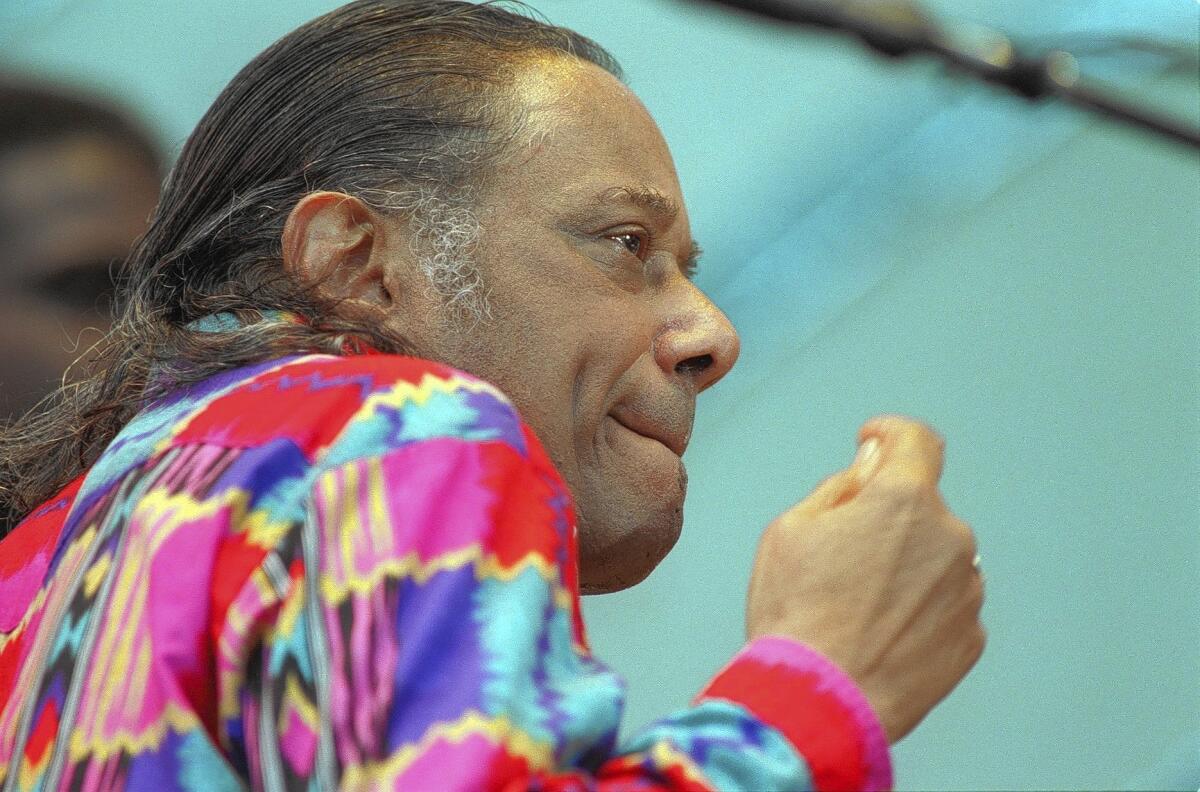

Horace Silver dies at 85; pioneering jazz pianist and composer

- Share via

Horace Silver, the prolific jazz pianist and composer who cofounded the legendary Jazz Messengers, pioneered the genre known as hard bop and mentored scores of musicians, has died. He was 85.

Silver died Wednesday at his home in New Rochelle, N.Y., of natural causes, according to his son, Gregory.

Through classic compositions such as “Song for My Father,” “Nica’s Dream” and “Señor Blues,” Silver influenced generations of musicians with a style that encompassed all his musical loves: gospel, blues, Latin rhythm. It was music that, in Silver’s words, “cooked” and “burned.”

His works also kept Silver contemporary: a bridge between the jazz greats of his generation and musicians who weren’t even born when he began recording.

“As far as playing, composing, band leading, arranging, Horace Silver’s got to be one of the most influential musicians in the history of jazz,” said bassist Christian McBride. “No matter what style of jazz that you tend to gravitate toward, Horace Silver always touches you.”

Throughout his decades-long career, Silver fought against what he called getting “hung up on one approach,” even when it proved popular and profitable to do so.

“He was not only prolific, he was a unique composer,” said Phil Pastras, editor of Silver’s 2006 book, “Let’s Get to the Nitty Gritty: The Autobiography of Horace Silver.” “Even an ordinary 12-bar blues in his hands turned into something magical.”

Silver was born Sept. 2, 1928, in Norwalk, Conn. His father, John Tavares Silver, was an immigrant from Cape Verde, an island group off the west coast of Africa. Growing up Silver heard the folk music of his father’s homeland and black gospel music of his mother’s church. But it was listening to the Jimmie Lunceford band at a local amusement park when he was 11 years old that placed Silver squarely onto the path of music.

“When I heard that band play, I said to myself, ‘That’s for me. I want to be a musician,’ “ Silver wrote in his autobiography.

Silver began his study of music on an old upright piano that an uncle salvaged. By the time he was a teenager, Silver was playing scores and composing.

On occasion he ditched school and hopped a train to New York to indulge in the city’s music scene. He heard pianist Art Tatum play at the Downbeat Club and later wrote that it was “like watching and listening to a miracle in progress.”

Never shy about expressing his respect and admiration for other artists, Silver’s list of “piano inspirations” was long: Tatum, Thelonious Monk, Bud Powell, Teddy Wilson, Nat King Cole.

In composing works, Silver found inspiration from all around — nature, people, the events of his life. Listening to a cricket inspired the record “Philley Millie.” The whistle of a boiling kettle of water was the muse for “Serenade to a Tea Kettle.” Sometimes songs came from “just doodlin’ around on the piano.” But the source of other compositions was what Silver called “the spirit.”

In 1949 tenor saxophonist Stan Getz offered a 21-year-old Silver his first professional job as a sideman and a chance to play with top-ranked musicians. From the start Silver defined himself as a composer. In his time with Getz the group recorded three of his compositions: “Penny,” (1951) “Potter’s Luck,” and “Split Kick.”

After a year with Getz, Silver left and began freelancing, playing gigs with Coleman Hawkins, Lester “Prez” Young and Art Blakey. For recording sessions in 1954 and 1955 Silver brought together a quintet that included Art Blakey on drums, Hank Mobley on tenor sax, Kenny Dorham on trumpet and Doug Watkins on bass. The recording sessions produced two albums originally released as “The Horace Silver Quintet,” and gave birth to what would become the Jazz Messengers. Silver called them “most definitely one of the greatest groups I’ve ever had the privilege of recording with.”

During the 1950s and ’60s Silver produced a body of work that would years later earn him recognition as a founder of hard bop, generally described as music that draws on the rhythmic and harmonic principles of bebop but with heavy influences of gospel, blues and R&B.

Jazz historian Nat Hentoff described Silver’s music then as “soul jazz,” a reaction by Silver, Blakey and others to “West Coast Jazz,” which was being played by “white guys who were getting all the attention,” Hentoff said.

In reaction, some black musicians returned to their roots, the gospel music of the church. At an early rehearsal of the Jazz Messengers, some of the musicians said, “that’s one thing those white cats on the West Coast can’t copy,” Hentoff said in an interview. In 1955, the band had a hit with “The Preacher.”

For Silver, who cared little for the labels applied to describe music, what he and others were doing were simply “exploring, extending and developing the innovations of the previous generation.”

After a year and a half Silver left the Jazz Messengers and would eventually form another Horace Silver Quintet that included Mobley, trumpeter Art Farmer, bassist Doug Watkins and drummer Louis Hayes. Donald Byrd often subbed for Farmer.

The quintet produced the album “Six Pieces of Silver,” which included the hit “Señor Blues,” now a jazz standard, as well as the albums “Silver’s Blue” in 1956 and “Further Explanations” in 1958.

Silver was equally adept at spotting and introducing new talent. He made a point of encouraging young musicians and giving them an opportunity to develop with more experienced performers, said saxophonist Bennie Maupin, who played with Silver on the “Six Pieces of Silver” album.

Maupin, who had grown up listening to Silver’s music on the radio and jukeboxes, recalled him as “a real taskmaster.” Band members were required to memorize every piece of music the group played so that no music sheets were ever seen on stage, Maupin said. Maupin, who called Silver “Boss Man,” would go on to play with other bands, but retained the practice of memorizing the music.

While Maupin learned from his mentor, he also taught Silver about yoga, vegetarianism and metaphysics. By the 1970s Silver’s spiritual quest had found its way into his music. Always restless and eager to try something different, he explored different forms of instrumentation, such as the electric keyboard, and added vocal music, working extensively with singer Andy Bey.

A three-album set titled “The United States of Mind” was released in the early 1970s. The first album did not sell well and its lyrics were criticized as “preachy,” Pastras wrote. To complete the series Silver had to fight with Blue Note executives who wanted him to return to his previous works.

The music mesmerized vocalist DeeDee Bridgewater. Bridgewater was a 20-year-old new bride, married to Cecil Bridgewater, a trumpeter who was a member of Silver’s band in the early 1970s. Traveling with the group she heard the music nightly and longed to sing it, an honor that belonged only to Bey.

“I would sit in the back of the club,” Bridgewater said in an interview with the Los Angeles Times. “I just fell in love with his music. I thought his music was so hip and so modern and so advanced and so funky.”

In 1980, Silver formed his own label, Silveto, “that was dedicated to the spiritual, holistic, self-help elements in music — music with a spiritual principal,” he said in a 1993 Chicago Tribune interview.

“But there aren’t too many people interested in that — the world is still afraid of the spiritual side of jazz,” he said.

After Silveto he formed Emerald Records, for straight-ahead jazz, but that label failed to catch on.

Though he remained highly productive during those years of recording under his own label, much of his post-1970 music is difficult to find today, Pastras said. Critics also focus — wrongly, Pastras said — on his works of the ’50 and ’60s. The quality of the work on his independent labels rivals that of his earlier years, but simply went unnoticed, Pastras said.

“He never got away from the element of fun in his music,” said McBride, who in 2007 organized a tribute to Silver at Disney Hall. “In an art form where fun is sometimes perceived as not being serious, I think Horace proved otherwise with his music.”

Silver is survived by his son.

Stewart is a former Times staff writer.

More to Read

Start your day right

Sign up for Essential California for the L.A. Times biggest news, features and recommendations in your inbox six days a week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.