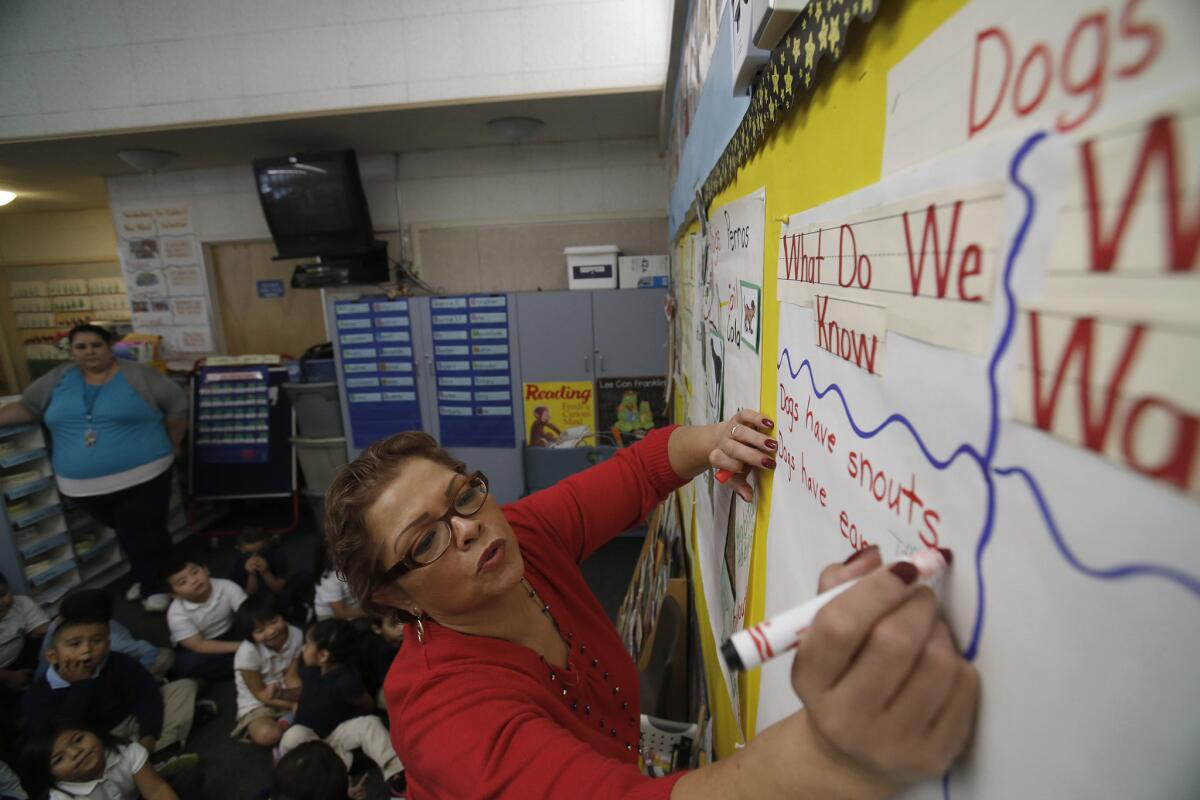

U.S. officials step up efforts to help students learning English

- Share via

Concerned that too many public schools are failing to adequately help students learning English, federal officials Wednesday unveiled guidelines on the legal requirements to identify and support them.

The U.S. Departments of Justice and Education, which jointly issued the guidelines, have increased their enforcement of laws passed more than four decades ago that require such services amid growing numbers of students who are struggling with English. Nationwide, such students number about 5 million – about 9% of all public school pupils – and they have increased in most states between 2002 and 2012.

At the same time, the Department of Education’s civil rights division has received more than 475 complaints alleging substandard services for students learning English and is actively conducting 60 reviews in 26 states. That includes 100 complaints and four reviews in California.

“It really feels like the need is mushrooming,” said Catherine E. Lhamon, the Department of Education’s assistant secretary for civil rights. “We are seeing serious compliance concerns around the country so we felt it was time to issue the guidance.”

But Lhamon said she was “pleased at the progress” in the Los Angeles Unified School District, which has overhauled its services for students under a 2011 agreement with the Department of Education. The district has added new courses, teacher training and other improvements. Since 2009, 22 other school systems have also forged agreements with the civil rights office to increase services, including Long Beach, San Diego, Pasadena and Oakland.

In addition, California legislators have revamped the state’s school finance system to earmark more money for students learning English. They also recently stepped up efforts to identify and help students who fail to become proficient in English even after seven years in California classrooms.

“California is obviously a state that is very, very important on this front,” Lhamon said.

The 40-page guidance reminds states and school districts that federal laws require them to identify students who need English support, offer them high-quality assistance by qualified staff, provide equal access to school programs and activities, avoid unnecessary segregation from mainstream students, move them out of support programs when they are fluent in English, evaluate the effectiveness of the programs and move students out of them when they become fluent in English and provide parents information in languages they can understand.

Title VI of the Civil Rights Act of 1964 bars schools receiving federal funds from discriminating on the basis of race, color or national origin. In a seminal 1974 case, Lau vs. Nichols, the U.S. Supreme Court held that failing to provide services for students learning English violated that law; Congress subsequently passed the Equal Educational Opportunities Act of 1974 requiring public schools to take “appropriate action” to help students overcome barriers to English fluency and ensure their equal access to school programs.

“All children deserve the opportunity to succeed in school, no matter where they are from or what language they speak,” said Vanita Gupta, the U.S. Dept of Justice’s acting assistant attorney general for civil rights.

Twitter: @TeresaWatanabe

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.