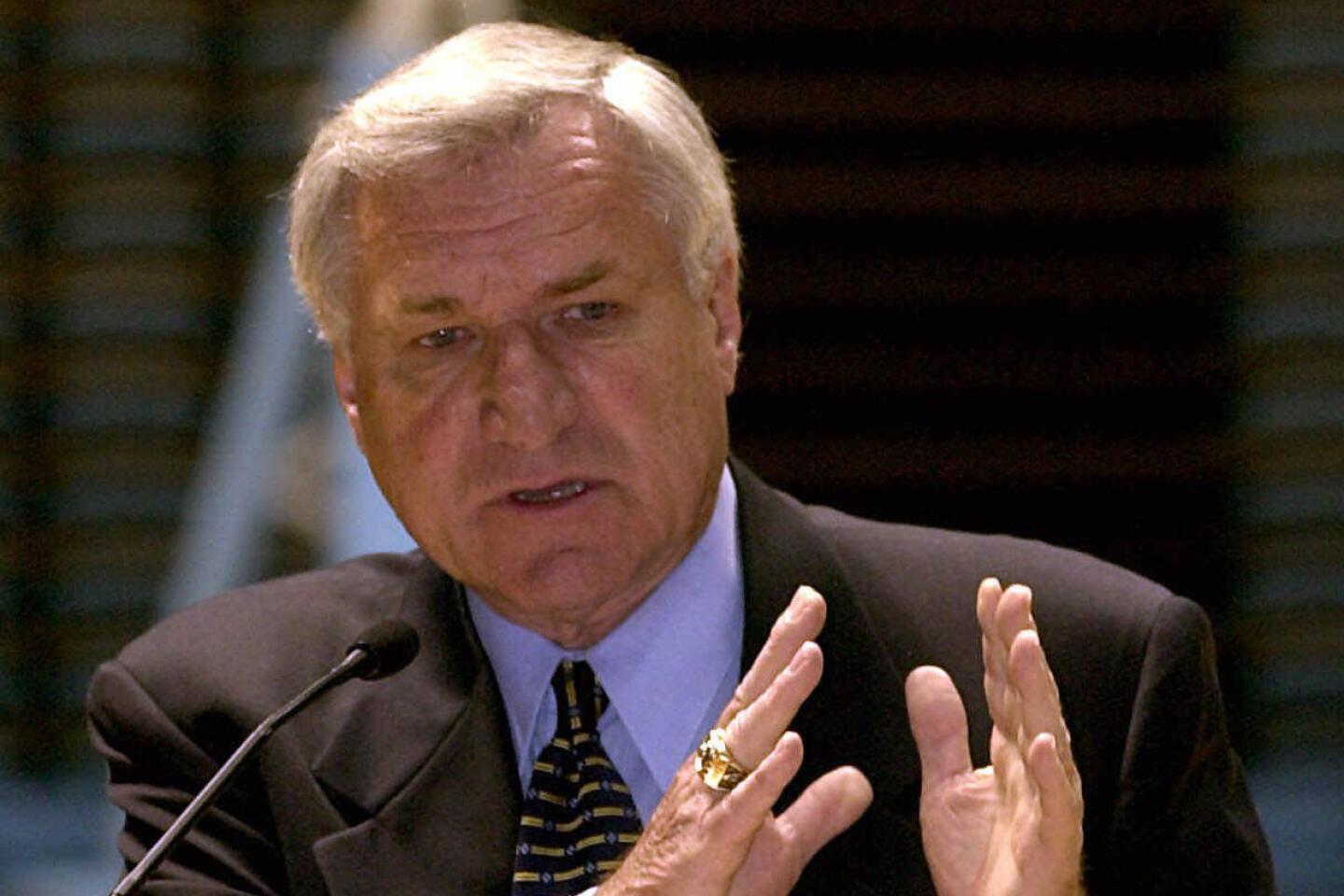

Dean Smith dies at 83; North Carolina basketball coaching legend

- Share via

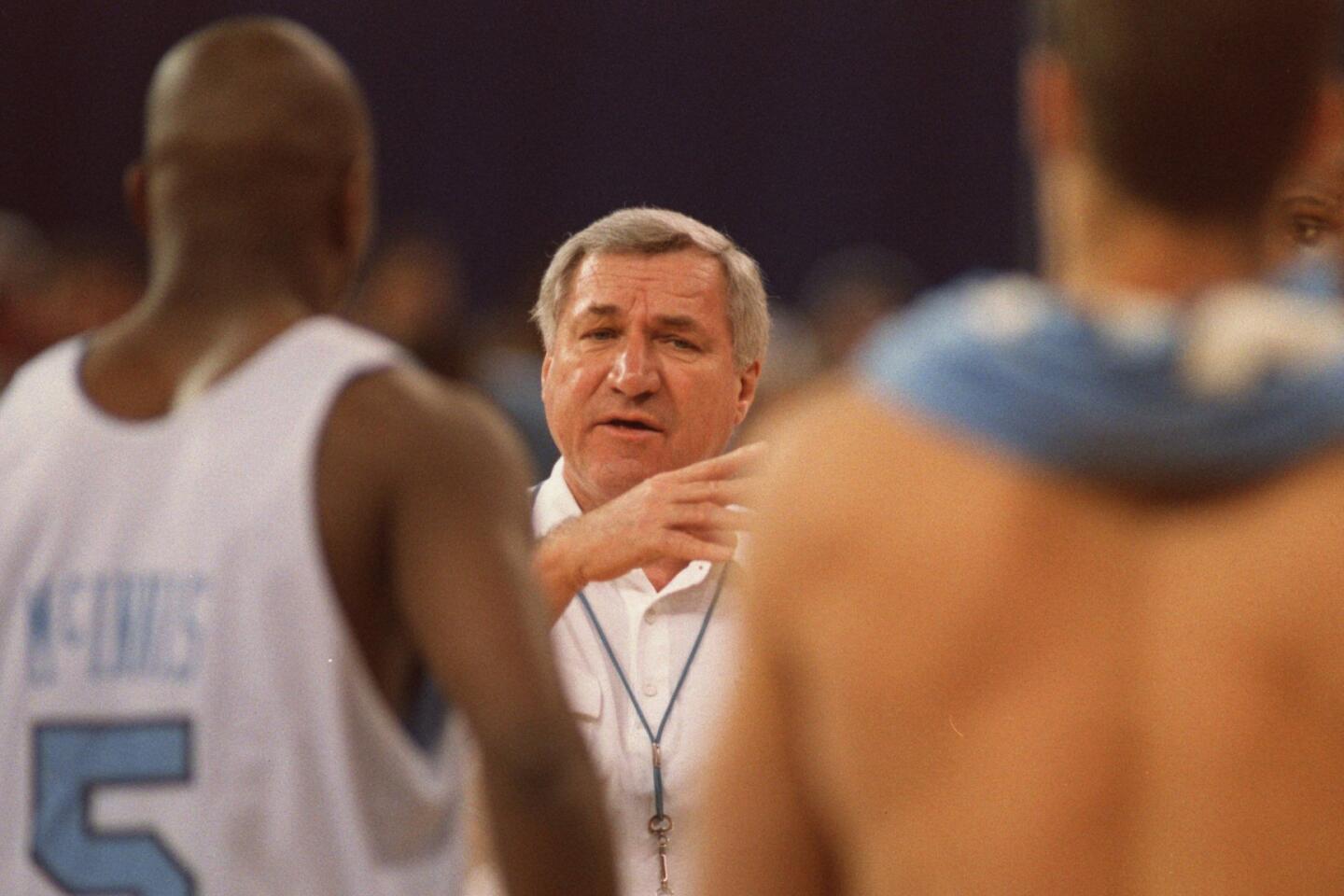

A blue line, 10 inches wide, awaited North Carolina basketball players at the arena’s entrance each day before practice.

They knew it as the spot where competition began. It was to be crossed only after both shoes were tied, practice jerseys were properly tucked, and minds were prepared.

It was just a line on the floor, but it was also much more: It was a metaphorical

border of what celebrated coach Dean Smith called “the Carolina Way” — a sense of humility, teamwork and just plain hard work that came to be seen as

the university’s ideal.

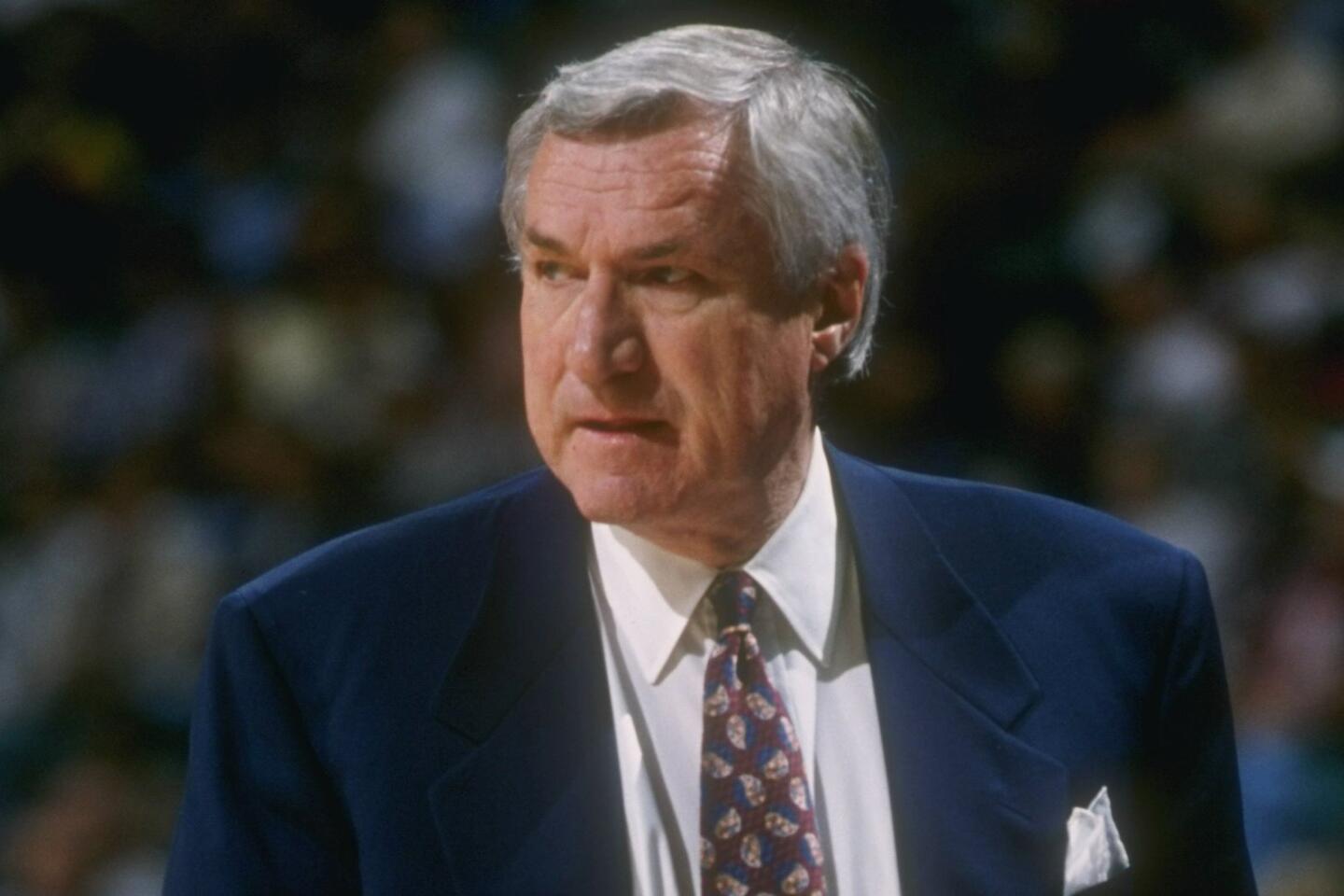

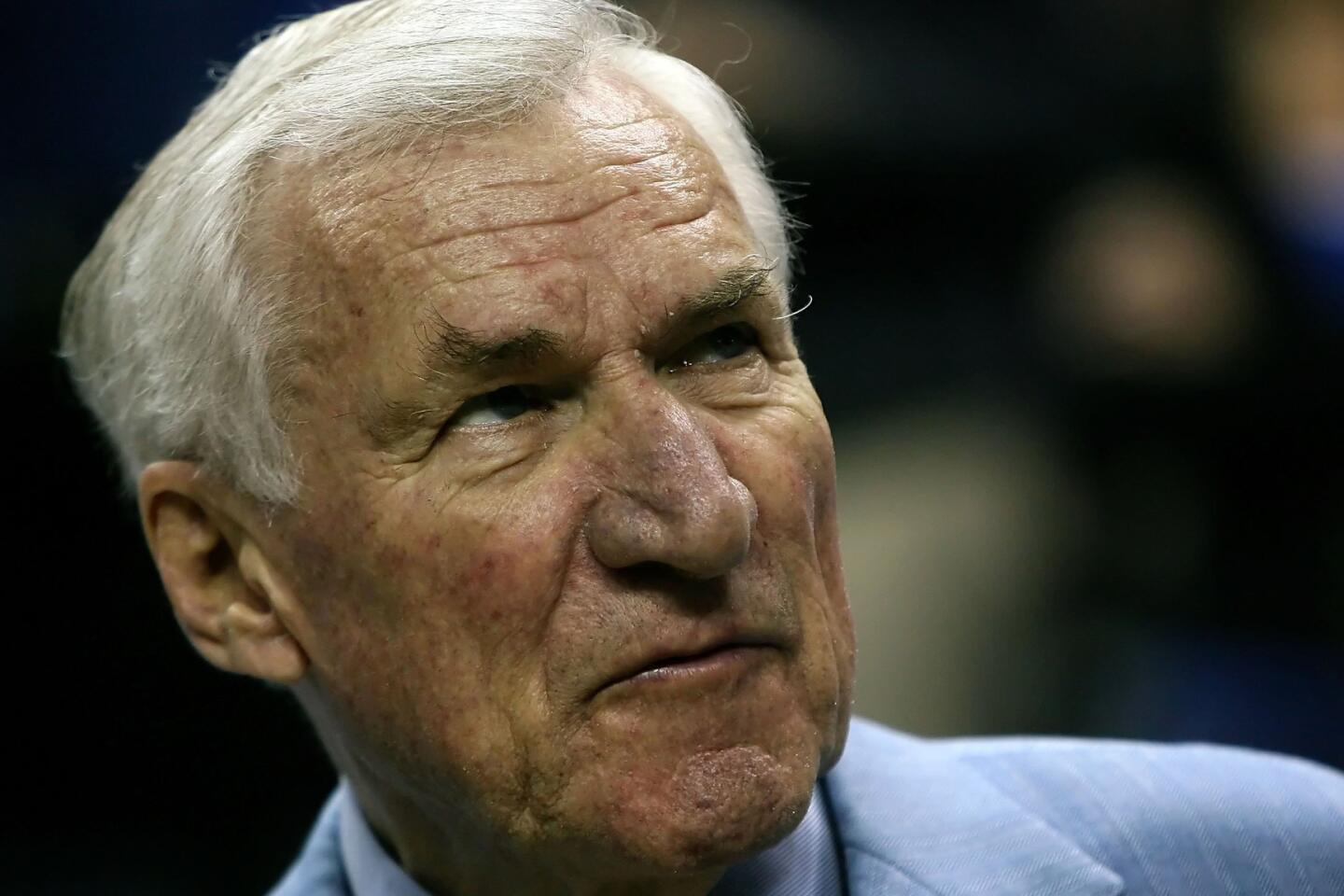

Smith, a beloved basketball figure who used fundamentals and team-first dictates to lead the University of North Carolina men’s basketball team to sustained success, died Saturday night at his home in North Carolina, the university announced. He was 83.

No cause of death was given, but his family disclosed in 2010 that he was suffering from a progressive neurological disorder.

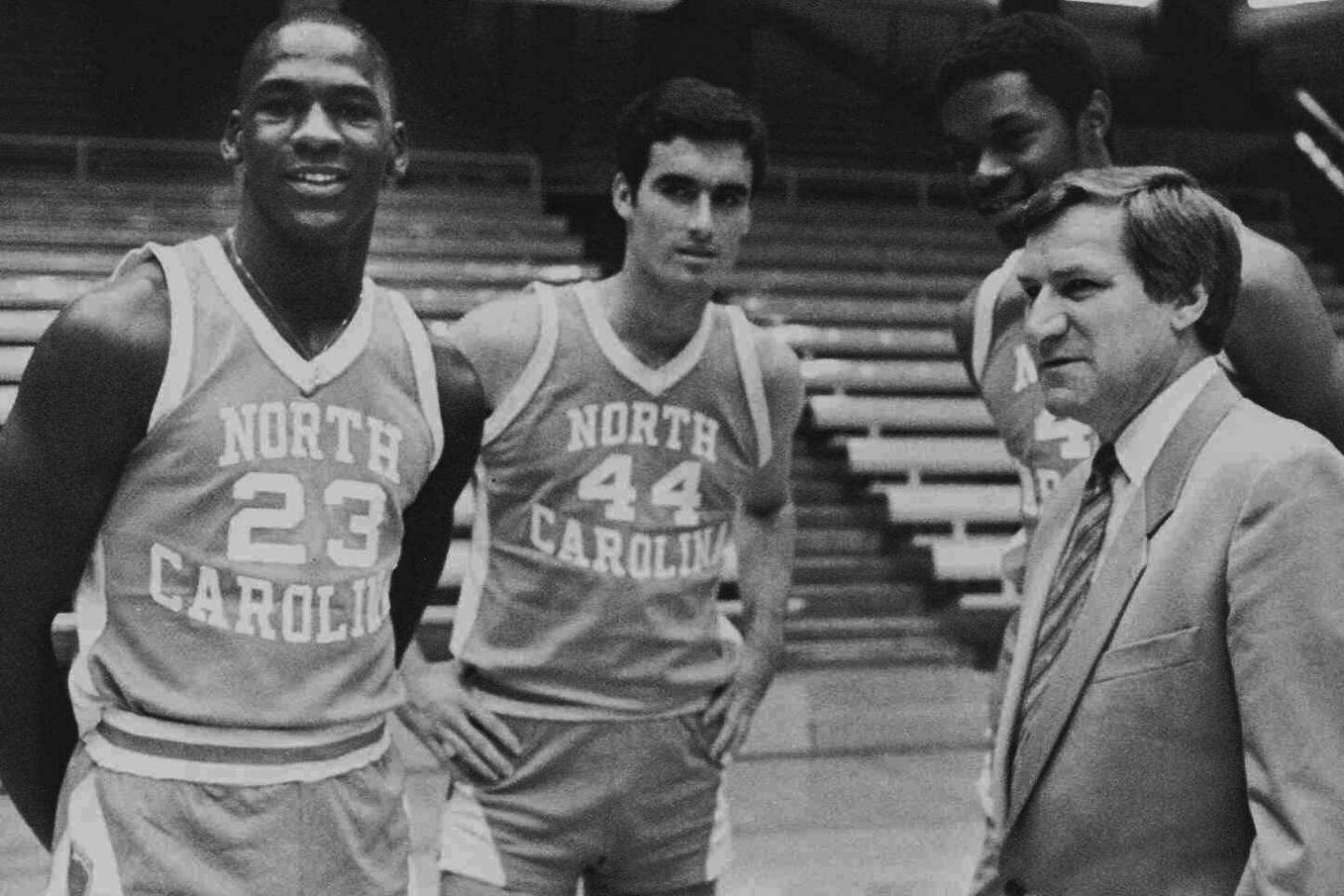

Smith mentored many of the game’s greatest players and coaches, from Michael Jordan to Larry Brown, and championed civil rights in the South during the segregated 1960s.

In 1997, he retired with 879 victories at North Carolina, a collegiate record until Bob Knight eclipsed it 10 years later.

Smith led North Carolina to 11 Final Four appearances, 17 regular-season Atlantic Coast Conference titles and 23 consecutive NCAA Tournament appearances.

He, Knight and Pete Newell are the only men to have coached teams to Olympic, National Invitation Tournament and NCAA championships.

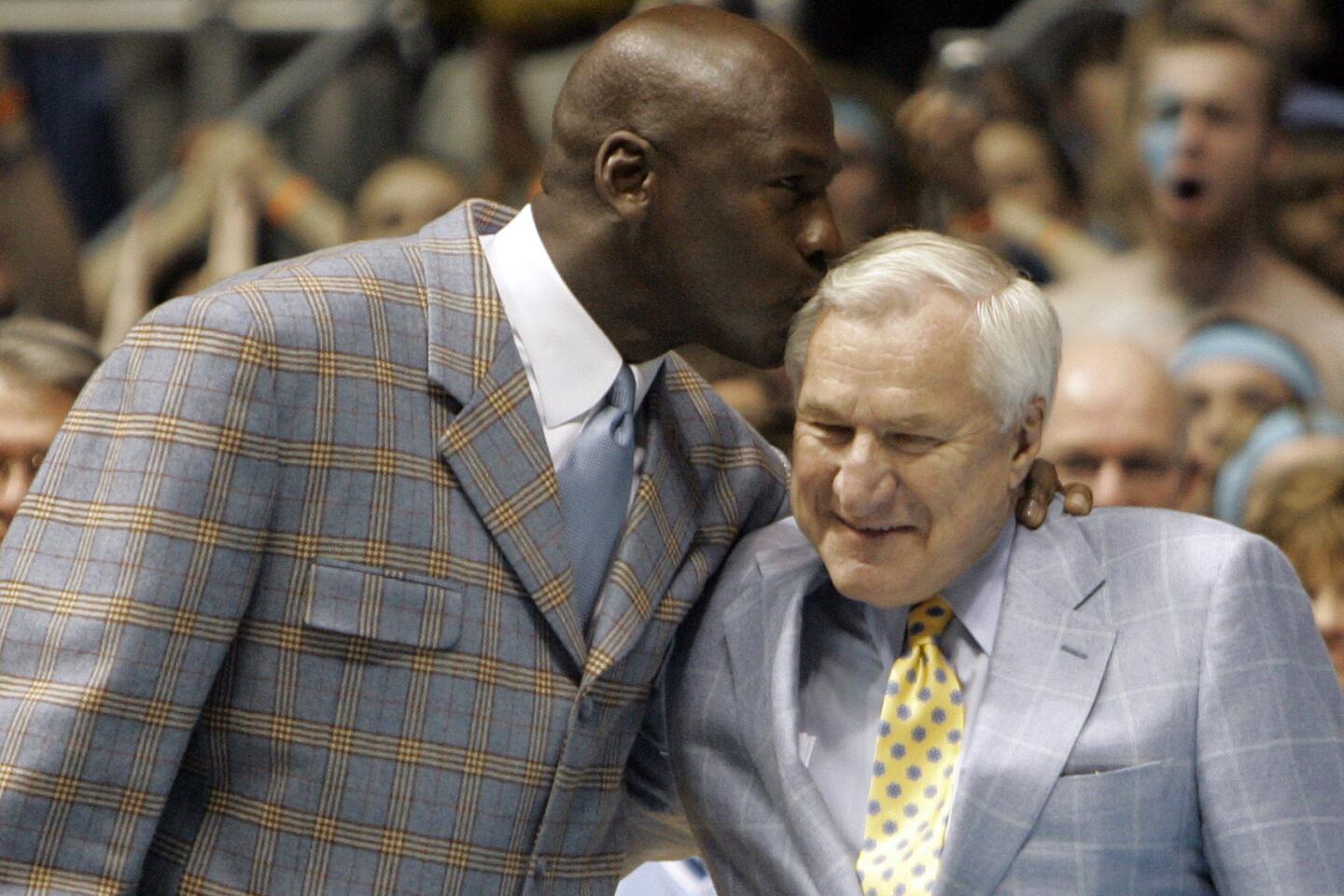

Smith mentored dozens of future NBA stars, including Jordan — considered by many the greatest basketball player ever — James Worthy, Sam Perkins, Billy Cunningham and Bobby Jones.

“Other than my parents, no one was a bigger influence in my life than coach Smith,” Jordan said in a statement released Sunday. “He was more than my coach — he was my mentor, my teacher, my second father.”

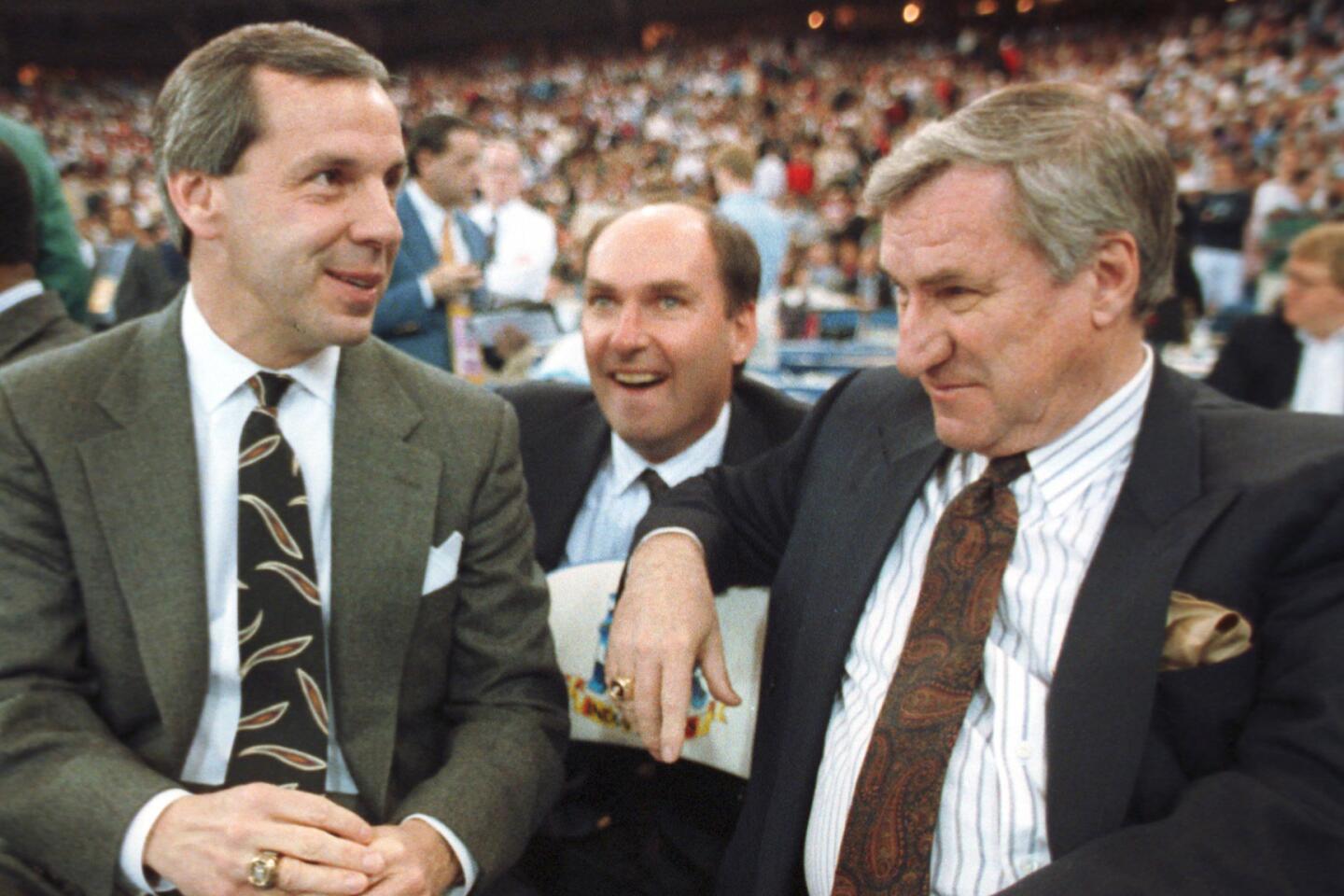

Lakers General Manager Mitch Kupchak, who played for Smith, said he leaned on his former coach years after leaving North Carolina.

“His influence on my life didn’t end when I left Chapel Hill,” Kupchak said in a statement, “as he was a trusted and valuable advisor to me when I became a player, then an executive in the NBA.”

Smith considered himself foremost a teacher. Playing at the University of Kansas for legendary Coach Phog Allen, a disciple of James Naismith, Smith had direct lineage to basketball’s peach-basket origins.

Smith won two NCAA titles — eight fewer than UCLA Coach John Wooden, and half as many as archrival Mike Krzyzewski at Duke — yet his contributions to the game were considered second to none.

“I think Dean is the best teacher of basketball that I have observed,” Wooden once said.

Many celebrated coaches were weaned under Smith, including Brown, Cunningham, Roy Williams, Doug Moe and George Karl.

But he believed in more than X’s and O’s. He was an articulate advocate for social causes, a Democrat in the conservative South who opposed the death penalty and the wars in Vietnam and Iraq.

“I tried to be careful which torches I carried, as well as judicious in the comments I did make,” Smith wrote in his 1999 memoir, “A Coach’s Life.”

Smith fought to integrate Chapel Hill restaurants and, in 1966, signed Charles Scott, the first African American athlete to receive an athletic scholarship at North Carolina.

“Coach Smith showed us something that I’ve seen again and again on the court,” President Obama, an ardent player himself, said Sunday. “That basketball can tell us a lot more about who you are than a jump shot alone ever could.”

Smith was a progressive Baptist who guarded his privacy, a chain smoker who didn’t curse publicly but enjoyed adult beverages and, on the court, occasional dust-ups with opposing coaches.

He preached selflessness, and it applied to everyone. Jordan, one of basketball’s most prolific scorers, averaged 19.6 points per game his junior year at North Carolina, prompting the joke that Smith was the only man alive who could hold him to under 20.

Smith was credited with many basketball innovations: Tar Heel players were the first to point to the assist man after scoring a basket. Players could ask out of a game by clenching a fist, with the guarantee they could re-enter after they were rested. Smith was the first to use multiple defenses during a game and, taking his cue from tennis players, made his players wear wrist bands to keep the sweat off their hands.

One of Smith’s most controversial contributions, a stall formation known as the “Four Corners” ball-control offense, helped lead to the advent of a shot clock in 1985 to speed up the game.

Success did not come early or easily for Smith’s teams. It took seven trips to college basketball’s Final Four tournament before he won his first national championship, in 1982, and an additional 11 years before he captured his second.

But Smith was in it for reasons that transcended championships. He spoke in his memoir about the quest of the dream.

“It was about the thousands of small, unselfish acts,” he wrote, “the sacrifices on the part of the players that resulted in team building.”

Born Feb. 28, 1931, in Emporia, Kan., Dean Edwards Smith was one of two children of schoolteachers Vesta and Alfred Smith. His mother was also a church organist, and his father coached football, basketball and track at the local high school. In 1934, Alfred Smith broke precedent by allowing a black teenager on his football team.

Dean graduated from high school in Topeka and made the University of Kansas basketball team, where he was a seldom-used guard. Coach Phog Allen urged him to become a doctor.

“Don’t go into coaching,” Allen told him. “Too many ups and downs. Too much heartache.”

After graduating with a bachelor’s degree in mathematics and physical education, marrying Kansas student Ann Cleavinger and then completing a two-year stint in the Air Force, Smith became an assistant basketball coach on Bob Spear’s Air Force Academy staff.

In 1958, he became an assistant to Frank McGuire at North Carolina, which was coming off a national championship season. Smith admired McGuire’s flamboyant style and lavish recruiting trips to New York.

But McGuire, it turned out, was loose with his bookkeeping and was targeted by the NCAA for “excessive recruiting expenditures.” The school was hit with probation that included a year’s banishment from the NCAA Tournament.

When McGuire left to coach the NBA’s Philadelphia Warriors, the 30-year-old Smith was named North Carolina’s coach. Chancellor William Aycock told him his job was safe as long as he did not embarrass the university. Smith never ran afoul of the NCAA and, over his 36 years as coach, graduated 96.6% of his players.

He also won 77.6% of his games, although no one, in the early years, predicted a powerhouse.

In 1961, North Carolina finished 8-9 in Smith’s first, and only, losing season. His record after four years was a modest 50-36.

Smith’s deployment of the Four Corners stall offense often drew ire, particularly when he used it in a 21-20 loss to Duke in the 1966 Atlantic Coast Conference Tournament.

“We heard a lot of boos, and some debris was even thrown on the court,” Smith recounted in his memoir. “...We didn’t want a good game. We wanted to win.”

Tar Heel basketball found its footing under Smith in 1966, a 26-6 season that started a streak of three straight Final Four appearances. It was also the year North Carolina broke the color divide by signing Charles Scott.

Scott, who became a trailblazer for minority athletes in the South, recalled two coaching assistants having to restrain Smith when someone at a game with the University of South Carolina hurled a racial slur.

“It was the first time I had ever seen Coach Smith visibly upset, and I was shocked,” Scott told Sports Illustrated. “But more than anything else, I was proud of him.”

Smith had earlier helped integrate a Chapel Hill restaurant by walking in with a pastor and a black student and ordering a meal.

North Carolina’s success in the late 1960s was overshadowed by UCLA’s basketball dominance. UCLA was in the midst of a seven-year NCAA title streak when North Carolina, in 1967, made its first of three straight Final Four appearances.

Smith and Wooden met only once for the title, in 1968, with UCLA easily winning, 78-55.

It took Smith more than 20 years to reach the top. He coached North Carolina to the NIT championship in 1971 and led the United States’ gold-medal effort at the 1976 Summer Olympics in Montreal, but lost NCAA title games in 1977 and 1981.

Smith finally claimed his first title in 1982 against Georgetown, on a game-winning jump shot by a freshman named Michael Jordan, who would leave for the NBA after his junior season.

“There’s no way you guys ever would have got to see Michael Jordan play without Dean Smith teaching me the game,” Jordan said in 2009 when he was named to the Naismith Basketball Hall of Fame.

In 1993, Smith won his second national title with a 77-71 victory against Michigan.

In the spring of 1997, Smith was fast approaching Kentucky coach Adolph Rupp’s all-time mark of 876 wins, a record Smith had so little interest in breaking he had to be talked out of retirement before the season.

“I don’t think they should even keep coaching records,” he said in his memoir. “The records belong to the players.”

Smith beat Rupp’s mark in March 1997 against Colorado in the NCAA Tournament. He retired the following October, at age 66.

Smith’s second wife, Linnea, accepted the Presidential Medal of Freedom on Smith’s behalf in 2013. She survives him, along with son Scott; daughters Sandy, Sharon, Kristen and Kelly; and several grandchildren.

More to Read

Start your day right

Sign up for Essential California for the L.A. Times biggest news, features and recommendations in your inbox six days a week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.