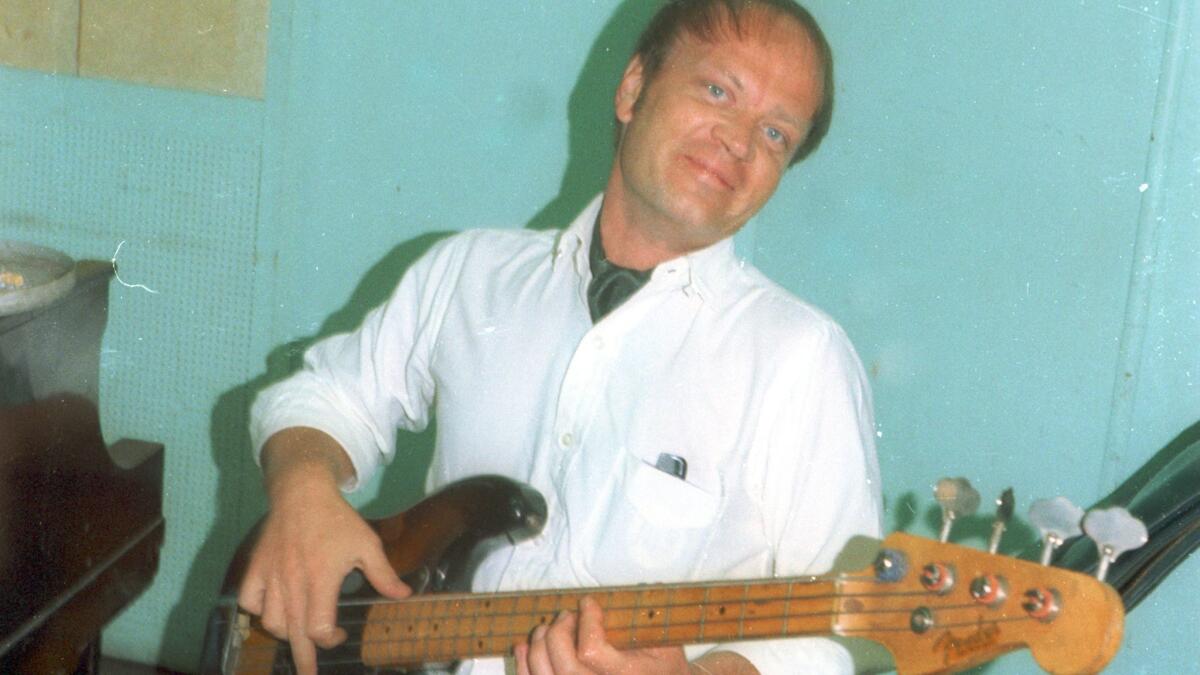

Lyle Ritz dies at 87; ‘Wrecking Crew’ bassist became Hawaii ukulele legend

- Share via

As he was laying down the bass riffs for Ray Charles, Tina Turner and the Beach Boys in the recording studios of L.A. — his music filling the soundtrack of the 1960s, a different musical reputation was growing 2,500 miles away.

But it wasn’t the bass guitar that had drawn Hawaiian musicians to Lyle Ritz. It was the ukulele.

Years before Ritz became a member of the fabled group of session musicians known as “the Wrecking Crew,” he had had a musical affair with the ukulele, recording several albums.

He wasn’t a fan of the traditional island melodies, but was intrigued at how he could coax jazz from an instrument that looked so small and powerless.

When he was later invited to perform at a ukulele festival in Honolulu, he discovered that while he’d been performing in near-anonymity in the studios, he was the stuff of legend in Hawaii. Ukulele players had been listening to his albums, imitating him, building on his music. When he finally arrived in the islands in the mid-’80s, a legion of fans awaited him.

Ritz, who became the standard bearer for ukulele jazz and expanded the versatility and possibilities of the instrument, died March 3 in Portland, Ore. He was 87 and had continued to — as he put it — “noodle” with the ukulele well into his 80s, even as age slowed his hands.

“I don’t play as many notes as I used to,” he told the Honolulu Star in 2002, “but they’re better ones.”

Born Jan. 10, 1930, in Cleveland, Ritz came west and attended Occidental College before transfering to USC, where he learned to play the tuba. He also put his hands on a ukulele for the first time when he got a part-time job at Southern California Music Co. in downtown L.A., where he was expected to demonstrate how to play the instrument for prospective customers.

“And one day somebody wanted to see this beautiful, nice big tenor uke,” Ritz told NPR in 2007. “I picked it up and played a few chords on it, and I was gone.”

During the Korean War he was drafted and assigned to band duty at Ft. Ord outside Monterey, learning to play the stand-up bass. When he came back to L.A. while on leave, he stopped by the music store and fiddled around on a ukulele, unaware that jazz guitarist Barney Kessel was in the shop.

The chance meeting led to a contract with Verve Records and eventually two albums, “How About Uke?” and “50th State Jazz.” Neither recording was a huge seller but their existence alone slowly paved the way for what would become ukulele jazz.

Roy Sakuma, a longtime ukulele teacher and founder of Hawaii’s annual ukulele festival in Waikiki, told NPR that as a youth, he would sit by the record player and listen to “How About Uke?” over and over again.

“All these fantastic chord harmonies that just, you know, took music to a whole new level on the ukulele.”

But at the time, the influence of his music had yet to unfold and he slowly lost interest in the instrument. The bass guitar paid better, and so did rock ‘n’ roll.

The Wrecking Crew was a prolific group of session musicians that provided muscle and distinction to an entire playlist of albums in the ’60s — the Beach Boys, the Byrds, Herb Alpert, and Sonny and Cher. That’s the Wrecking Crew on Simon and Garfunkel’s “Bridge Over Troubled Waters” and the Mamas & the Papas’ “California Dreamin.’” And that’s them on the Beach Boys’ “Good Vibrations.”

Brian Wilson, the voice, songwriter and architect of the Beach Boys’ influential catalog of songs, considered the Wrecking Crew to be his sonic muse.

“They inspired me to reach higher ground,” Wilson said in “Sound Explosion! Inside L.A.’s Studio Factory with the Wrecking Crew,” a 2016 book on the session musicians.

Some of the session musicians, like Glen Campbell, Leon Russell and Jack Nitzsche, found fame. Others remained practically anonymous, even while their music drifted from radios and record players across America. For Ritz, it brought him back to the ukulele.

In 1985, after years of session work and movie soundtracks, Ritz was invited to perform at the Ukulele Festival. Impressed that he’d unknowingly touched so many musicians, he moved his family to Oahu, where he continued to perform and record. in 2007, he was inducted into the Ukulele Hall of Fame.

“Anything you want, you can express on the uke,” he told Ukulele Magazine. “It’s an honest-to-goodness musical instrument, and it’ll do anything.”

Ritz is survived by his wife, Geri; a daughter, Emily Ritz Miyasato; a stepson, Thomas Ritz; and two granddaughters.

More to Read

Start your day right

Sign up for Essential California for the L.A. Times biggest news, features and recommendations in your inbox six days a week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.