Must Reads: 87 days of smog: Southern California just saw its longest streak of bad air in decades

- Share via

Southern Californians might remember the summer of 2018 for its sweltering heat waves, record ocean temperatures and destructive wildfires. But it also claimed another distinction: the summer we went nearly three months without a day of clean air.

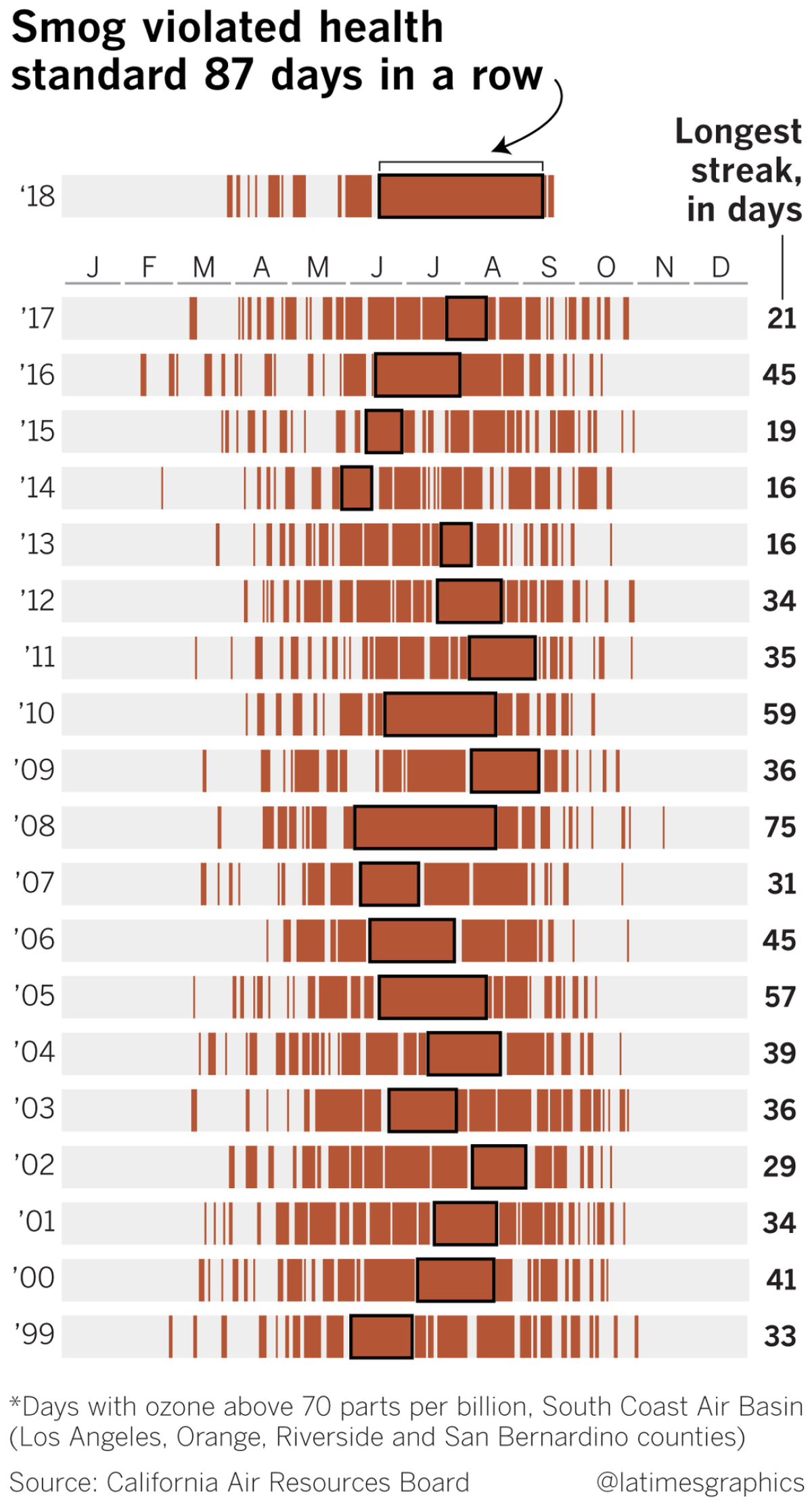

The region violated federal smog standards for 87 consecutive days, the longest stretch of bad air in at least 20 years, state monitoring data show. The streak is the latest sign that Southern California’s battle against smog is faltering after decades of dramatic improvement.

The ozone pollution spell began June 19 and continued through July and August, with every day exceeding the federal health standard of 70 parts per billion somewhere across Los Angeles, Orange, Riverside and San Bernardino counties. It didn’t relent until Sept. 14, when air pollution dipped to “moderate” levels within federal limits for ozone, the lung-damaging gas in smog that triggers asthma and other respiratory illnesses.

It’s not unusual for Southern California summers to go weeks without a break in the smog, especially in inland communities that have long suffered the nation’s worst ozone levels. But environmentalists and health experts say the persistence of dirty air this year is a troubling sign that demands action.

“The fact that we keep violating and having this many days should be a wake-up call,” said Michael Kleeman, a professor of civil and environmental engineering at UC Davis who studies air pollution.

The South Coast Air Quality Management District, which is responsible for cleaning pollution across the region of 17 million people, said that consecutive bad air days is an inappropriate way to gauge progress curbing ozone, that this smog season was not as severe as last year’s and had fewer “very unhealthy” days.

The U.S. Environmental Protection Agency judges whether the region meets Clean Air Act standards based on the highest pollution readings, not how long bad air persists. By federal metrics, air district officials argue they are making strides. The highest ozone levels recorded this summer, they point out, were lower than the previous year, and the smog season began later.

“By all accounts this year is not great, but it’s a little better than last year,” said Philip Fine, deputy executive officer for the South Coast air district.

The bad air spell follows an increase in smog over the last few years that has bucked a long-term trend of improving air quality and left officials searching for answers. In 2017, the region logged 145 bad air days for ozone pollution, up from 132 ozone violation days in 2016 and 113 the year before.

By the same measure, this smog season is on par with last year, with 126 ozone violation days logged through Monday, according to air district statistics.

The district could not say if there had ever been a stretch of bad air days longer than the one this summer. The agency does not track consecutive violations of federal health standards, a spokesman said, because it “is not a useful or meaningful metric to gauge ozone air quality trends.”

Not everyone agrees. Joseph Lyou, a South Coast air quality board member who heads the Coalition for Clean Air, said he’s concerned that although the intensity of Southern California’s air pollution has dropped, its longevity is increasing.

“It’s a disturbing trend no matter what the law says you’re accountable for,” said Lyou, who asked about the streak of bad air days at a public meeting earlier this month. “It’s telling us we have a persistent problem and that we still have a long way to go.”

Regulators blame the dip in air quality in recent years on hotter weather and stronger, more persistent inversion layers that trap smog near the ground. They’re also planning a study into whether climate change is contributing to the smog problem, as many scientists expect, due to higher temperatures that speed the photochemical reactions that form ozone.

Hotter weather from global warming is not accounted for in pollution-reduction plans required under the Clean Air Act, even though scientists expect it to hinder efforts to control smog.

“This is one example of the close ties between air pollution and climate change, which makes meeting air quality standards even more challenging and illustrates the urgency for addressing climate change at all levels of government in the U.S. and globally,” said Barbara Finlayson-Pitts, an atmospheric chemist at UC Irvine who studies air quality.

Lyou worries that a failure to account for climate change could pose another obstacle to meeting federal ozone-reduction deadlines in 2023 and 2031. The air district’s latest cleanup plan says the region can get there only by increasing local, state and federal cash incentives for lower-polluting vehicles by more than tenfold to $1 billion a year. But so far, it’s falling far short.

Environmentalists and community groups say the string of smoggy days is a symptom of insufficient regulation. They criticize air quality officials as too quick to blame the weather when they could be doing more to crack down on some of the biggest hubs of pollution, including truck-choked warehouses and ports and oil refineries.

“We know that it’s getting hotter and drier from climate change, but the law says we need to breathe clean air no matter the weather,” said Adrian Martinez, an attorney for the environmental law nonprofit Earthjustice who chronicled the mounting number of ozone violations from his Twitter handle @LASmogGuy.

“The last time we met the standard, Justice Kennedy had not announced retirement yet & the World Cup just started,” Martinez tweeted on Sept. 7, some 80 days into the spell. “This isn’t right. Our lungs deserve better.”

Experts say the unsteady progress in Southern California is expected, and a reflection of the difficulties in controlling ozone, which is not emitted directly but forms when combustion gases and other pollutants react in the heat and sunlight. The formation of smog is so influenced by weather conditions and the precise mix of pollutants in the air that scientists and regulators are not surprised to see ozone pollution tick up, despite a long-term trend of declining emissions.

“As we work to bring the whole region down, we’re actually seeing some areas where the ozone production is getting more efficient,” said Kleeman, who thinks scientists should reconsider the effectiveness of control measures and whether targeting different types of pollutants could bring swifter reductions.

“Are we really doing the right things for the right reasons and is it having the effect that we think?” Kleeman said.

At the same time, health scientists are publishing more research linking ozone and other regional air pollutants to a wider array of health problems at levels well below regulatory limits. Such findings, they say, underscore the need to do as much as possible to curb smog and ease the number of asthma attacks, missed school days, emergency room visits and premature deaths — all of which increase when ozone pollution is high.

“There’s no question that people with preexisting lung diseases, particularly asthmatics, have had a harder time this year than they would have in previous years where there weren’t so many exceedances,” said Michael Jerrett, who chairs the Department of Environmental Health Sciences at UCLA’s Fielding School of Public Health.

Such problems can be most acute in the smoggy Inland Empire. There, some are starting to view past success cleaning air pollution as an impediment to easing its health damage today. They say clearer mountain views can belie the fact that the air still exceeds health limits for much of the summer.

Smog’s less visible presence can make it easier to live in denial about the health effects, said John Cadavona, a registered respiratory therapist who supervises Arrowhead Regional Medical Center’s Breathmobile, a fleet of RVs that treat schoolchildren in San Bernardino County, where asthma rates and ozone pollution are both high.

“We have parents that think that a cough that their child has is normal, when it may be asthma,” Cadavona said. “If we had cleaner air, we’d have kids who were healthier, whose lungs can function normally and can play sports without having to take medication.”

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.