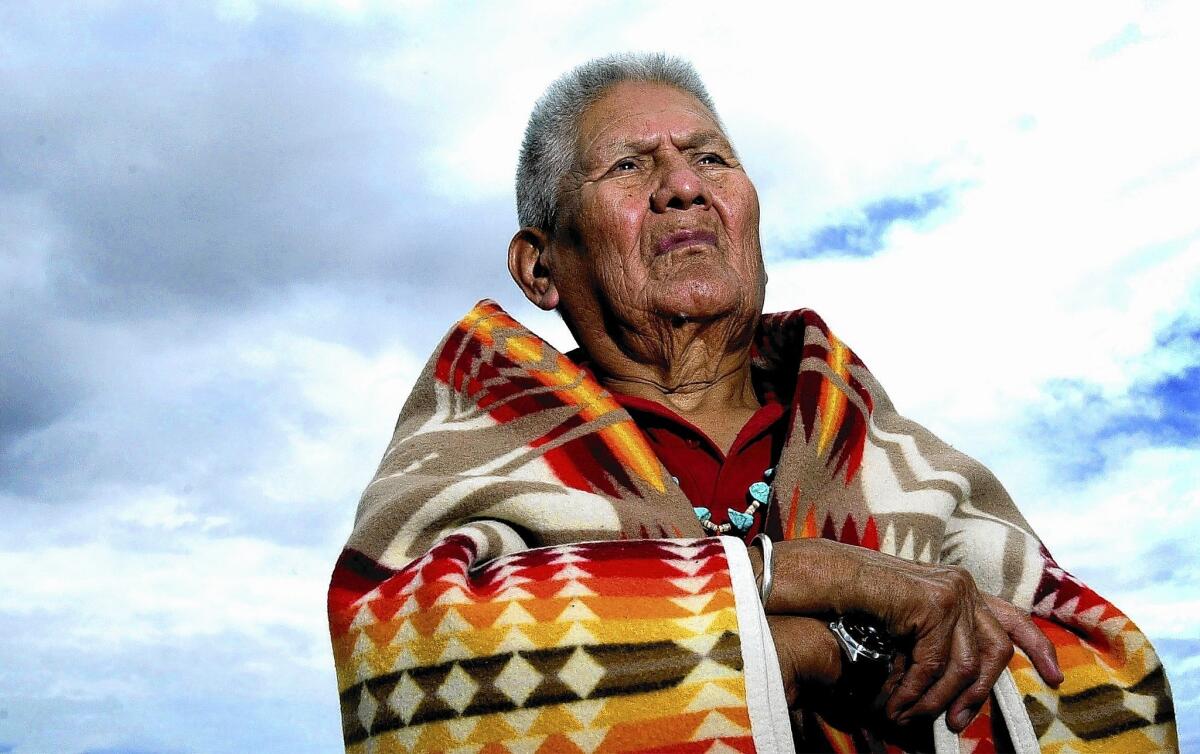

Chester Nez, last of WWII’s original Navajo code talkers, dies at 93

- Share via

If Chester Nez dared to use his Navajo language in school, punishment was swift and literally distasteful. He had to scrub his tongue with a toothbrush and wash out his mouth with bitter soap.

So he was intrigued when recruiters from the U.S. Marines showed up in 1942 seeking young men like him who knew both English and Navajo.

That day, four months after Japanese bombs fell on Pearl Harbor, Nez helped form an elite, top-secret group that became known as the Navajo code talkers. Using the Navajo language, they developed an unbreakable military communications code, then risked their lives on battlefields across the Pacific to send and decipher messages critical to America and its allies in World War II.

He didn’t have to volunteer; barred from voting, Native Americans were barely considered citizens. But Nez’s heritage spoke louder than decades of rejection. “I reminded myself that my Navajo people had always been warriors, protectors,” he wrote years later. “In that there was honor. I would concentrate on being a warrior, on protecting my homeland.”

Nez, the last of the original 29 code talkers, died Wednesday in Albuquerque. He was 93 and had kidney failure, said Judith Avila, who helped Nez write his 2011 memoir, “Code Talker.”

In 2001 he received the Congressional Gold Medal, Congress’ highest civilian honor, from President George W. Bush.

One of five children, Nez was born Jan. 23, 1921, in Two Wells, N.M. His mother died when he was about 3. When he was about 9, his struggling father packed him off to government boarding schools to learn English and other skills that might help him succeed among whites.

The Marines showed up at his high school in Tuba City, Ariz., in the spring of 1942. The recruiters did not say why they needed Navajos, but the promise of adventure appealed to a teenager whose future otherwise seemed to offer little more than growing corn and beans or tending sheep.

“The Navajo feeling is to go to the top of the hill and see what’s on the other side,” he told The Times in 2001.

He left immediately for basic training at Camp Pendleton. After boot camp, he and the other 28 Navajos chosen for the project were sent to Camp Elliott in San Diego. It was there that they learned the daunting nature of their assignment.

The Japanese had already broken every code used by the Allies, so when Philip Johnston, a World War I veteran who had grown up on a Navajo reservation, proposed using the Navajo language as the basis for a new code, the top brass thought it was worth a try.

In many respects, Navajo was perfect for the task: It had no written form, used complicated syntax and had unusual tonal features that added another layer of difficulty.

For 13 weeks Nez and his fellow recruits were confined to a room at the base where they were instructed to come up with words to represent the letters A to Z as well as a code for military terms. At first “everybody thought we’d never make it,” Nez recalled. “It seemed impossible because even among ourselves, we didn’t agree on all the right Navajo words.”

But the code finally emerged.

“Wol-la-chee,” the Navajo word for “ant,” represented A, “na-hash-chid”, the word for “badger,” was B, “moasi,” the word for “cat,” was C, and so on. For key military words, they relied on easy-to-remember images. So “a-ye-shi,” the word for “eggs,” for example, meant “bombs.” “Ni-ma-si,” or “potatoes,” signified “grenades.”

Once they agreed on the code, they began to practice it, demonstrating speed and accuracy. Messages that had taken 30 minutes to code and decrypt using other systems were translated and deciphered in 20 seconds by the Navajo code talkers.

The first message Nez transmitted was at Guadalcanal in November 1942: “Enemy machine gun nest on your right. Destroy.” The Allied forces blasted the target.

After Guadalcanal, Nez never stopped moving, encrypting, relaying and deciphering messages about enemy positions, Allied strategy, casualties and supplies — at the Battle of Bougainville in New Guinea in November 1943, Guam in July 1944 and Peleliu and Angaur in September 1944. The code talkers were so vital to the war effort that they were not permitted leaves.

“We were almost always needed to transmit information, to ask for supplies and ammunition and to communicate strategies,” Nez wrote in his memoir. “And after each transmission, to avoid Japanese fire, we had to move.”

Ultimately 400 Navajos served as code talkers. They were crucial to the campaign on Iwo Jima, conveying and decoding 800 messages without error in the first 48 hours of the operation. “Were it not for the Navajos, the Marines would never have taken Iwo Jima,” according to a memo by Maj. Howard Conner, a 5th Marine Division signal officer.

Nez avoided serious injury but was once threatened at gunpoint — by a fellow GI who thought he was a Japanese soldier.

He remained in the Marines through the Korean War. But civilian life proved difficult at times. The code talkers were forbidden to talk about their activities for more than two decades, until their mission was declassified in 1968. Nez avoided veterans parades and had nightmares about Japanese soldiers and the carnage he witnessed.

For many of his fellow code talkers, the secrecy order made it hard to get a job; they couldn’t tell employers what they had done during the war.

“Chester was one of the lucky ones,” Avila said in an interview Wednesday. “He got an interview at the VA hospital in Albuquerque and was hired to be a maintenance guy. He was a painter. Sometimes he painted lovely things,” including murals depicting Navajo culture. He retired in 1974.

He is survived by sons Michael and Tyah, nine grandchildren and 11 great-grandchildren.

“I worried every day that I might make an error that cost American lives,” Nez told CNN a few years ago. “But our code was the only code in modern warfare that was never broken. The Japanese tried, but they couldn’t decipher it. Not even another Navajo could decipher it if he wasn’t a code talker.”

More to Read

Start your day right

Sign up for Essential California for the L.A. Times biggest news, features and recommendations in your inbox six days a week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.