Trump order upends future for a generation of Salvadorans who now must leave U.S.

An estimated 262,000 Salvadorans living in the U.S. will lose their “temporary protected status.”

- Share via

As they built their lives in the United States year after year, many Salvadorans considered their stay anything but temporary.

They were dishwashers who worked their way to being big-rig drivers, day laborers who became factory machinists. They got married, had kids, bought houses. El Salvador — its gang violence and suffocating poverty — seemed increasingly distant.

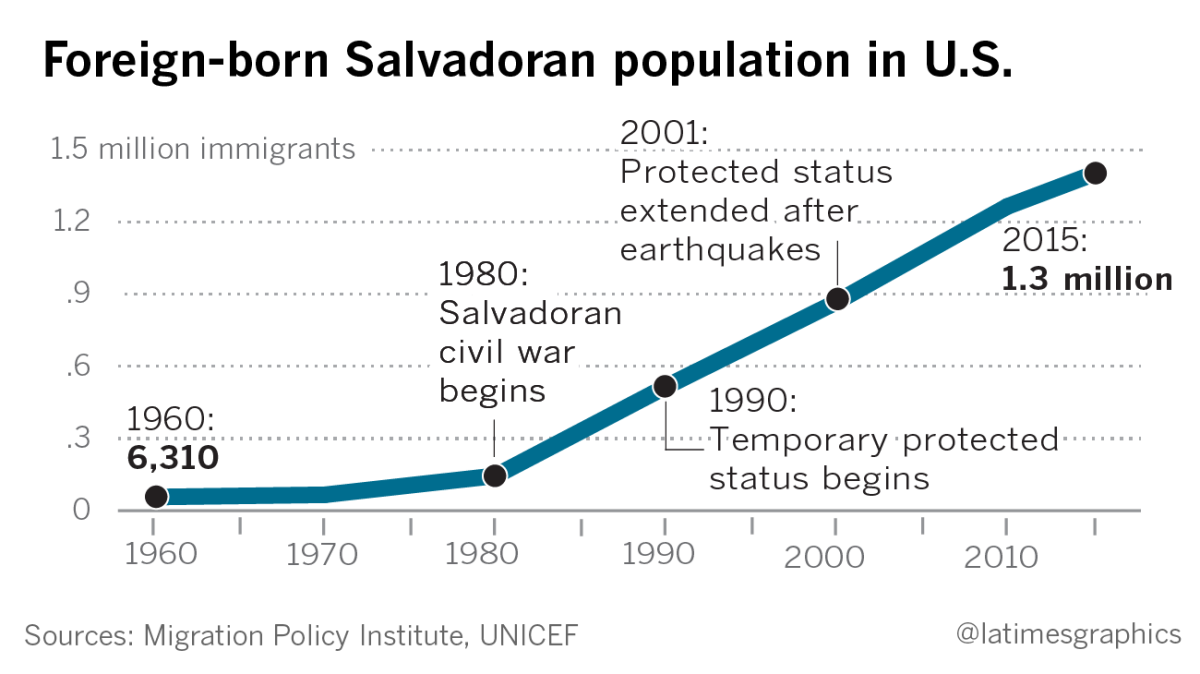

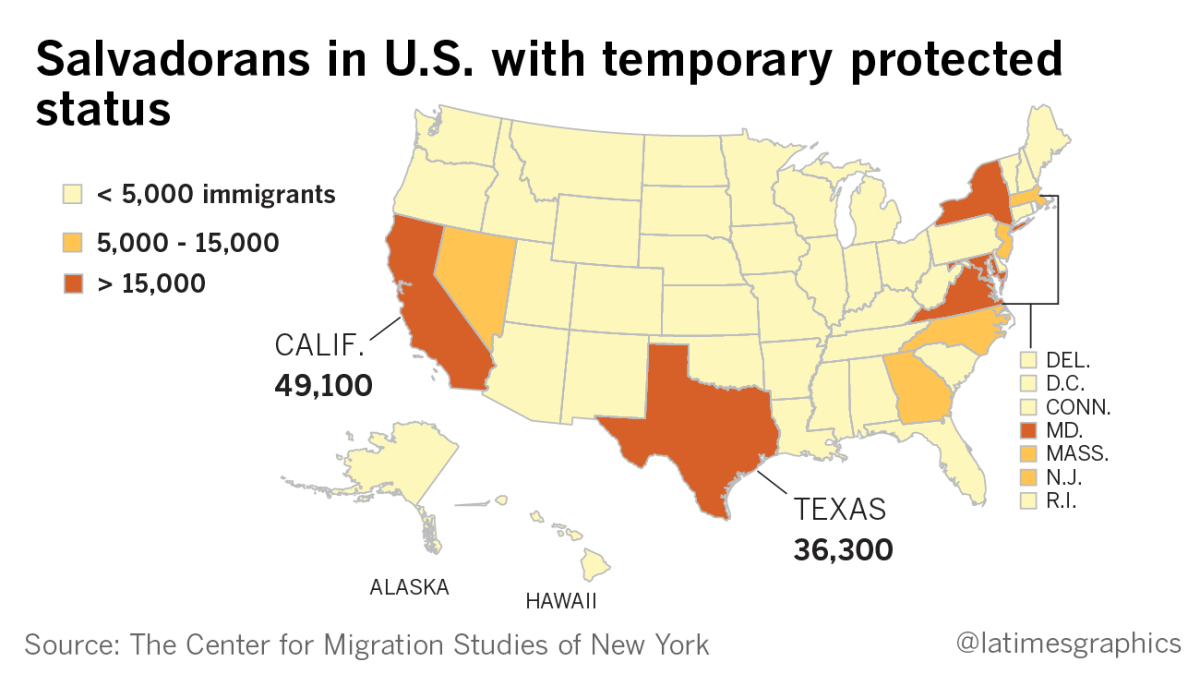

They viewed the temporary protected status program, known as TPS, as a stepping stone to residency. With the Trump administration’s decision Monday to rescind the program, some 262,000 Salvadorans — many of them with U.S.-born children — have 20 months from now to decide whether to return to the small Central American country, find another way to stay, or hide.

“It’s disappointing and it’s scary,” said Jose Guevara, 23, of Los Angeles, who got word Monday morning that his parents will be stripped of their immigration status. Guevara is battling leukemia and said his parents are his caretakers.

He said his mother has been in the United States for 15 years, his father for nearly 20. He fears they will be deported. “We thought this might happen,” Guevara said.

The Bush administration extended the special protections for Salvadorans in 2001, after two devastating earthquakes in El Salvador. But current administration officials say conditions in El Salvador have improved since then.

“Schools and hospitals damaged by the earthquakes have been reconstructed and repaired, homes have been rebuilt, and money has been provided for water and sanitation and to repair earthquake-damaged roads and other infrastructure. The substantial disruption of living conditions caused by the earthquake no longer exists,” Department of Homeland Security officials said in a statement.

Even so, the State Department website warns U.S. citizens of the dangers of travel to El Salvador, noting that the country has “one of the highest homicide levels in the world and crimes such as extortion, assault and robbery are common.”

For years, El Salvador has been racked by brutal gang violence, including from the MS-13 gang, which has gained a significant presence in the U.S.

But Homeland Security Secretary Kirstjen Nielsen decided that under the law she could consider only the original conditions that led to the granting of temporary status — the damage from the earthquakes 17 years ago.

Advocates for the immigrants immediately protested, calling the decision needlessly cruel and a blow to the economies of both El Salvador and the U.S.

In the nearly two decades during which they have been able to live and work legally in the U.S., Salvadorans with protected status have built careers and opened businesses, and workers now play a significant role in industries like construction and housekeeping. The economy of El Salvador also depends on money sent back to families from abroad — $4.5 billion last year.

“The United States has yet again turned its back on its promise to provide refuge for those who face violence and persecution in their home countries,” said Oscar Chacón, executive director of Alianza Americas, a network of immigrant rights groups.

“Our government is complicit in breaking up families — nearly 275,000 U.S.-born children have a parent” who has temporary legal status, he said. Studies have estimated that Salvadorans with temporary status have nearly 200,000 children who are U.S. citizens.

Congress created the temporary status program in 1990 to give the executive branch the authority to allow migrants from countries hit by natural disasters, wars or other emergencies to remain in the U.S. and work legally for a limited period of time.

But Trump administration officials say that because previous administrations have frequently extended the temporary stays, the program has improperly been allowed to become an all-but-permanent refuge. They have been determined to roll it back.

Last year, the Department of Homeland Security announced an end to temporary protections for Nicaraguans and Haitians, and put off making a decision affecting 60,000 Hondurans.

Rep. Jim McGovern (D-Mass.), who helped write the temporary status law, said the administration relied on a “distorted and narrow interpretation” to cancel the program. He called the move “a shameful and cynical move to punish these innocent families just to score political points with the extreme right-wing Republican base.”

Groups that lobby for curbing immigration — both illegal and legal— welcomed Trump’s move.

Federation for American Immigration Reform President Dan Stein said it was long overdue and called the numerous extensions “unjustified.”

“Today’s announcement underscores the temporary nature of TPS, and reminds us that it was never intended to be used as a tool to sidestep the legal immigration process,” Stein said in a statement. “‘Temporary’ clearly does not mean ‘forever.’”

Several bills have been introduced in Congress to allow people with temporary status to remain in the U.S., but no action is expected any time soon. Members of Congress may act in the next few weeks on another immigration-related issue — a permanent solution for the young immigrants who were shielded from deportation by the Obama-era Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals, or DACA, program — but officials in both parties consider further immigration action unlikely.

When Jose Siguenza left El Salvador 23 years ago, it was emerging from a civil war that had destroyed much of the country’s infrastructure. Unemployment was high, food expensive, gangs a rising threat.

“I left, because I wanted better living conditions,” said the 47-year-old Montebello man, who became a TPS recipient in 2001.

Siguenza works at a print shop and sends $300 a month to his family in El Salvador.

“If I were to return, I’d find it strange and a difficult thing,” Siguenza said. “I’ll feel like this is my native land, my country, but I’ll also feel like I don’t belong there.”

Five years ago, he said he was ready to open a photography business in Montebello but put the ambition on hold because his immigration status depended on the renewal of the TPS program. “I saw some people opening businesses and now they’re stuck because they don’t know what to do,” he said.

He said he’s weighing all options — getting a green card, hoping Democrats will take control of Congress. He said he considers America home: “I feel I’m part of it. We’re part of this system and our hearts are here.”

Sylvia Arevalo is a native of El Salvador and a naturalized U.S. citizen who runs a Santa Ana travel agency, restaurant and food market full of Salvadoran snacks, calling cards and knickknacks.

For years, Arevalo has helped people fill out their TPS applications. She said many had feared this day would come. “Now their worry is ‘What am I going to do?’” she said. “How are they going to work? Will they be let go from their jobs?”

Just before noon Monday, Pedro Torres, 40, peeked into Arevalo’s shop, thanking her for a package she’d sent for him to his family in El Salvador the week before.

Quickly, the conversation turned to the latest news.

“It went badly for us, Mrs. Sylvia,” Torres said.

“Yes, it did,” she said.

Torres, a TPS recipient who works as a restaurant cook with a work permit, said he will start looking for work in the underground economy. “I have no other choice,” Torres said.

Orlando Zepeda, a 51-year-old maintenance worker, arrived in the United States in 1984, fleeing the civil war in El Salvador.

Zepeda and his wife, Lorena, both TPS recipients, own a two-bedroom house in Los Angeles, and they have two U.S.-born children. Every Sunday, the family volunteers at a hospital, and at least once a month they serve breakfast to homeless people.

He said that while he knew that TPS was intended to be temporary, the government sent mixed messages by repeatedly extending the program. “Something temporary doesn’t last 16 years. That’s not temporary,” he said. “We didn’t think this would happen.”

Zepeda said he refuses to move his family to a country that feels less like home than like a dangerous foreign land. A few years ago, gang members killed his wife’s nephew for refusing to join their clique.

He said he’d do whatever he can to stay in America, even if it means finding a job in the underground economy. His 12-year-old daughter, Lizbeth, told him: “I don’t want them to separate us.”

“We’ve lost the battle, but the war hasn’t been lost,” he tried to assure her. “We’re going to fight.”

He hopes his employer will keep him on. “We’ve invested everything we have in this country,” he said. “I’ve been here for 33 years.”

Tanfani reported from Washington, D.C., Carcamo from Santa Ana, and Bermudez and Vives from Los Angeles.

esmeralda.bermudez@latimes.com

UPDATES:

5:40 p.m.: This article was updated with additional reaction, details and background.

This article was originally published at 12:15 p.m.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.