Robert Schuller’s California brand of Christianity

- Share via

On a bright Sunday morning in the spring of 1955, Robert Schuller saw the future.

Standing behind the altar that he had built and near the cross that he had raised, he looked out over a crowded parking lot and knew that he was not alone in his dream.

A drive-in theater as his church, his congregants comfortable in their cars, he opened with Matthew 19:26 — “with God all things are possible” — and set a course that in the coming decades would draw millions of followers.

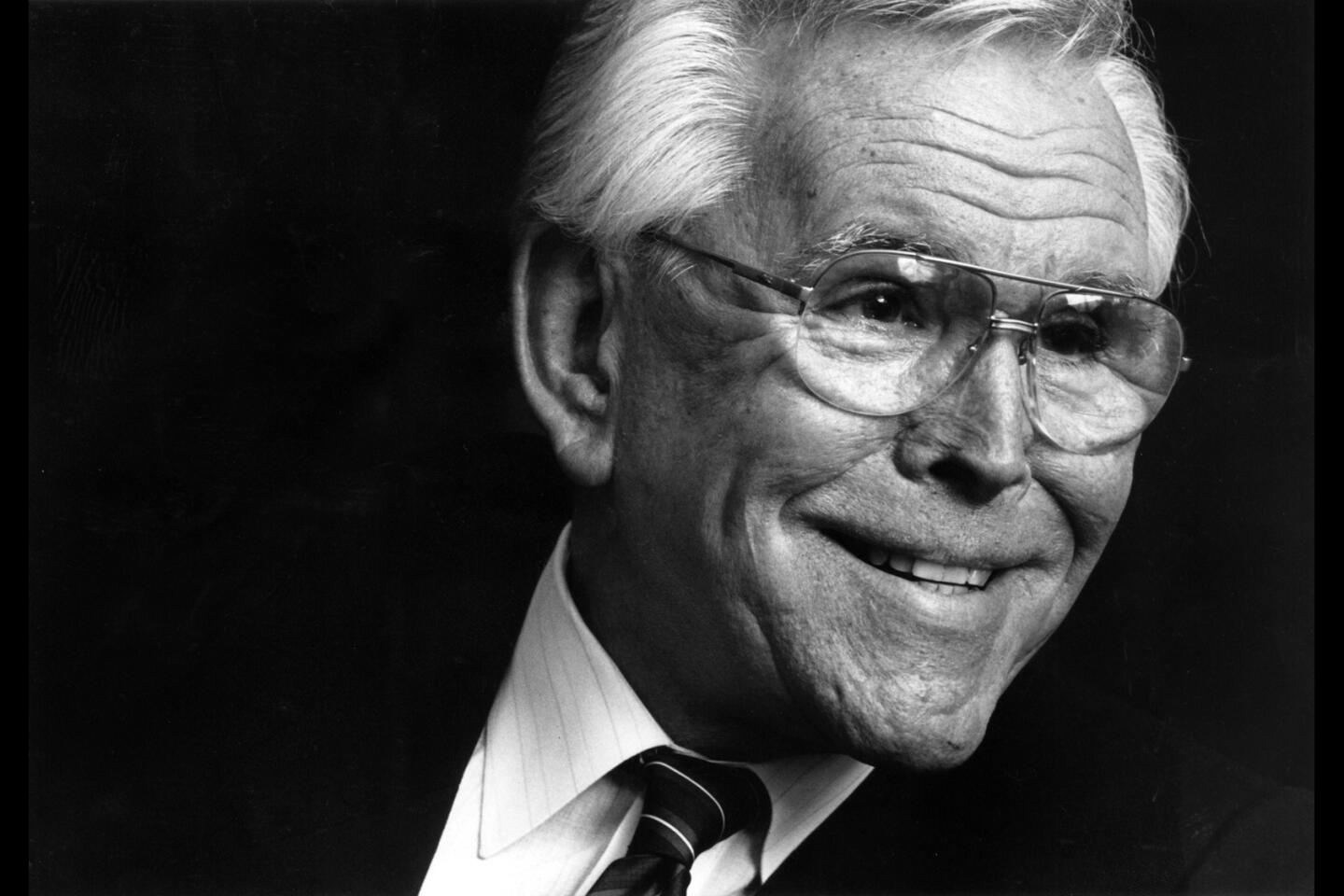

Schuller, who was diagnosed with esophageal cancer in 2013, died Thursday morning at a skilled nursing facility in Artesia, his daughter Carol Milner said.

His weekly sermons, eventually televised to more than 150 countries and tailored into a series of best-selling books, turned the strictures of Christian faith into an endorsement of hope and possibility.

If the message — what would become his “theology of self-esteem” — had an air of relativism, it hardly mattered. It was first delivered at a time when the Cold War, McCarthyism and the Bomb had hardened the nation’s conscience.

His message might have been lost, even dismissed, had it not become so popular, drawing hundreds, then thousands to his drive-in church. Orange County was hardly a wilderness, but in the symmetry of its streets, Schuller found a home “burgeoning, untamed and very secular.”

But Southern California has always welcomed new faiths. Celebrity evangelists like Amy Semple McPherson, broadcasters like Charles Fuller, theosophists and occultists alike discovered an audience here.

What they shared was an ability to tap into, even exploit, the spirit of the time.

Schuller tailored his message to a congregation that was unburdened by the past and unwilling to be judged by others. Transplants like him, most had escaped the East, rejected the harsher pronouncements of traditional religions and found promise in prosperity and reinvention.

Driving new cars, working new jobs and going home to their new suburbs, they could spend an hour in his company and feel that they had enjoined a more timeless set of beliefs and values.

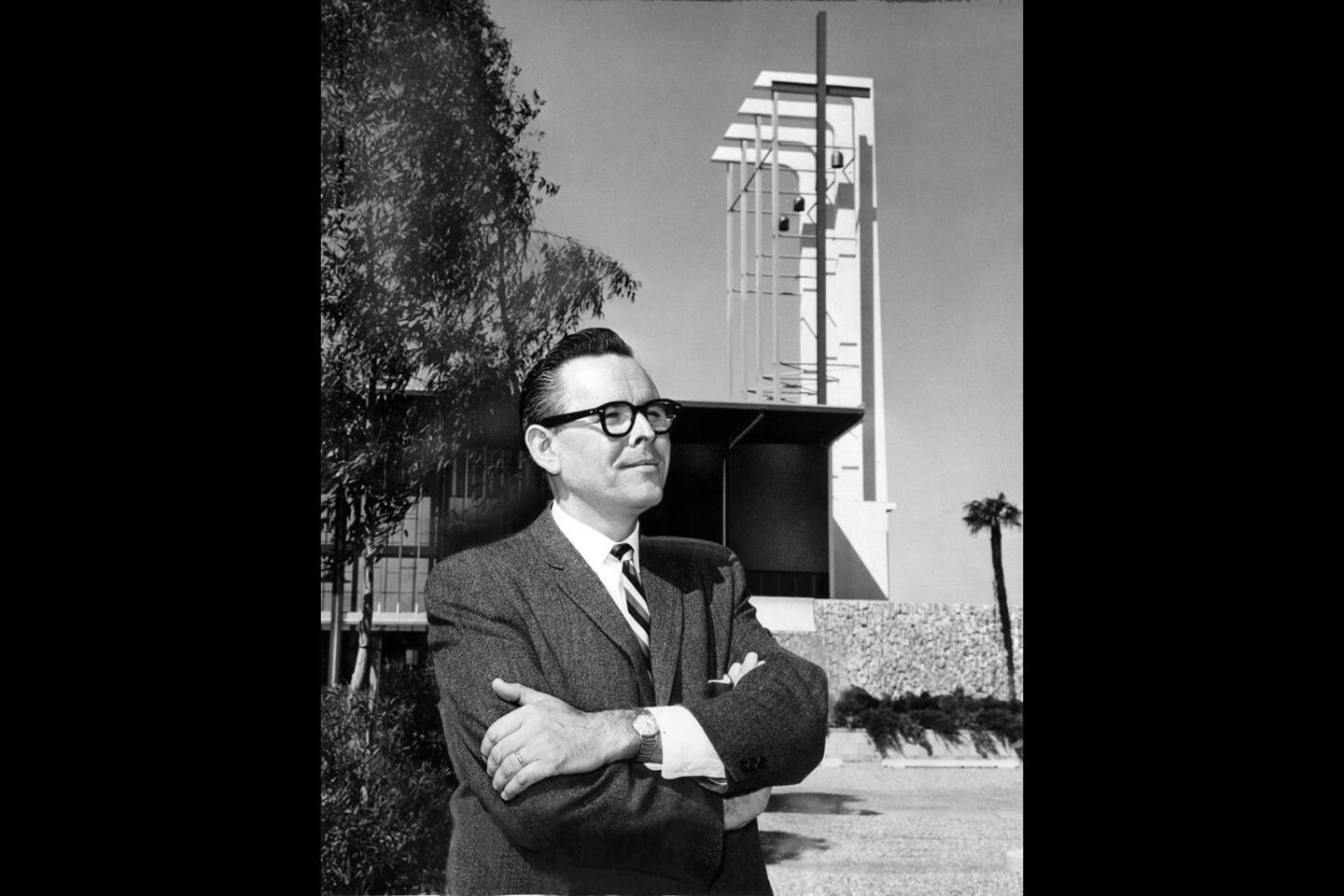

Schuller first caught a glimpse of the Golden State in the late 1940s. The mountains and palm trees of Los Angeles were enticing, but after a trip to the beach, dressed in his suit and tie, he was filled with an “unchangeable compulsion to live in California.”

Nearly a decade later, he loaded up his ’53 Chevy, and with his wife and two young children left Chicago for Garden Grove. He had $500 and an electric organ. He just needed a pulpit.

He didn’t take credit for the idea of a drive-in church. For that, he cited a Methodist minister from Florida who delivered equally upbeat messages to parishioners in their cars.

Let other churches ridicule the gimmick. Schuller found familiarity in these open spaces. His drive-in and his churches celebrated the outdoors and redefined what a sacred space could be.

“I fell in love with the sky,” he once said. “Growing up in Iowa, I watched the clouds sliding silently through that soundless sea of space.”

He said that he wanted to put “strong wings on weary hearts,” and like many preachers, he was shrewd enough to know that his success depended upon his ability to understand his congregation’s capacity for guilt.

As he once observed, unchurched people are kept out of church by a sense of guilt, “the same way an overweight man avoids stepping on a bathroom scale.”

So Schuller also made sure that their encounter with God left them unscathed. Turning “stress into strength” was not only his message; it was also his experience.

Climbing the wooden ladder to the top of the concession stand, as he did every Sunday for six years, he felt the sticky tar paper under his feet. He smelled Saturday night’s popcorn still in the air, and he filled the collection plate.

At the end of his first service, he collected almost $90 in donations.

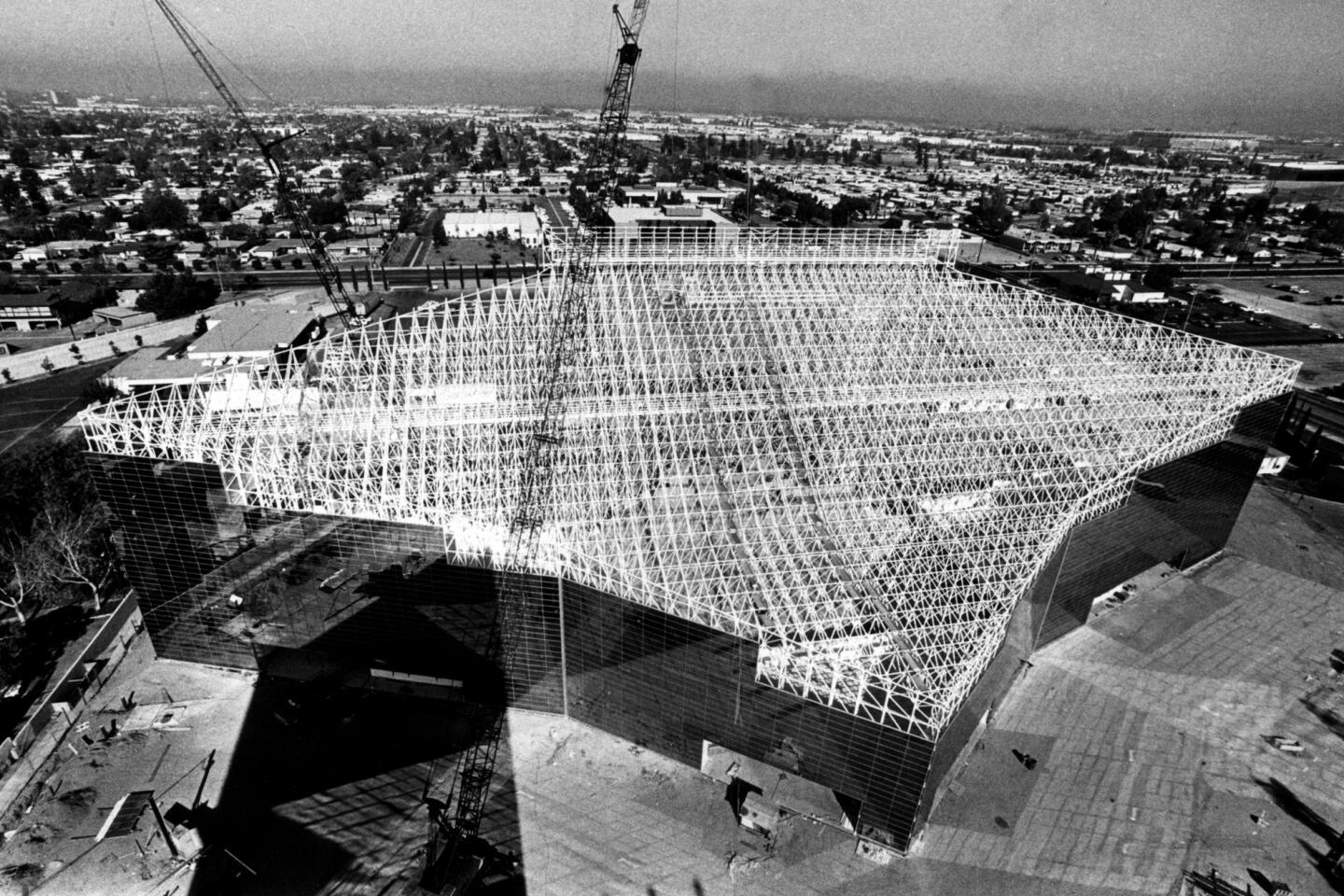

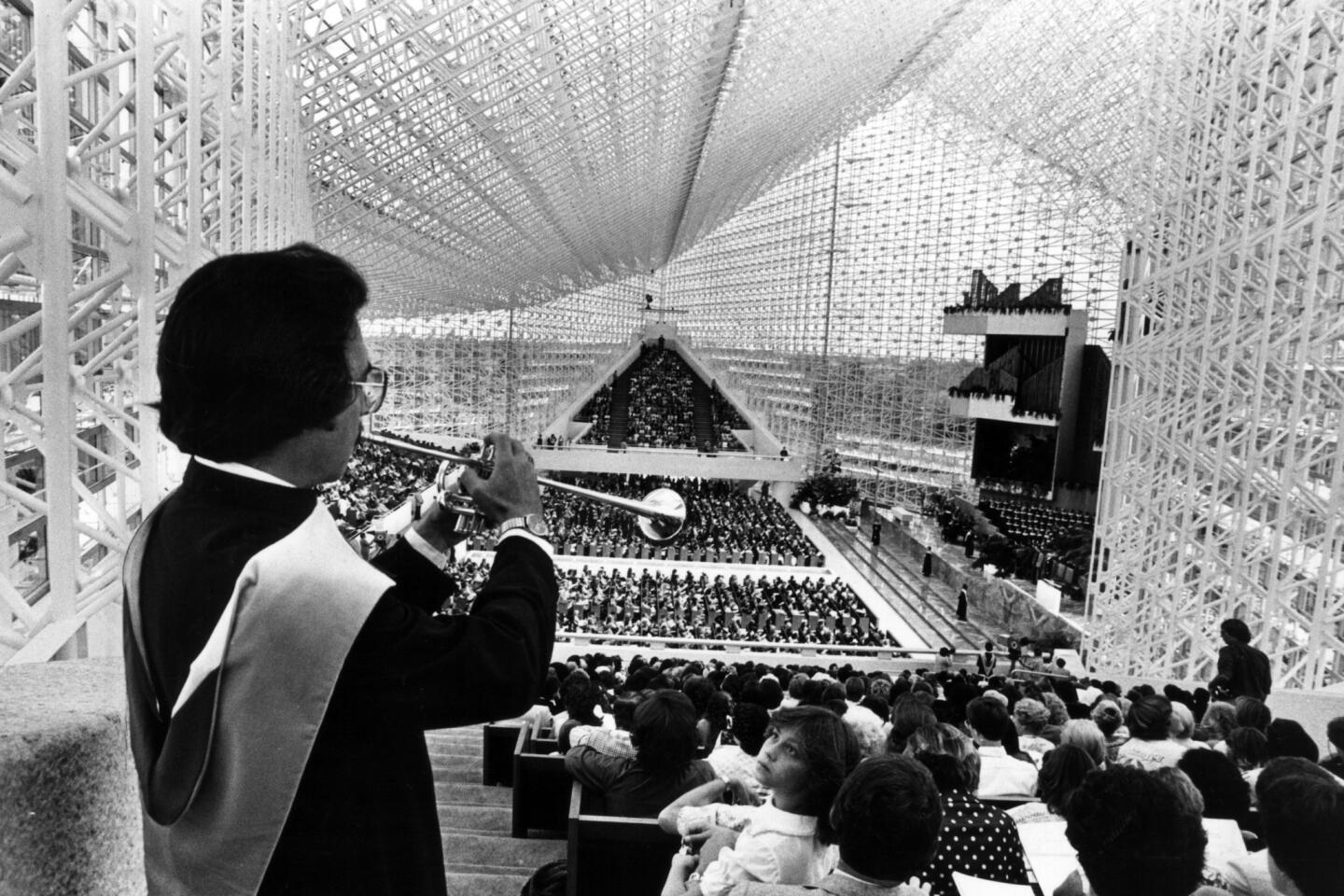

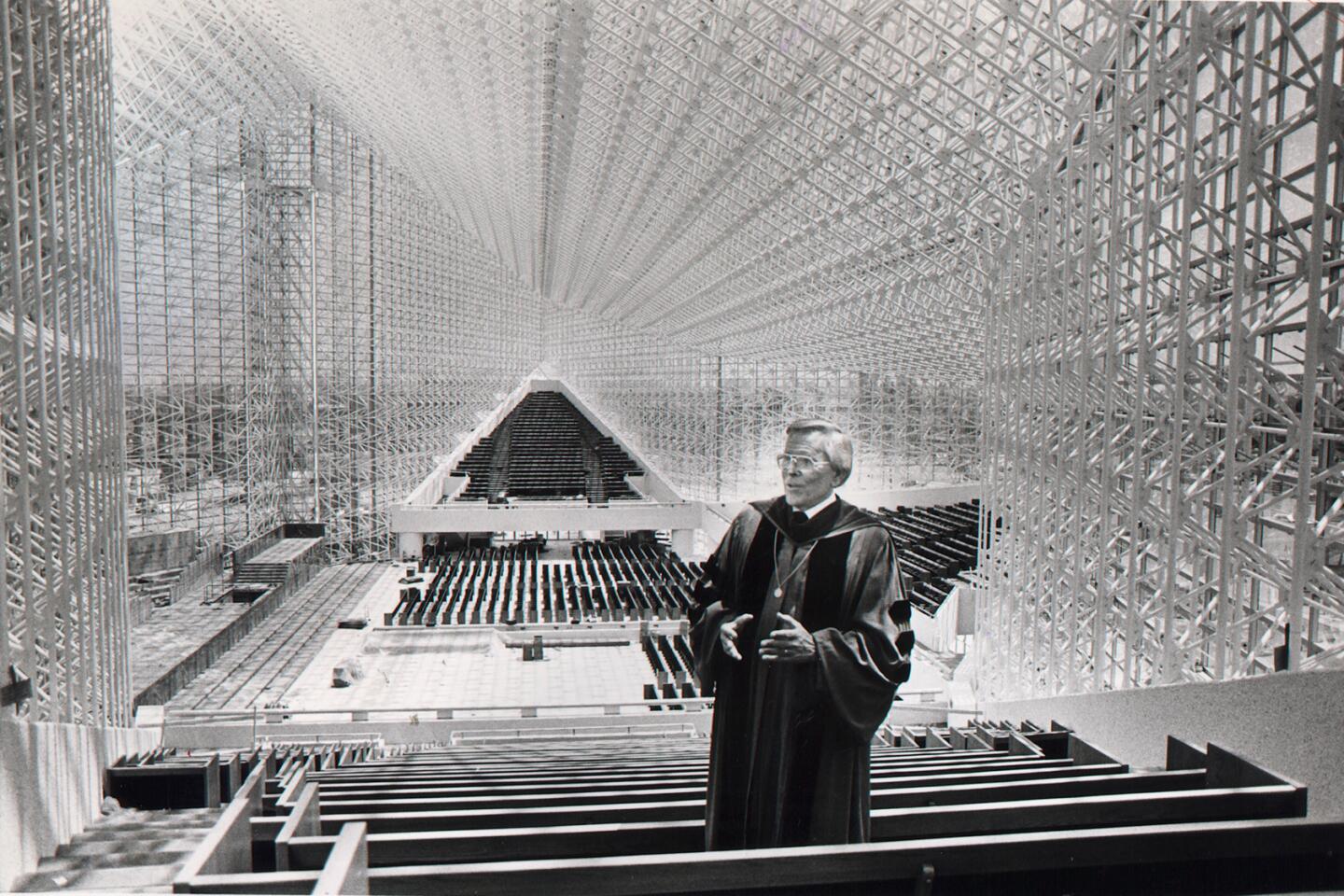

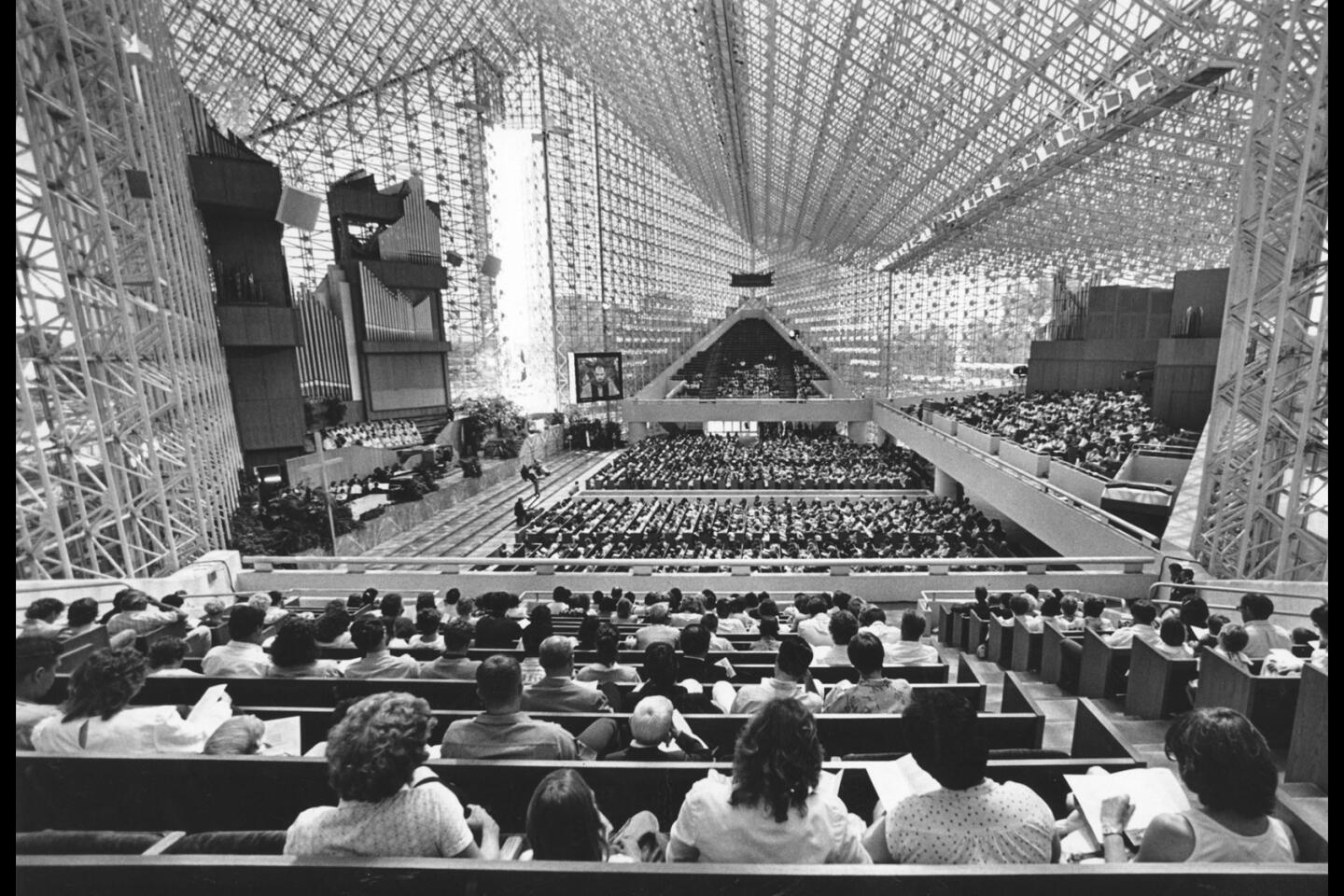

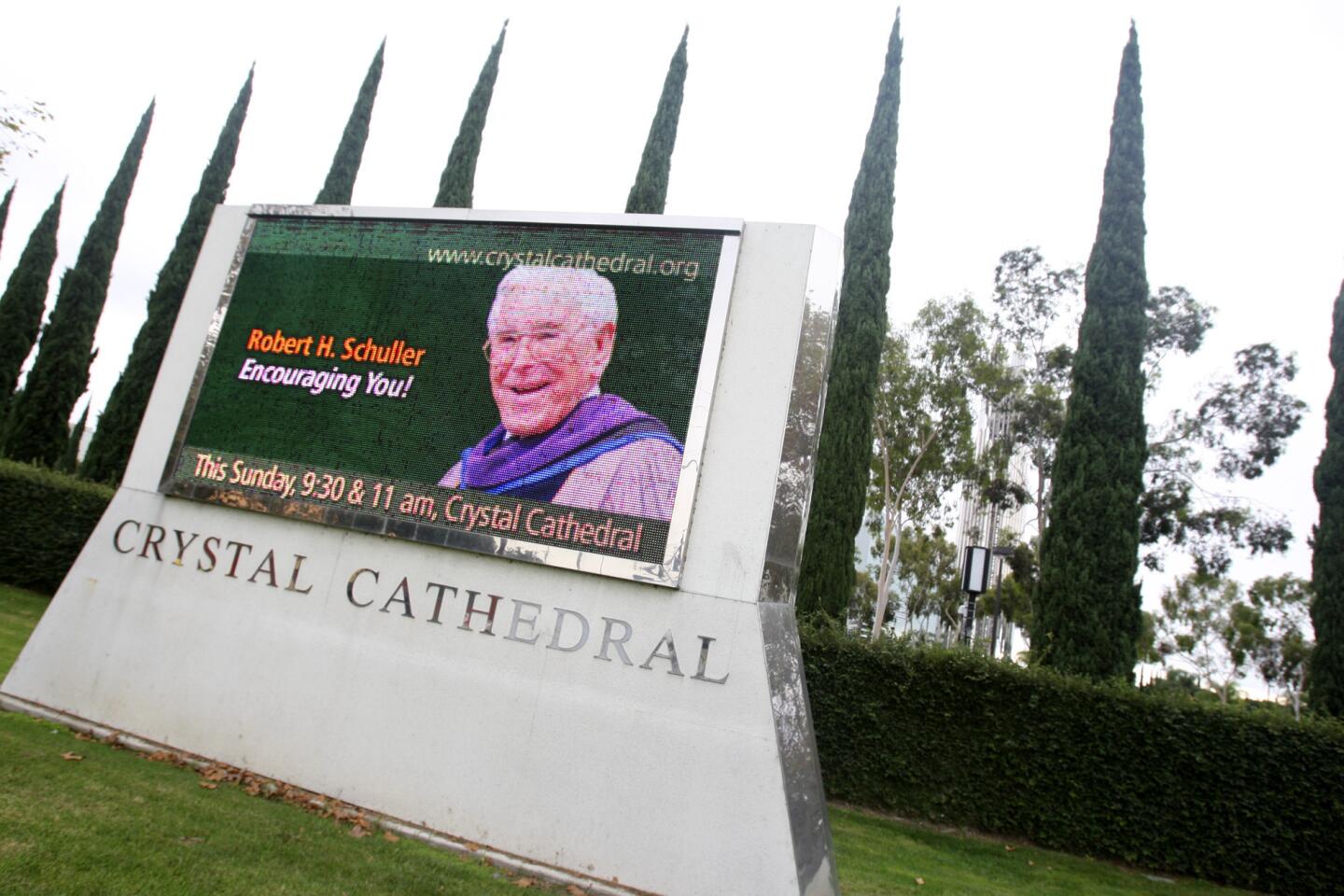

Almost 25 years later, he claimed to have made $1.4 million on a Sunday that had wheelbarrows and buckets as his collection plates in an effort to offset cost overruns during the construction of the Crystal Cathedral.

Horatio Alger could not have told a better rags-to-riches story, and often the stories that Schuller shared sounded too mythic, too perfect to be true. But that was the measure of the man: He never met an obstacle he didn’t like.

He was, above all, a retailer of his religion. From advertisements in local papers with their tag line — “Come as you are … in the family car” — to an initial mailing list of 3,500 compiled after going door to door, he sold his message. His first church he once described as a “22-acre shopping center for Jesus Christ.”

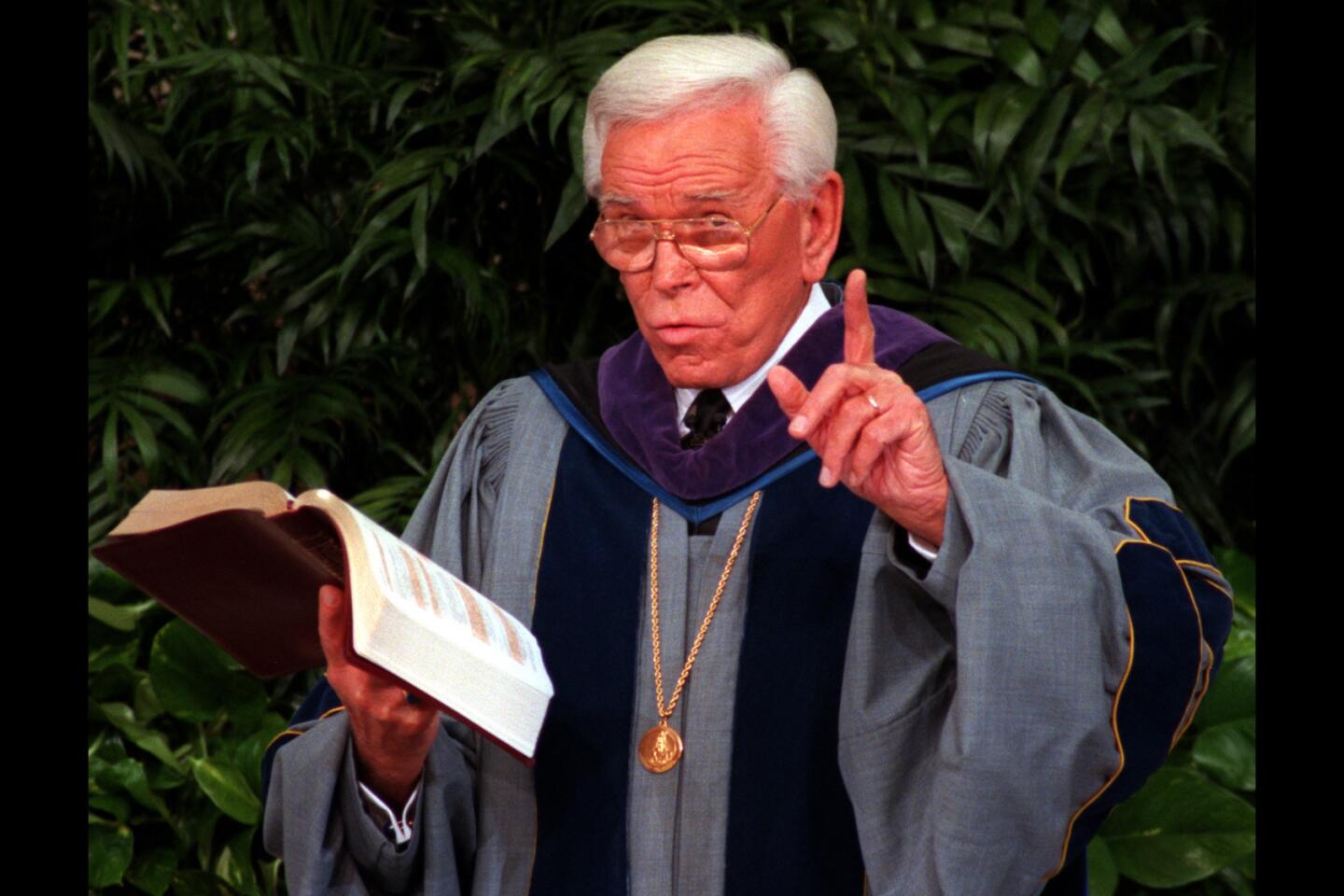

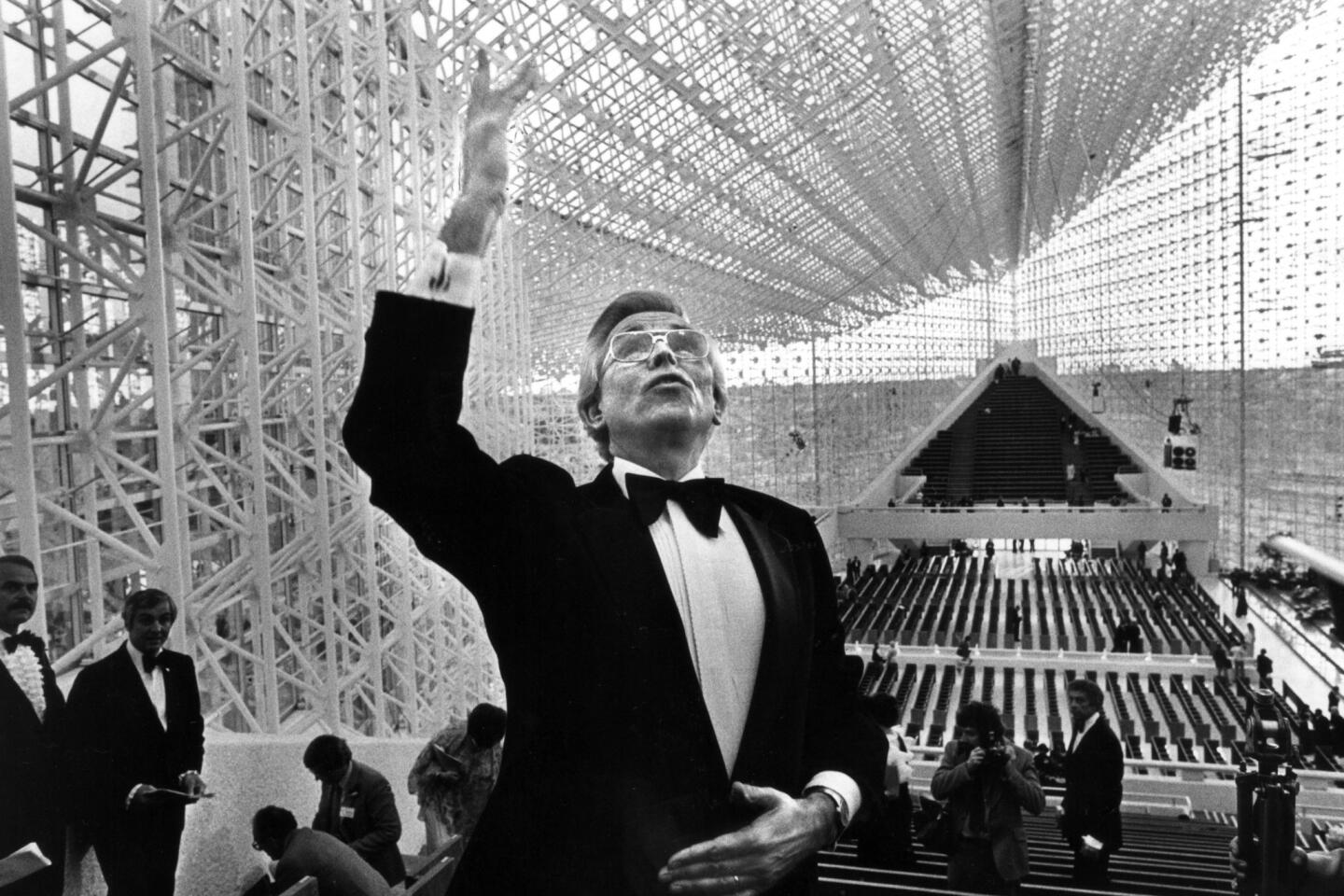

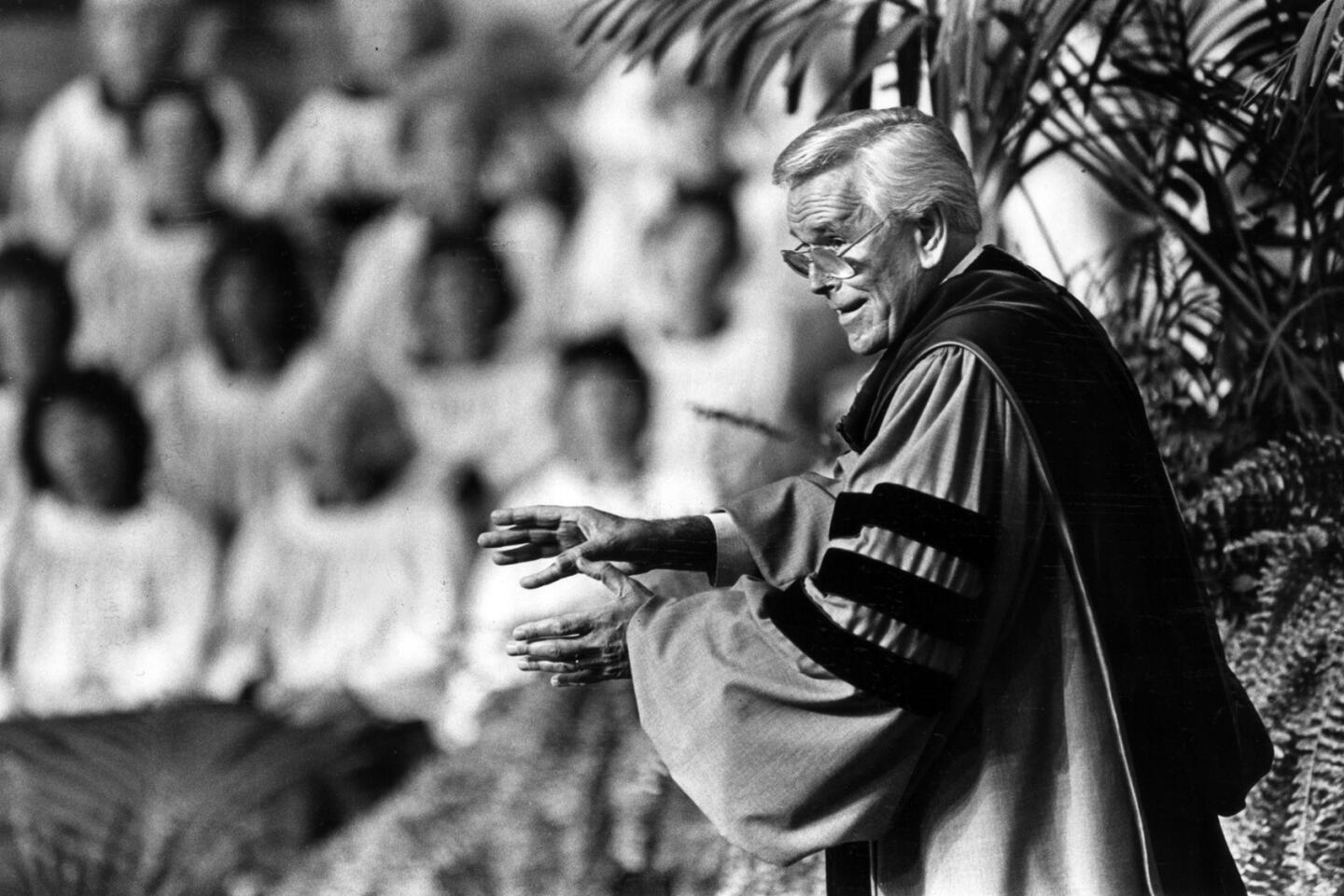

Some found his demeanor aloof, condescending and humorless. But when he donned his purple robe and took to the pulpit, he was a showman, bringing his brand of Christian eloquence to an audience ready to be wowed.

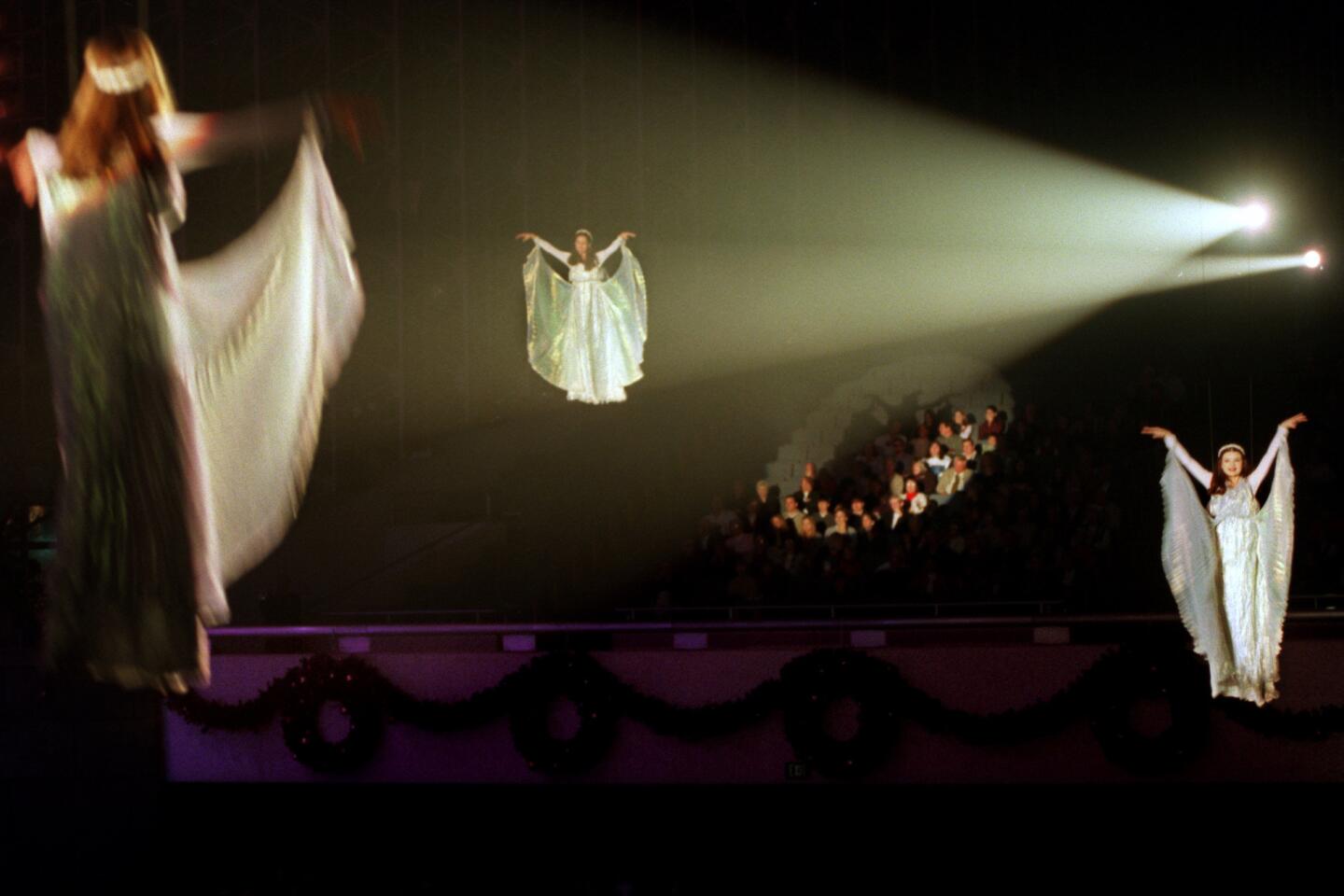

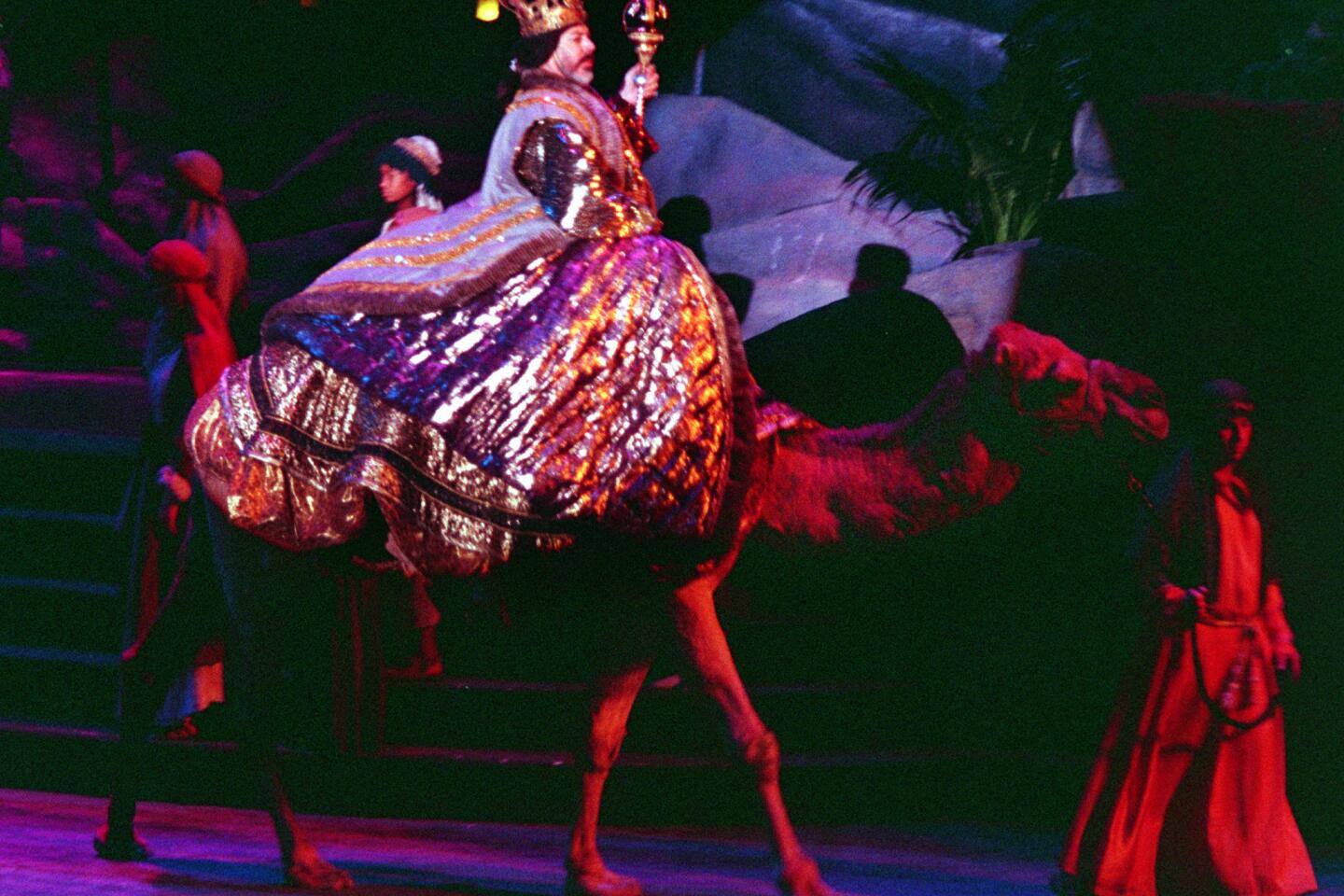

Over the years, though, as Southern California changed and his audience aged, the message lost its novelty. Celebrity appearances and big production values, trademarks of a Sunday at the Crystal Cathedral, were not enough to save the church.

The future, once so beckoning on the spring day, eventually caught up with Schuller and passed him by.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.