Big tides could trigger large earthquakes, study says

- Share via

Big tides could help push small earthquakes to grow into very large temblors, a new study published in the journal Nature Geoscience said Monday.

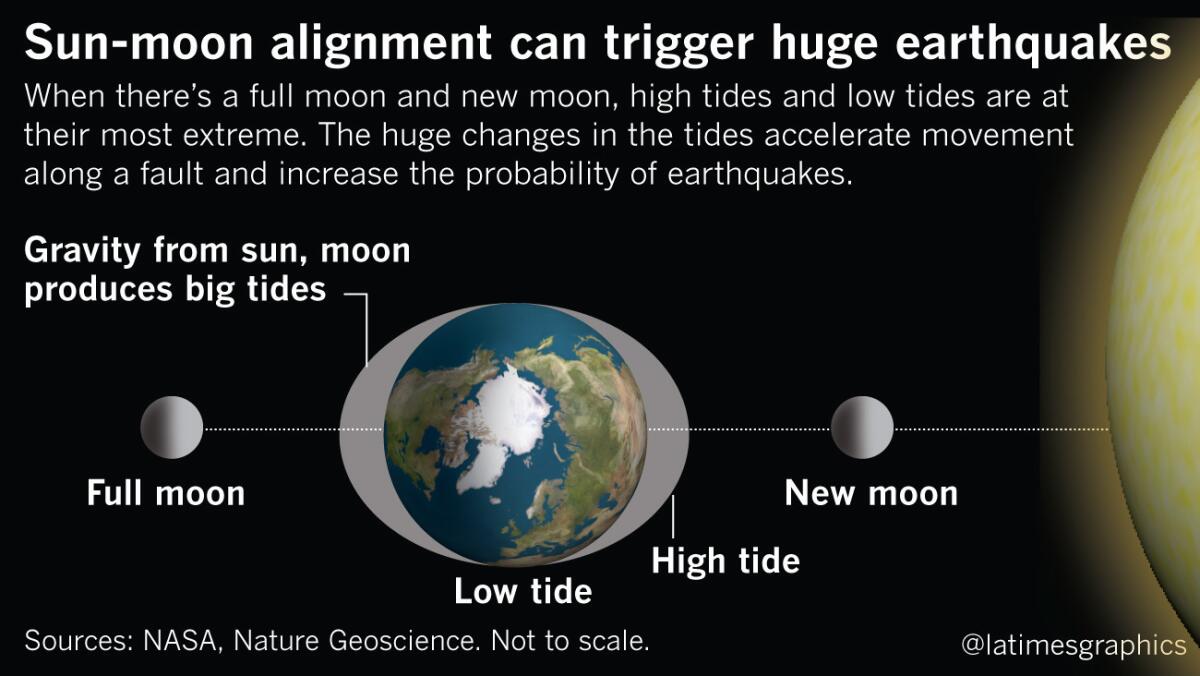

In a review of the world’s largest temblors, a team of Japanese scientists found that powerful earthquakes tend to occur during periods of strong tides, such as during the full moon and new moon, when the difference between high tide and low tide is greatest.

The idea that tides can affect earthquakes is not new. It makes sense; as oceans bulge a certain way when the sun, Earth and moon are all lined up, such as during the full moon and new moon, tidal forces can add more strain on earthquake faults.

But this study is the first to show a statistical connection that there are more powerful earthquakes than small earthquakes during periods of strong tides, said Satoshi Ide, professor of seismology at the Univeristy of Tokyo and the lead author of the study.

All earthquakes start very small. But the idea that’s presented in this study is that the added stress from a strong tidal force can help push a fault — already loaded up and strained to nearly its breaking point — over the edge, pushing a small earthquake to evolve into a monster.

“When tides are very large, small earthquakes tend to grow a little larger,” Ide said. The magnitude 9.1 Indonesia earthquake in 2004 and magnitude 8.8 earthquake in Chile in 2010, which both produced damaging tsunami, occurred around the time of a full moon, close to the peak time of tidal stress, the study said.

U.S. Geological Survey geophysicist Nicholas van der Elst, who was not affiliated with the study, said the observations documented were interesting and would prompt other scientists to see if they can replicate the results.

“Personally, I hope that this observation does pan out and is reproducable,” Van der Elst said. Studying how tides affect earthquakes, he said, helps explain “how earthquakes get started and how they get large.”

The primary cause of earthquakes is the Earth’s moving tectonic plates, which are constantly grinding against each other. Between the tectonic plates, strain builds up on faults until the pressure is released suddenly by an earthquake.

“The tides just add a little — 1% or less — additional push on top of that tectonic loading,” Van der Elst said. “Even though it’s a small contribution, it could be just the amount of stress that is the ‘straw that breaks the camel’s back,’ so to speak.

“So it makes sense that an earthquake would be more likely to happen, and coalesce into a larger earthquake, if there is just a little additional push,” he said.

To be sure, many earthquakes will still happen when tidal stress is low, Ide said.

“Earthquakes are nearly a random process,” he said. “Tidal forces are just a factor in a complex process. There are a lot of other factors.”

The relationship between strong tides and earthquakes has only been found in larger-magnitude earthquakes, and not in smaller events, and the reason why remains a mystery, Van der Elst said. A good test will be to see if the relationship presented in the study pans out in the coming years, he said.

But don’t think that this study means the next dreaded big earthquake on California’s San Andreas fault will hit during the full moon or new moon. (Tidal forces are felt on solid rock too — the solid rock of the Earth bulges toward the sun and the moon like ocean waters do.)

Think of it this way, Van der Elst said: “If you had 100 Big Ones on the San Andreas fault, you might see a tendency to see them a few more percent likely when the tides are aligned.

“The Big One on the San Andreas: It could happen during a full moon; it could happen any time,” he said.

The other two coauthors in the study, besides Ide, are Suguru Yabe and Yoshiyuki Tanaka, also of the University of Tokyo.

Twitter: @ronlin

To read the article in Spanish, click here

ALSO

What are the odds of dying in an earthquake?

Lucy Jones is leaving her job - to shake up more than just earthquakes

Deadly but little-known: Why scientists are so afraid of the San Jacinto fault

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.