Malcolm Boyd dies at 91; Episcopal priest took prayer to the streets

- Share via

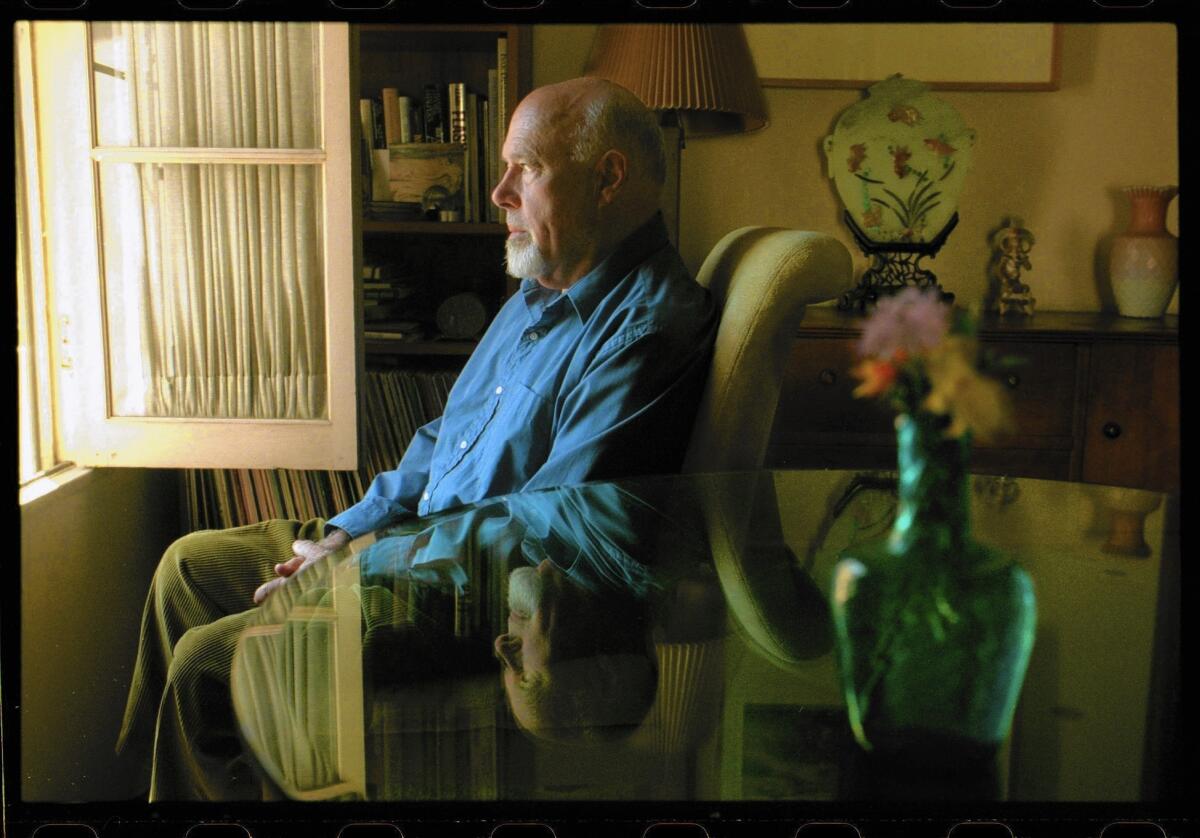

The Rev. Malcolm Boyd, the Episcopal priest whose book “Are You Running With Me, Jesus?” took prayer out of church onto the city streets in a slangy vernacular not found in Sunday missals, has died. He was 91.

Boyd died Friday under hospice care in Los Angeles from complications of pneumonia, according to Robert Williams, spokesman for the Episcopal Diocese of Los Angeles.

Boyd delivered riffs on life’s grittier problems — the white racists afraid of integration, or teenage girls who get pregnant — with a candor that was rarely heard from a priest leading a community at prayer.

He wrote more than two dozen books, many of them about people who did not fit the blue-sky ideal. But none of his prayers for them were as raw and urgent as those in the 1965 collection that sold half a million copies.

“‘Are You Running With Me, Jesus?’ is a classic of spiritual writing for its generation,” said the Rev. Robert Raines, a former director of the Kirkridge Retreat Center in Bangor, Pa. “It tells about the underbelly of society, which Malcolm knew something about. His was a Christian faith lived out in bars and on the streets. His prayers came out of the realization that God is not only in church. God is in the painful situations of your life,” Raines said in a 2004 interview with The Times.

“This girl got pregnant, Lord, and she isn’t married,” one prayer in the book begins. “There was this guy, you see, and she had a little too much to drink. It sounds so stupid, but the loneliness was real. Where were her parents in all this? It’s hard to know.”

Boyd’s flair for drama kept him in the spotlight from his earliest years as a clergyman. In the segregated South of 1961 he was among the first white ministers to work the voter registration drives. Later in the decade, when religious institutions were criticized as self-serving or irrelevant, he delivered his “prayer poems” from nightclub stages and at the Newport Jazz Festival with guitarist Charlie Byrd.

But he took his boldest step in 1976, when he announced that he was gay. At the time, most Christian churches condemned what they referred to as the homosexual lifestyle, which he was living.

Boyd followed his public statement with the book “Take off the Masks,” saying he wrote it because he was tired of living a lie.

One former admirer burned Boyd’s books. For years afterward, he had trouble finding work at a church. “It was wilderness time,” he said in a 2003 interview with the Indianapolis Star. “There was criticism, there was unemployability. I learned you have to be flexible in life.”

It was a lesson he struggled with repeatedly. “The single great war of my life has been against fragmentation and for wholeness, against labels and for identity,” he wrote in his 1969 memoir “As I Live and Breathe.”

After announcing his homosexuality, Boyd led consciousness-raising groups for gay people and wrote books about gay spirituality. In 1984, he helped organize one of the first Christian Masses for people with AIDS.

For all his pioneering ventures, it was Boyd’s bestselling book of prayer poems, which conveyed a close, personal knowledge of the messy world that struck a chord with the widest audience.

Boyd’s “genius,” South African Archbishop Desmond Tutu once said, was to illustrate the presence of God “even for those who say they do not believe in God.”

One prayer in the book begins with a walk through a Detroit slum.

“Look up at that window Lord, where the old guy is sitting,” Boyd wrote. “He just moved a short bit away from the window. Maybe he moved because he felt my eyes on him from the sidewalk down here. I didn’t mean to embarrass him, Lord; I just wanted to let him know somebody understands he’s alive and he’s your brother, so he’s not alone or lost. Does he know it, Jesus?”

Boyd’s flamboyant style was evident long before he became a priest. In his 20s he built a Hollywood publicity agency that specialized in promoting movies and radio shows. In 1949 he formed a radio and TV production company with his friends Charles “Buddy” Rogers and Mary Pickford.

The company was hardly a year old when Boyd disclosed his plan to be ordained an Episcopal priest — transformation marked by his show business friends with a farewell luncheon at Ciro’s, the old Hollywood haunt.

Boyd was born June 8, 1923, in Buffalo, N.Y., the only child of Melville Boyd, a wealthy financier, and Beatrice Lowrie Boyd. The stock market crash of 1929, followed by his parents’ divorce, changed his prospects. He and his mother moved to Colorado Springs, Colo., where she worked as a teacher and he buried himself in books.

Attending the University of Arizona, he came to uneasy terms with his homosexuality. “I dated girls but I longed for boys,’’ he wrote in a 1989 essay. “I had to learn to hide my feelings … and show a face that bore little resemblance to my real self.”

After graduation in 1944 he spent six years in Hollywood before he entered the Church Divinity School of the Pacific in Berkeley. He was ordained an Episcopal priest in 1955.

Controversy surrounded him from the start. At his first parish in Indianapolis the all-white membership was distressed when he invited an African American pastor to speak. As a chaplain at Colorado State University, he hosted poetry readings and group discussions in a coffee house. A newspaper dubbed him the “espresso priest” and wrote of his ‘’coffee house conversions.”

Criticized by the local bishop, Boyd resigned. He was next hired as a university chaplain at Wayne State University in Detroit, where he got involved in the desegregation movement and traveled often to the Deep South on voter registration drives.

In 1965, he was named writer in residence at Washington, D.C.’s Episcopal Church of the Atonement. He traveled, lectured and read his poetry on college campuses.

He and guitarist Byrd gave concerts, including one at the 1966 Newport Jazz Festival. Boyd read his work while Byrd improvised on the guitar.

That year Boyd also appeared at the “hungry i” nightclub in San Francisco. Some nights he warmed up the audience for Dick Gregory, the comedian and social activist. Every night, Boyd wore his clerical collar and told the audience that he was there as a priest not an entertainer.

Some of his monologues sounded like mini-sermons. “See him over there, Lord, driving the new blue car?” one of his prayer poems began. “He knows what he wants and how to get it. … But he feels awfully threatened, Jesus, by a lot of things and people. He doesn’t see why the world can’t remain secure, old-fashioned, Protestant and white. … He’s looking out his car window. Does he see you standing on the street, Jesus?”

Fame came crashing down in 1976 when Boyd announced that he was homosexual at an Episcopal convention in Chicago. For several years afterward he was turned down for staff positions at Episcopal churches. The Rev. Frederick Fenton, rector of St. Augustine-by-the-Sea in Santa Monica and a longtime friend, invited Boyd to join his staff in 1982.

“We lost some members but those who stayed loved Malcolm dearly,” Fenton said. “He was incredibly creative, compassionate, funny. And he burned at the ridiculing of any person. Like a human chameleon he absorbed hurt feelings and then showed the rest of us what it was like.”

While he was based at St. Augustine, Boyd was elected president of PEN, an advocacy group for writers’ freedom of speech. He started living with Mark Thompson, who was a senior editor for the Advocate, a national gay and lesbian newspaper. At the time, it was generally expected that gay Episcopal clergy remain celibate.

Twenty years later in 2004, when Boyd and Thompson renewed their vows in a church ceremony, the majority of Episcopalians had approved of gay marriage at a national conference. Boyd’s anniversary service was held at the Episcopal Cathedral Center of St. Paul in Los Angeles with five bishops among the guests and Bishop Jon Bruno presiding.

Boyd and Thompson married in July 2013, after Proposition 8 was overturned and same-sex unions resumed in California.

“Malcolm lives on in our hearts and minds through the wise words and courageous example he has shared with us through the years,” Bruno, bishop of the six-county diocese, said Friday in a statement. “We pray in thanksgiving for Malcolm’s life and ministry, for his tireless advocacy for civil rights, and for his faithful devotion to Jesus who now welcomes him to eternal life and comforts us in our sense of loss.”

In his later years, Boyd was writer-in-residence at the Cathedral Center of St. Paul. He also worked as a chaplain for AIDS patients and helped to establish a gay history archive at USC.

He continued to write. In a 2014 Huffington Post column, he asked, in his down-to-earth style, for a chat with Pope Francis about religious discrimination against gay people.

“Is this asking too much?” he wrote. “Pope Francis, are you on board?

“I’d like to spend a reflective evening with you, send out for a pizza from a great place near the Vatican, open a bottle of Chianti, put our feet up, relax, and share thoughts and aspirations.”

A celebration of Boyd’s life will be held at 2 p.m. on Saturday, March 21, at the Cathedral Center of St. Paul, 840 Echo Park Ave., Los Angeles.

Rourke is a former Times staff writer.

Times staff writer Steve Chawkins contributed to this report.

More to Read

Start your day right

Sign up for Essential California for the L.A. Times biggest news, features and recommendations in your inbox six days a week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.